If Acetone flew under your radar in the ’90s, you’ll have your work cut out for you with I’m Still Waiting., New West Records’ 11-LP boxed set covering the ill-fated Los Angeles trio’s seven-year studio output. Out now, the meticulously assembled package includes studio albums Cindy (1993), If You Only Knew (1995), Acetone (1997) and York Blvd. (2000), plus the group’s self-titled debut EP (1993), mini-LP I Guess I Would (1995) and a nine-track bonus LP.

Acetone newbies have a surplus of ragged brilliance to unpack, while longtime fans get eight previously unreleased tunes and a remastered back catalog, much of which was out of print. If You Only Knew is available for the first time on vinyl, and Acetone features the rare original mix favored by the band. Prime Cuts, a bonus LP of unreleased tracks, includes “Nobody Home,” a demo recorded in the spare-bedroom rehearsal space at bassist/vocalist Richie Lee’s Glendale, Calif., home circa 1998. We’re premiering the digital version below.

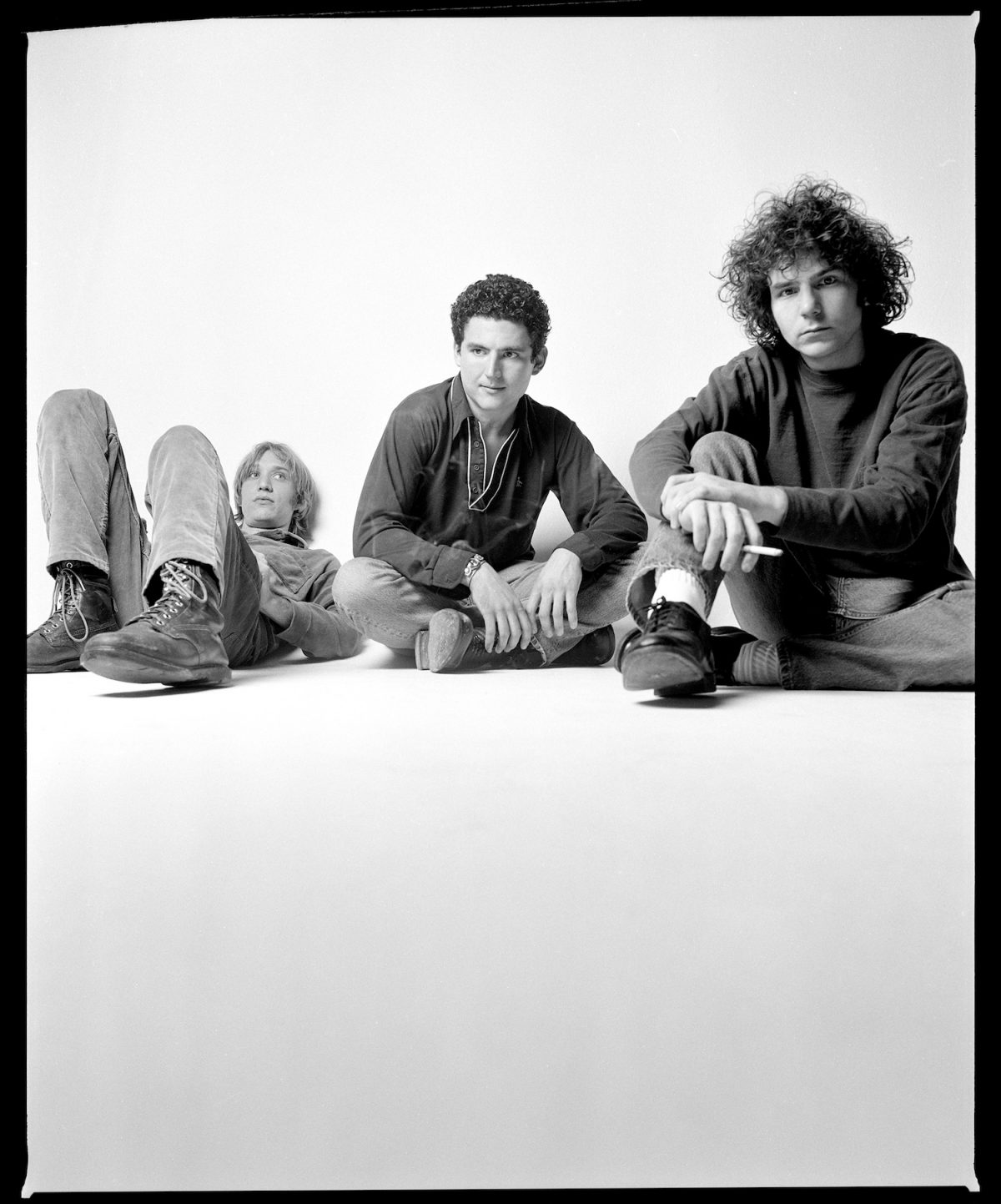

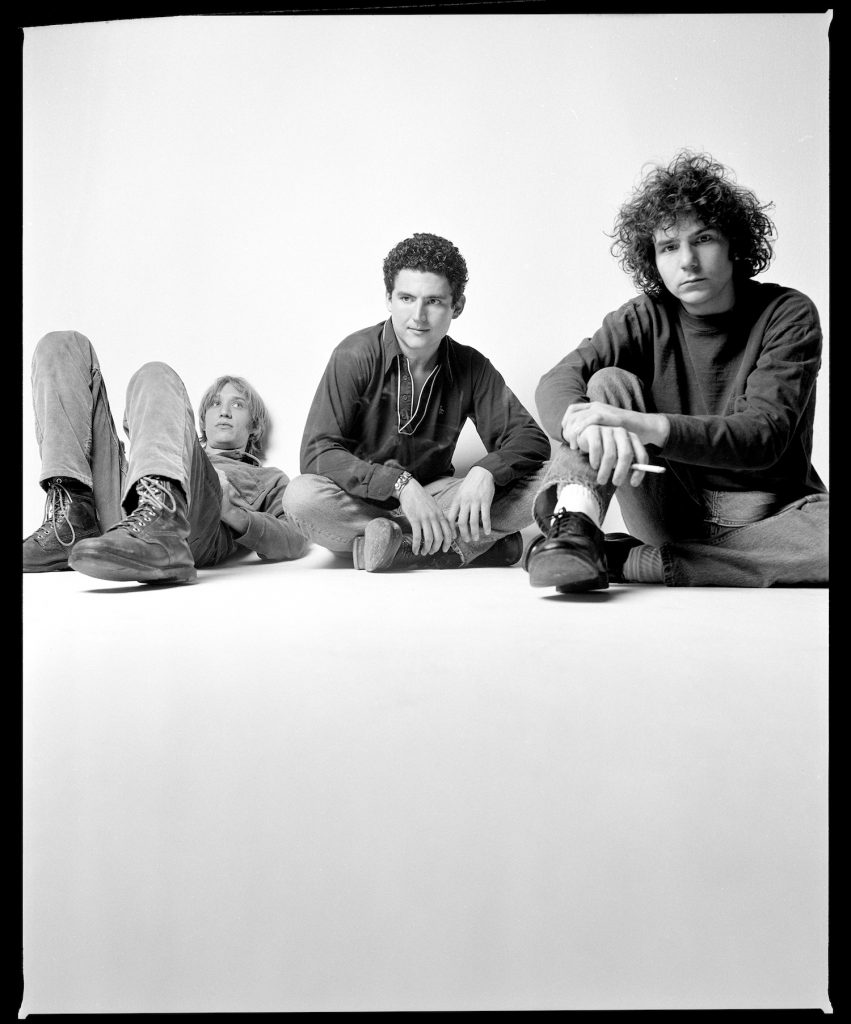

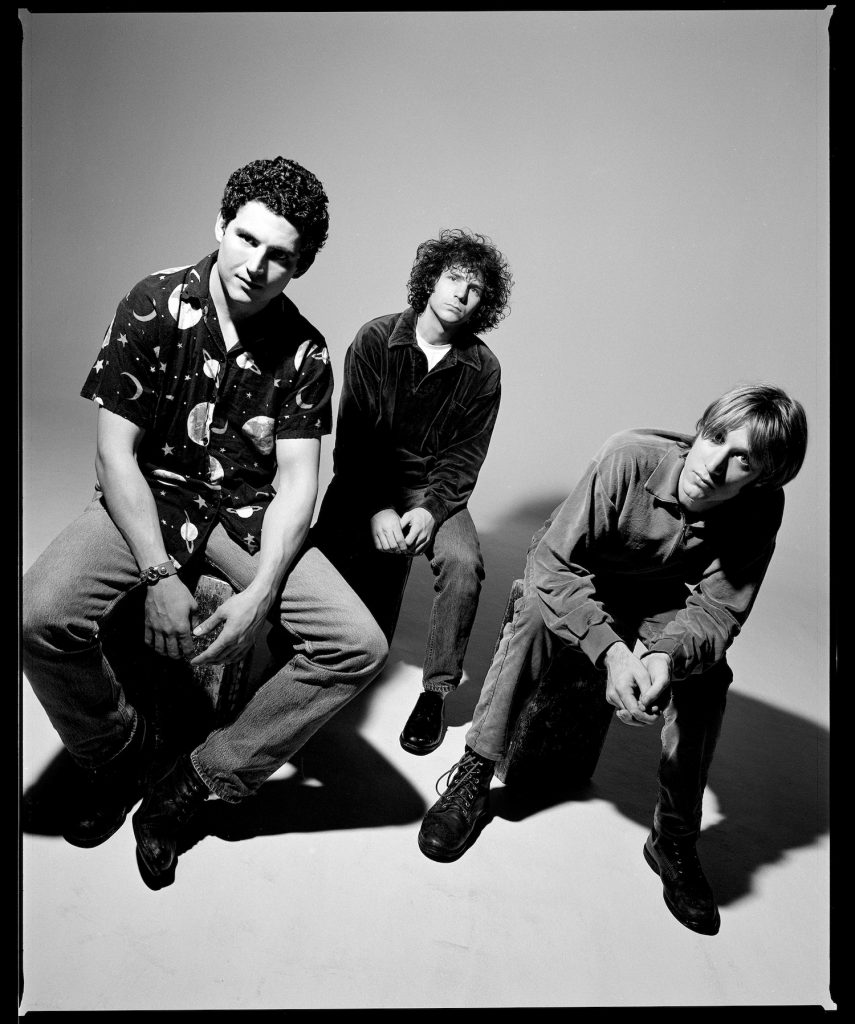

Given its power-trio configuration and the self-inflicted fate of Lee, Acetone is sometimes mentioned alongside Nirvana, though the two bands couldn’t have been more different in sound and approach. Lee, drummer