Chased and cornered by his demons six years ago, Steve Earle is now almost impossible to pin down, MAGNET hits the road with the songwriter, label owner, political activist and literary hopeful. By Robert Baird

“You don’t like chocolate?” Steve Earle exclaims with genuine astonishment at Elisa Sanders, the label manager of his E-Squared Records. “Well, that’s like not liking fucking!”

It’s five minutes before Earle and his band, the Dukes, go onstage at The Belly Up in Solana Beach, Calif. Even though everyone in the group is a hardened road veteran—none more so than Earle—and this isn’t the biggest show the band will play on this tour, there’s still a touch of backstage jitters. The mention of the f-word triggers Earle’s legendary iconoclastic wit.

“You know,” he says, “Church Of Christ people never fuck standing up because they’re afraid someone might look in the window and think they’re dancing.”

As everyone doubles over with laughter, bassist Kelly Looney—who, with 12 years of service under his belt, is the senior Duke—moves to the food table and takes a swig of Gatorade. “You know, Gatorade tastes like boogers,” Looney says with mock seriousness. Inspired by a fresh wave of laughter, he continues. “And the best part of the gig was the boogers.”

Ah, backstage with Steve Earle: clean and sober, yes, but still a good time. Good times are, in fact, a major theme in Earle’s life these days, though you’ll have to excuse the man if he doesn’t pause to genuflect on the matter. He’s simply too busy making up for lost time.

To understand exactly where that time was lost, you have to go back to the mid-’90s, when Earle’s indulgences weren’t just of the chocolate-and-sex variety. Back then, fun equaled drugs, and Earle had a lot of fun—mostly heroin, but also crack cocaine and just about any other substance preceded by the adjective “controlled.” In hindsight, it’s almost as if Earle wanted to see how many music-business bridges he could burn, how many marriages he could ruin, how many guitars he could pawn to get money for smack, how many times he could get busted before being convicted.

Since his release from jail six years ago, Earle’s passion-play life reads like a resurrection, both personal and artistic. He’s kicked his addictions, and critics choke on their own superlatives when describing Earle’s recent string of albums.

The Earle songbook has bulked up to more than 200 compositions, its pages dog-eared by admiring country artists like Emmylou Harris, Willie Nelson and Billy Ray Cyrus. That rock acts such as the Supersuckers, Pretenders and Brian Setzer have also paid tribute via cover versions speaks to the fact that Earle’s songwriting—earthy and tender, luminously poetic and unflinchingly honest—reaches across genre bounds. Earle is even the subject of a lyric on “Acoustic Guitar,” a Magnetic Fields tune from last year’s 69 Love Songs (“Acoustic guitar, if you think I play hard/Well, you could have belonged to Steve Earle”).

Once the insurrectionist who relentlessly and inventively dissed The Business (“Promoting pop music ain’t about nothing but whores and blow,” he told me last year), Earle is now a label owner, producer and keen-eared A&R man. The Twangtrust, his recording partnership with engineer Ray Kennedy, has produced records by Lucinda Williams, Ron Sexsmith, Cheri Knight, 6 String Drag, the V-Roys, Jack Ingram and others. Most of these albums have been issued by E-Squared, the label Earle formed to release his own music.

Through it all, Earle has also remained committed to social activism. Whether campaigning for the abolition of the death penalty and calling for an international moratorium on landmines or working to save the nation’s family farmers from extinction and shining a light on the national shame of homelessness, he has consistently given his time and energy to righteous causes. Though he’s still cranky, raffish and, at times, possessed of a rock star’s ego, Earle is as happy as he’s been in a long time.

Happiness, of course, can be a risky place for a songwriter to venture; pain makes for better songs. Earle’s newfound contentment (not to worry, on most people’s scale, he’s still a restless soul) comes from several directions. At home in Nashville, he and girlfriend Sara Sharpe (the couple met last year through their mutual involvement in the Tennessee Coalition Against State Killing) seem to have found some measure of peace, although with Earle’s history—six divorces, two with the same woman—that could always change.

Musically, the Dukes have never sounded so good. With Looney on bass, veteran alt-country producer Eric “Roscoe” Ambel (ex-Del-Lords) on guitar and Will Rigby (ex-dB’s) on drums, the Dukes—whose previous lineups were, at times, more rough than ready—are now capable of embracing pop, rock, country, folk and more with enthusiasm and experience.

