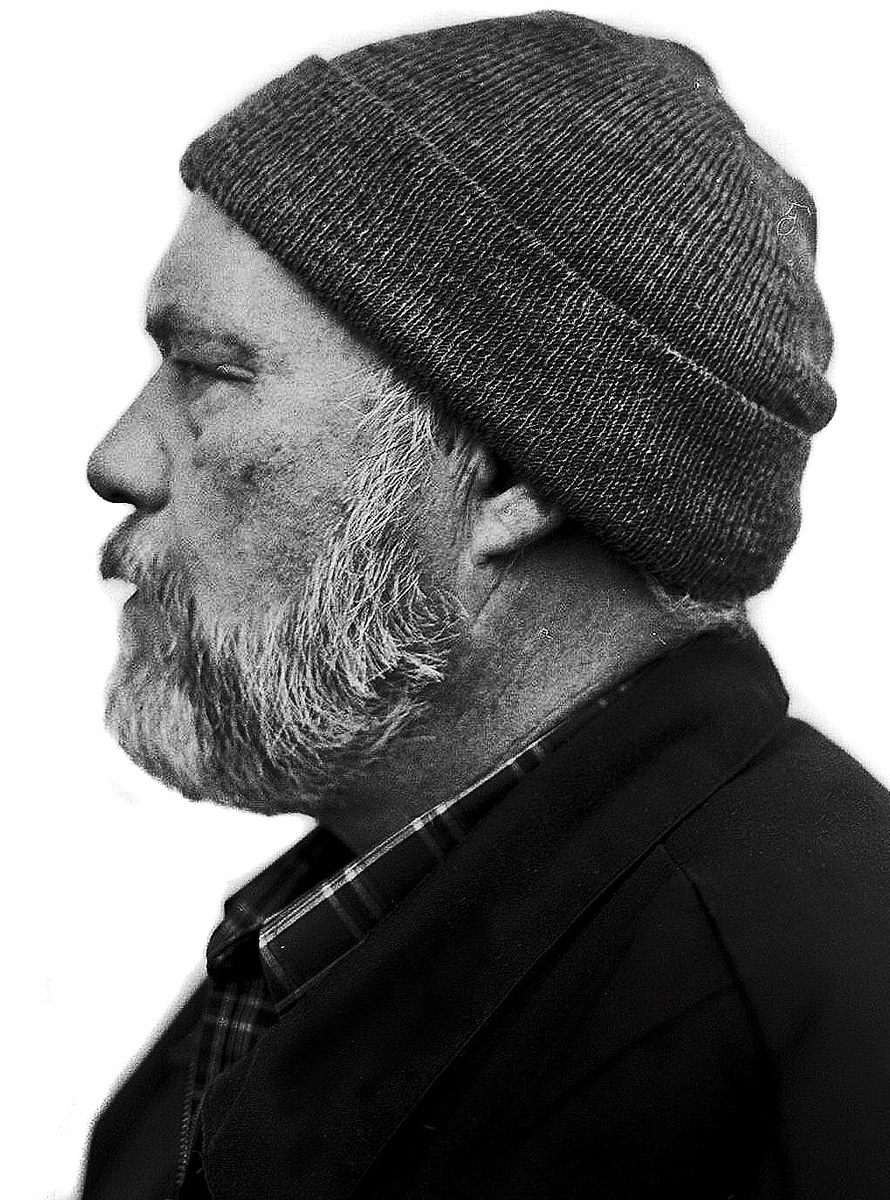

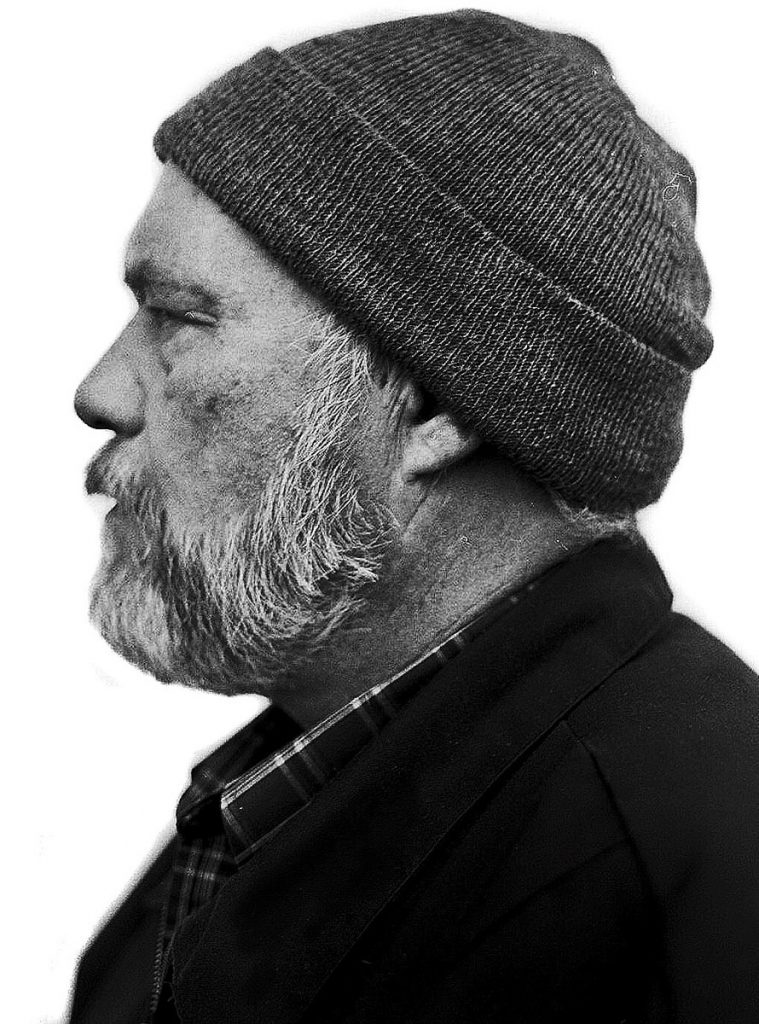

The last time we caught up with Jon Dee Graham, he was struggling to strike a balance between making a living as a traveling musician and being a good father to his young son. A quarter-century later, that son is a thriving adult living in New York City, and Graham has been dealing with the far weightier issues that come with aging. A native Texan and a fixture in Austin for decades now, the 64-year-old guitarist and singer/songwriter has survived a heart attack and a stroke over the past four years.

The heart attack occurred after a 2019 show on a particularly steamy July 4 night in Chicago. It took the paddles to bring him back. Hence the title of his first LP in seven years, Only Dead For A Little While (Strolling Bones). Hard-rocking, soulful and—like every Graham solo album—dominated by his gruff, take-it-or-leave-it vocals, Only Dead is a defiantly vibrant and life-affirming affair from a guy who’s stared death in the face more than once and never flinched.

Thanks to his acclaimed work as a solo artist and his influential ’80s stints with the Skunks and True Believers, Graham is a three-time inductee into the Austin Music Hall Of Fame. As a guitarist, he’s backed John Doe, True Believers alum Alejandro Escovedo and many others. These days, when he’s not on the road, he performs regularly at Austin’s Continental Club with a crack backup band that includes Andrew Duplantis (Son Volt) and drummer Joey Shuffield (Fastball). Graham was in an especially reflective mood when we reached him one afternoon as he was soaking up some nature at a friend’s house outside Austin.

It’s been particularly trying time for you of late. You’ve had two brushes with death in the last four years—and then there was the car accident in 2007.