Steve Hadley and guitarist/vocalist Mark Lightcap officially convened as Acetone in 1991, choosing as their unofficial headquarters Hadley’s rundown pool house in L.A.’s Highland Park neighborhood. Snapped up by Virgin Records subsidiary Vernon Yard in the post-Nevermind industry signing binge, Acetone released its eponymous EP and full-length Cindy in 1993. Strikingly unique yet superficially unassuming, Acetone’s relaxed sonics invite comparisons to Galaxie 500 and labelmate Low.

Indeed, the band’s primary touchstones were similar: the Velvet Underground, Brian Eno, Gram Parsons, Smile-era Brain Wilson and early Pink Floyd, among others. As Acetone evolved, the band continued to wander its own polarizing path, even as Acetone opened for bigger acts like Oasis, Mazzy Star, the Verve, Spiritualized and Garbage. Dropped by Vernon Yard, the trio found a new home for its final two albums on Neil Young’s Vapor Records. Tragically, after years of addiction issues, Lee ended his life in 2001. For more on the band’s story, check out the boxed set’s liner notes by Spiritualized’s Jason Pierce and Matmos’ Drew Daniel.

Three decades have passed since the September 1993 release of Cindy. For Lightcap, Acetone feels like a band frozen in time. On a Zoom call from his home in L.A., he offered his thoughts on all the renewed appreciation for the trio.

How did the box come about?

A lot of people had come around asking about Acetone reissues over the years. The real stumbling block was that those early records were so deeply ensconced in the Universal/EMI/Sony vault that it was virtually impossible to get someone to answer even an email about rereleasing anything. It’s just so small potatoes, and they’re such a giant company. I said to (New West Records’) Brady (Brock), “Others have tried and wound up in tears at the end of the day. But if you think you can make it happen, that would be amazing.”

Brady had the connections and the tenacity to go all the way and make it happen. The whole project just kept expanding. Originally, we thought it would just be one LP for each record. But from a fidelity standpoint, they were all too long to fit on one disc, so it went from six or seven discs to 11 discs. But New West just stuck with it, and I’m really amazed and grateful.

It was a crazy time in the music industry when Acetone got signed. How did you endure all the nonsense?

We were all about the music. We were going to do it regardless of whether we were selling records or not. Sure, we wanted to quit our day jobs, but we didn’t expect to be signed so quickly or in such a spectacular fashion.

How did that happen?