Along with the domestic, band and label changes comes a shift in Earle’s songwriting to a more sophisticated, many-shades-of-gray approach, one that’s as influenced by the harmonic textures of the Beatles and the lyrical impressionism of Bob Dylan as it is rooted in the seminal twang of Gram Parsons and the bar-band crunch of the Replacements. The title track of Earle’s latest album, Transcendental Blues, kicks off with a Revolver-esque tabla intro and fuzz-guitar raga; a forlorn cello moans beneath the mournful regret of “The Boy Who Never Cried”; the trippy guitars on “Everyone’s In Love With You” buzz like sitars. In fact, a copy of Revolver rested on the studio console during the recording of Transcendental Blues. It was kept there as both bible and instruction manual.

“A lot of people don’t get it,” says Earle of his new album. “I think there’s a perception by some people that these songs aren’t as well-written as songs I’ve written in the past, simply because they tend to be more emotion-driven and relationship-driven and less narrative. But the truth is that the songs on this record were harder for me to write and, I think, harder for anybody to write and write well. My favorite song on [Transcendental Blues]—and it might be the song I’m proudest of as a writer in my entire career—is ‘The Boy Who Never Cried.’”

Often pigeonholed as a good ol’ boy and consigned to the roots-rock ghetto, Earle has always had a musical imagination that’s stretched far beyond the Nashville city limits. “[Steve could always go] from a blues/rock thing to a more pop kind of thing to a bluegrass thing to an Irish ballad or upbeat thing,” says Looney, the Duke most fit to judge the arc of Earle’s career. “But he’s really honed—not redefined but honed—his takes on the different kinds of music he’s always dabbled in.”

Despite Transcendental Blues’ bold eclecticism, radio seems to like the new Earle. The record made it to number five on the Billboard country chart—a chart that, except for his 1999 bluegrass album, The Mountain, has ignored Earle since 1988’s Copperhead Road. (For comparison’s sake, his debut, 1986’s Guitar Town, topped the chart.) Transcendental Blues also went to number one on both the Billboard Top Independent Albums chart and Gavin’s Americana chart.

“The next single, ‘I Can Wait,’ is going to adult-contemporary (radio),” says Earle. “It’s a chick song, which I’m totally down with. This record has got a lot more chick songs on it, which means my audiences aren’t as ugly and hairy as they’ve been. ‘Hey man, play that “Rattlesnake Road,”’” he bellows, imitating a drunken doofus. “I’m kinda sick of that shit.”

Stephen Fain Earle’s birth on Jan. 17, 1955, in Ft. Monroe, Va., was something of an accident: He was supposed to be born a Texan. To compensate for this embarrassing circumstance, Earle’s grandfather shipped a tobacco can of Texas soil to Virginia so that the first earth beneath his grandson’s feet would be genuine Texas terra firma. Earle grew up restless and errant near San Antonio in Schertz, Texas; he first tried heroin at age 14, around the time he dropped out of school. After some rambling, he wound up in Houston, living with his 19-year-old uncle. He supported himself working with his hands—framing houses, manning oil rigs, toiling on shrimp boats. He befriended songwriter Townes Van Zandt, whom Earle has often referred to as “a real good teacher and a real bad role model.” Nevertheless, the hard-drinking Van Zandt inspired Earle to earn his keep with a guitar.

Earle arrived in Nashville in 1975 and set about scratching out a patch of turf in a crowded field of aspiring songwriters. After only a few months of playing any club that would have him, Earle got his first break: Elvis Presley wanted to record Earle’s “Mustang Wine.” Unfortunately, the King never showed up for the session. (In a reversal of the old “Blue Suede Shoes” debacle, Carl Perkins later recorded the song.) Van Zandt introduced Earle to fellow Texas troubadour Guy Clark, who asked the 20-year-old to play bass and sing on his classic Old No. 1. Earle procured steady work over the next few years, playing bass in Clark’s band and working as a staff songwriter at RCA subsidiary Sunbury Dunbar.