I was in the hospital almost three weeks after that accident. I punctured my spleen and had it removed. I punctured a lung, scratched my liver, fractured both kneecaps. My joke is, well, I’ve proven I’m really hard to kill … I can be killed, but I won’t stay dead long. After the car accident—and, to a far greater extent, the death experience in Chicago—I get these people asking me, “So surely you must’ve come back with a greater appreciation for life.” And I say, “Hey, you know what? Absolutely. I’ll give you that—that much is true.” However, I also came back from it with a deep, personal, profound realization that the worst stuff you can imagine can happen to you just like that. I got a rap early on for being a downer, and the thing is, not if you really listen to my music. There’s a golden thread of hope that runs through every single song.

Maybe some of the heaviness people take away from your music has to do with your vocal delivery and not necessarily the content.

I’ve been touring this country and others in big wide circles for decades. This sounds so corny—fields and fields of Iowa corn—but the truth is that I don’t have fans so much as I have friends.

So that’s another way of saying your singing is an acquired taste?

[Laughs] To a certain degree, you’re right. I can’t help how I sing. It’s just how I sing. But I have so much to be grateful for. For a chubby farm boy who grew up on the (Texas) border, where Spanish was my second language, I’m so lucky. I’ve gotten to see so much, and I’ve gotten to do so much. If I was maybe three or four years younger, I probably wouldn’t have gotten to do any of it. I mean, who gets a record deal at 64? And the point isn’t, “Hey, Grampy gets to make one more record before he dies.”

So how does a chubby farm boy from a Texas border town become an acclaimed singer/songwriter with a record deal at 64?

One of the reasons is a teacher I had my freshman year in high school. I grew up between Eagle Pass and Del Rio, and I was one of five white guys in my class. Mrs. Molina is one the reason I write the way I write. It’s that period when your artistic bubble is swelling and rising. That’s when the lifelong damage happens.

Is Only Dead For A Little While your most joyful record?

