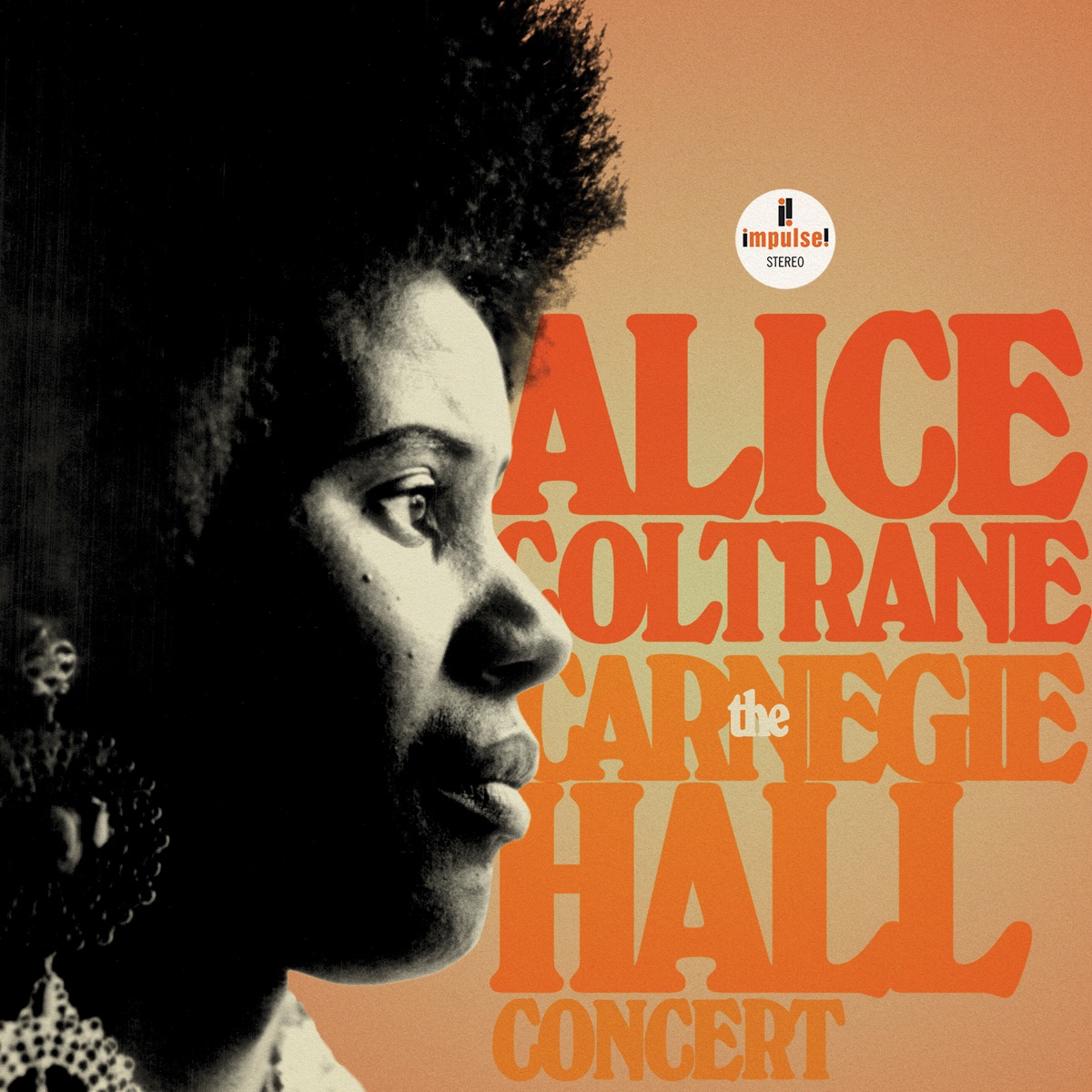

The Carnegie Hall Concert inaugurates The Year Of Alice, a series of concerts, exhibits and publications celebrating the legacy of musician, composer and spiritual eminence Alice Coltrane. The event does not line up neatly with any particular anniversary. Coltrane, who was also known as Swamini Turiyasangitananda, was born in 1937 and died in 2007, and the concert recording under consideration took place in 1971. But the timing acknowledges the enduring interest in her life’s work and the growing recognition of the singularity of her music.

1971 was a good year for Coltrane. She had come out of a time of profound grief following the deaths of both her husband, saxophonist John Coltrane, and her brother, bassist Ernie Farrow. Her association with guru Swami Satchidananda had helped her to attain a state of personal clarity and business stability, and her music was progressing from strength to strength as she added the concert harp to her piano playing and honed her skills as a composer whose aspirations increasingly reached beyond jazz.

In February of that year, Coltrane, along with singer Laura Nyro and rock band the Rascals (both followers of Satchidananda), held a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall for their teacher’s Integral Yoga Institute. For the occasion, Coltrane assembled an ensemble whose stylistic background and doubled instrumentation enabled her to express the breadth of her musical conception. Backing her was the double jazz trio of bassists Jimmy Garrison and Cecil McBee, drummers Ed Blackwell and Clifford Jarvis and saxophonists Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders. (Sanders also played flutes.) Also on hand were Kumar Kramer and Tulsi, on harmonium and tambura, respectively, which provided a grounding drone similar to that heard in Indian classical music.

Producer Ed Michel relates in the album’s voluminous liner notes a series of challenges, including surly stagehands and a microphone shortage, that affected the recording. The sound is consequently a tad distant, with the drone instruments underrepresented in the mix. If the album had been completed at the time, there might have been an effort made to fix their faintness with overdubs, but instead, the record company filed the tapes away, where they spent the next half century awaiting a legitimate release. Their appearance now continues a practice of Impulse! issuing of overlooked sessions that include John Coltrane’s Blue World and Both Directions At Once.

The music on The Carnegie Hall Concert, however, easily rises above the minor sonic blemishes. The double album (both CD and LP are so split, although the entire performance lasts 78 minutes) is divided into two of Alice’s compositions (on which she plays harp) and two more that were originally composed by John. “Journey In Satchidananda” reveals the merits of the doubled instrumentation. The basses don’t just provide a vamp, they exert a complex presence that draws the listener into a reflective state. On “Shiva-Loka,” the drums keep up a varied, percolating rhythm. Sailing over these foundations, Sanders’ overblown flute and Shepp’s yearning soprano sax take turns weaving through the stately, billowing harp on “Journey In Satchidananda,” establishing a vibe that’s both bluesy and meditative. The harp is even more of a balm on “Shiva-Loka,” its iridescent patterns balancing the soprano saxophone’s yearning tones.

The performances on the second disc conjure the supernova energies that the Coltranes had unleashed back in the mid-1960s. “Africa” is epic, with wave upon wave of percussion crashing against Alice’s stalwart piano and the sequential roaring of the two tenor saxophonists. “Leo” is even more intense. Instead of string solos, it erupts with an ensemble explosion of layered, monumental sound. Then the saxophonists desist, and Alice’s piano achieves escape velocity, tracing fiery streaks across the rhythmic firmament. Not only does this music recall what John and Alice were doing between 1965 and 1967, it equals it. [Impulse!]

—Bill Meyer