In 1982, after singer Johnny Lee had a minor hit with the Earle-penned “When You Fall In Love,” Earle was signed by LSI Records and began recording as a solo artist. His debut release, the Pink And Black EP, caught the attention of Epic Records, which offered him a deal. More rockabilly than country, Earle’s gritty music rubbed against the grain of the slick product emanating from Nashville at the time; after several more recording sessions failed to generate any momentum, Epic dropped him in 1984. Soon thereafter, Earle met former Elvis piano player/producer Tony Brown, who got him signed to MCA Records in 1985.

The collective eyebrow of Music Row was raised with the 1986 release of Earle’s first LP, Guitar Town: A wild-assed kid from Texas blew into Nashville and, with one knockout punch of an album, changed country music forever. Arguably the most influential country/rock record since Gram Parsons’ pair of solo albums from more than a decade earlier, Guitar Town remains the cornerstone of Earle’s career and, in some ways, a milestone he may never equal. Four more classic albums for MCA followed, including 1988’s commercial breakthrough, Copperhead Road.

An unruly, eclectic, hard-rocking record with elements of bluegrass and Irish drinking music, Copperhead Road even featured guest musicians like the Pogues. MCA didn’t know how to sell a kick-ass rock album, not to mention a country wolf in rock’s clothing—Earle had recently been named one of the 10 sexiest men in country music by Playgirl—to country audiences. While the LP was successful in introducing Earle to rock radio, further raising expectations that he could achieve the level of fame of Bruce Springsteen or John Mellencamp, Copperhead Road’s raucous sound alienated the country-music community, along with his old fans and, ultimately, his record label. To Earle, it felt like “a war.”

“The thing you have to remember about Copperhead Road is that it didn’t sell as many records as most people think it did,” says Earle. “It was just certified gold six months ago.” Still, he’s convinced the album performed better than the label claims. “I never received a single dime in royalties from MCA,” says Earle. “Not a dime. I’ve been off the label for 10 years, and I haven’t received one single check.”

It was during his MCA years that Earle earned his reputation as a brilliant bad-ass with talent to burn and the recklessness to do just that. He was dressing the part in a leather jacket and sporting long hair, a look that wasn’t exactly making him friends and influencing people in Music City. Suffice it to say, they didn’t exactly love it over at the Grand Ole Opry. The cops weren’t too impressed with Mr. Rock Star, either, locking him up time and time again for drug possession and assault.

“Steve had too much cash from Copperhead Road,” says longtime Earle manager Dan Gillis. “Then, (1990’s) The Hard Way stiffed, and the whole thing about him being the ‘next Springsteen’ was going down the drain. The pressure just collapsed on him.”

By their very nature, rock ‘n’ roll drug tales are ripe for exaggeration, and Earle’s legend of the needle and the damage done is no exception. Most accounts err on the side of drama over what actually happened, with a recent New Yorker profile referring to Earle’s time in “prison.” He refuses to allow the black hole of his past to suck time and energy from his present life. After six hard-earned years of sobriety, the last thing Earle wants to talk about is drugs. He and the Dukes have a tacit agreement: If anyone is going to dredge up stories from those days, it damn well better be Earle who broaches the subject first. Although Looney and Gillis will later reel off a number of stories they ask me not to print, the official version comes from Earle himself.

“I got arrested with a tenth of a gram of heroin,” he says. “There’s almost no heroin in Nashville, but there happened to be some around—and it wasn’t very good—and a guy gave me some of it. I got stopped on my way out of the neighborhood; another block, and I would have been on the interstate. But I got pulled over. I didn’t have a driver’s license, so they could search my car right there. They found a rig and a tenth of a gram of heroin. The cop knew me, and he let me go. He gave me a ticket, because it was a misdemeanor. He could do that; it was his option. He just issued a ticket, so I had a court date. I showed up, I pled guilty and the judge set a hearing for sentencing to be 30 days later. I left that day—the day I pled guilty—and got arrested that afternoon for possession of crack and paraphernalia. So from that point on, I knew I was going to get hammered.”

Despite the high-profile arrests and generally bleak times, Earle always managed to keep his drug hell behind closed doors.

“I never noticed that the dark days were that dark, because there was still a continuity going on there,” says Looney. “He still went out and did his shows, and I always thought he did them well.”

In 1994, Earle was sentenced to 11 months and 29 days. All told, he ended up serving three months, both in jail (not prison) and treatment centers. “I didn’t really want to go to treatment,” says Earle. “But I was willing to go to treatment rather than jail because I thought I could walk out of there alive. I did really well in treatment, things really changed for me and turned around there, and I started really wanting to live. It happened in stages—it didn’t happen like a bolt out of the blue. At first, I thought, ‘I can get through this and get out.’ But then it started to be, ‘Well, I don’t ever want to go through this again.’”