I did a phoner yesterday, and the guy asked me, “Would it be safe to say that this is the record where you’re telling us not to be afraid of dying?” That was not my intention, but that’s it. When it comes to death, “By The Fire” is the closest glimpse of what I expect to happen when we die. We’re in the freezing wilderness, we see a glow off in the distance, and we keep walking toward it. We get there, and all our friends are there—all who’ve gone before.

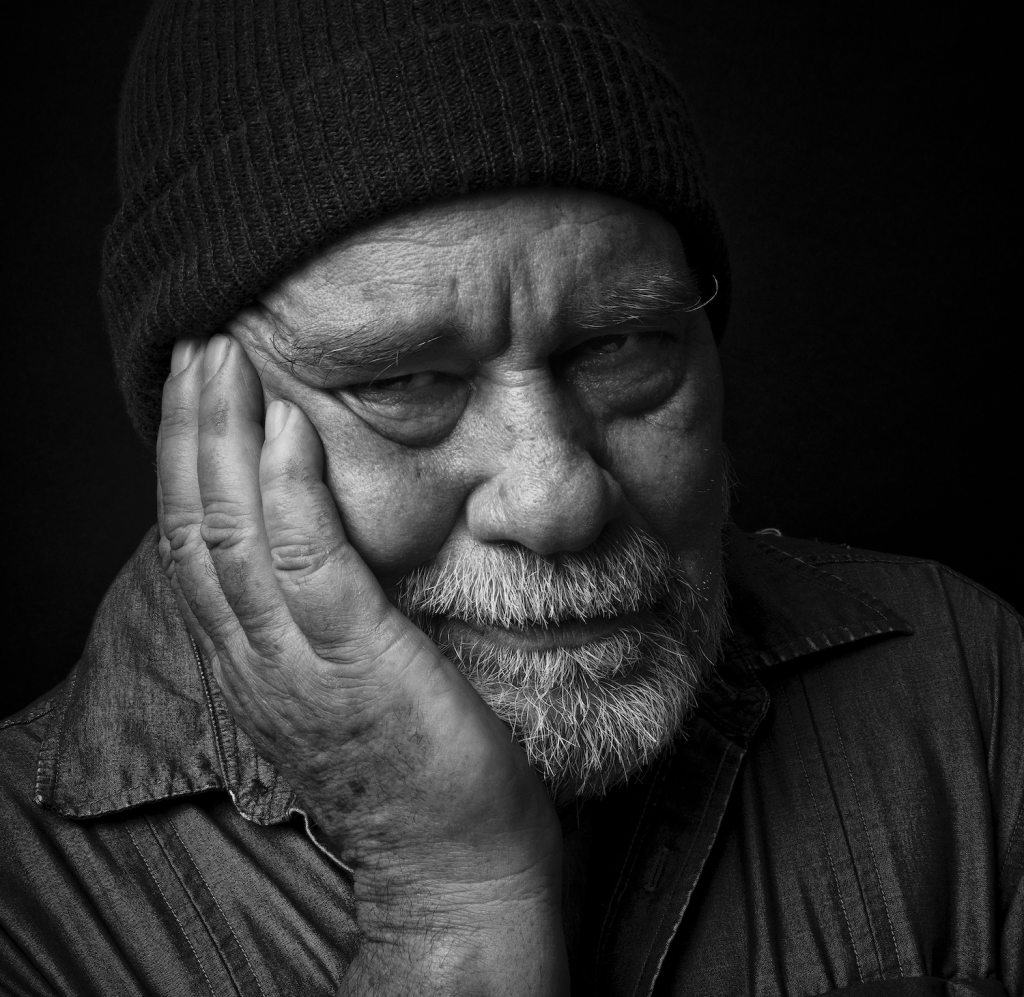

As someone who’s been there, what’s your take on near-death experiences?

Every single person I talk to wants a sign. I wish to hell I could say there was this flash of light and my grandmother was standing there with my favorite dog, Fluffy. I was only dead five to seven minutes, so maybe it takes a while to get to that. Or, even more possibly, because I do what I do, they said, “Nah. We’re not giving you anything inspiring to take back about the afterlife. You just go back and keep doing your job.”

Has the experience made you more spiritual?

I lost my dad when I was 17. My mom died when I turned 31. She never got to meet her grandkids. You can’t live as long as I have—and paid attention to what was going on around you—and not know deep in your heart that there’s something at work in the world. I’m not talking about a white-bearded, white-robed, sandaled czar of the heavens. I’m talking about something way bigger than that—and way more confusing than that. Stuff happens, and I go, “This is the worst thing that could’ve possibly happened. … Wait … It’s actually turning to my advantage.” Yes, tons of bad things happen. And yet, right now, I’m sitting on the back deck at my friend’s house watching a lemon-yellow butterfly hop from flower to flower. It’s like, “I’m sorry, could I have created that?”

—Hobart Rowland