Our management sent out our demos, and it was perfectly timed for the post-Nirvana feeding frenzy. It seemed like almost overnight we had Geffen and Interscope and Vernon Yard barking up our tree. (Vernon Yard’s) Keith Wood was a real music fan. He loved the music, and he wanted to have it. But it was crazy. We hadn’t even played any gigs at that point.

There was a list of pretty much the same influences accompanying every Acetone write-up. If you had to pick one, what would it be?

To a kid growing up on the East Coast, I really loved the Meat Puppets. To this day, I think Meat Puppets II is one of greatest rock ’n’ roll albums ever. My urge to explore the extreme boundaries was partly the result of getting into the Meat Puppets at a formative age.

How would you chart Acetone’s early evolution?

We originally had this band Spinout, which was this punk-influenced rock band. Steve, Richie and I were getting bored with it, and whenever our singer wasn’t around, we’d go off into these more nuanced explorations. At a certain point, we decided to divorce ourselves from the singer and head off in that direction. What you hear on the EP and Cindy is us running the gamut. “Chills” and “Endless Summer” are loud and totally bitchin’. Then you go into the full-blown lilt of “Louise.” That was our comfort zone—these extremes. We were big fans of the Velvets and Neil Young and Zeppelin, who would all do the same thing. In the ’90s, there was this expectation of, “Pick a lane, and stay in it.” We were just like, “Fuck that. We don’t want any part of that. We’re just gonna do what we want.”

Where did the obsession with country music originate?

When we were touring off those early records, we’d drive around listening endlessly to these mix tapes I’d made of Charlie Rich, Roger Miller and whatnot. So that crept into our thinking about songwriting. On If You Only Knew, you have this combination of the country influence and a little Memphis soul creeping in. We were constantly trying to absorb influences and mulch them into what made sense in this harmony-singing, power-trio reality we were going for.

The other guys’ drug habits were getting bad, so If You Only Knew is not an up-tempo, peppy record. It’s almost like having a wet towel thrown on you. [Laughs] The band crashed after that. Drugs took their toll, and we got dropped by the label and wound up back at square one. We all went back to having to work for a living, but we kept writing songs.

Talk a bit about those last few years on Vapor.

At that point, our influences were more integrated into our approach, so there’s not the same kind of overt appropriation of riffs. It’s a much more organic approach to writing. We produced Acetone ourselves with our pal Scott (Campbell), who’d worked on the other records. We wanted to make this lush, natural-sounding record. It’s still got all these loose ends because it’s an Acetone record, but we also loved tight pop records. I’m a huge Bee Gees fan. And the Beach Boys.

With York Blvd., the label wanted us to work with a producer who could tighten it up and get something they could actually sell. We wanted that, too. They put us together with Eric Sarafin. He hadn’t done much producing, but he was a really accomplished engineer. That record sounds the tightest of the bunch, for sure. But there’s also an element our aesthetic that we couldn’t sustain. Putting pitch-correction on Richie’s voice really set off a crazy psychic meltdown on his part. Some of my favorite recordings are on that record, but then there’s also a lot of missed opportunities. The vexing thing is that it’s the last record. If we’d been able to incorporate what we’d learned making York Blvd. and brought it to the next record, that would’ve been an amazing thing.

How did you come to terms with what happened to Richie?

It was awful—it was just devastating. And with a suicide, it’s harder to grieve because there’s all this anger intermingled with it. I had a whole record of solo material, some which was supposed to be Acetone songs. I eventually got back to work on that and began playing with other people; I was doing a lot of work with Matmos. Steve didn’t have other projects going on. He didn’t have a stable relationship at that point, and he was still trying to get on top of his drug habit. He and Richie were intertwined in the heroin world in a way Richie and I weren’t—there was another layer of complexity for him. Those guys just went all in on that trip. They also made pretty sorry poster boys for the joys of being strung out on heroin. They didn’t make it look fun.

For me, there was a kind of survivor’s guilt. I had these recordings that were more in the Acetone realm. I shopped them around a bit, but it felt kind of weird to me. I realized it was wrong to be out there aggressively trying to move on in that way. And Acetone was poison at that point. We had our cult following, our handful of true believers. But it was not a thing.

If Richie had lived, do you think Acetone would’ve made another album?

Absolutely—and that’s one of those things that’s so frustrating to me. There’d been a lot of ego conflicts between he and I. It was never in the form of hot flashes—it was more like a cold war. But after the humbling experience of the later years, we were moving past that. I was really looking forward to the next record.

—Hobart Rowland