After the Solana Beach show ends, we climb aboard the bus and settle in for the long ride to Los Angeles. Burritos are served, and drummer Rigby and I settle in to watch Sabrina, a 1954 movie starring Audrey Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart, on the satellite TV. So much for sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.

Although he’s played with Matthew Sweet and Freedy Johnston, Rigby is best known as the drummer for the dB’s, the seminal power-pop outfit that’s retained its critics’-darling status more than a decade after its demise. Rigby is flattered and also a little amused by the reverence with which the dB’s are still treated. “Rock critics love the dB’s,” he says. “But we broke up 12 years ago. We broke up before Copperhead Road came out, to put it in Steve Earle terms.”

I give him the look—one he must have seen hundreds of times, because he reads the question in my eyes. “Steve has said a couple of times, ‘If you make another dB’s record, I’ll put it out so fast it will make your head spin,’” he says. “But that and getting us all in the same room together is a whole different thing. Peter (Holsapple) has never expressed much interest in it. Gene (Holder) would do it, but only if we went to his recording studio so he didn’t have to leave his house. Every year or two, Chris (Stamey), on the other hand, says, ‘Why don’t we get together and do something?’ [A reunion] isn’t out of the realm of possibility.”

Rigby turns back to the TV screen and marvels at Hepburn’s lithe figure. “Man, look at that waist,” he muses as we both fall asleep, beers in hand.

We arrive at the hotel in L.A. in the wee hours of the morning. Earle shuffles off to bed with a stern warning to those who might attempt to wake him early. Tonight, the band is playing a high-profile gig before a crowd of music-industry types at the House Of Blues, and the afternoon is consumed by a longer-than-usual soundcheck that doubles as a five-song set performed in front of an audience of contest winners. The House Of Blues makes a point of letting the Dukes know just who is holding the leash; even Earle has to wear a backstage pass from the club, as it won’t honor his own tour laminate. This really gets his goat. Both band and crew take to calling the place the “House Of Rules”—and Earle never met a rule that wasn’t made for breaking.

Once onstage, however, Earle eases into the set, finally breaking into a smile about halfway through. Although the L.A. crowd is more sedate than the one last night, the Dukes give back twice as much energy as they’re getting from the audience, drawing on the sweaty telepathy that marks all great live bands. When Earle brings out Sheryl Crow to sing a duet on “Time Has Come Today,” the Chambers Brothers tune the pair recorded for the soundtrack to the Abbie Hoffman biopic Steal This Movie, the crowd explodes in hoots and hollers. Earle encores with a lovingly twanged-out reading of the Beatles’ “No Reply,” and then the band lays down a blistering rendition of Nirvana’s “Breed” (a song included on a bonus EP sold with early copies of Transcendental Blues) that leaves skid marks on the stage.

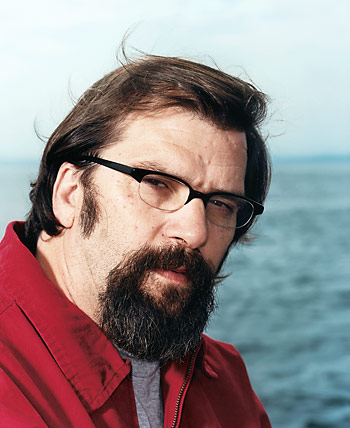

I wander toward the rear of the tour bus, where I find Earle lounging in shorts, sandals and a faded T-shirt with a Hawaiian print across the middle. In better physical shape than he’s been since the late ‘80s, Earle now sports a mustache and goatee. Combined with his new bifocals and the pipe he’s taken to of late, Earle assumes a professorial air, a fitting look for a man who recently taught a songwriting class at Chicago’s Old Town School Of Folk Music. His book of short fiction, Doghouse Roses, is due out in the spring, and a hybrid volume of haiku and on-the-road journal entries is currently being shopped to publishers. Earle penned an article on Emmylou Harris for novelist John Grisham’s award-winning Oxford American magazine, as well as liner notes for last year’s reissue of the landmark Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison album. Lately, Earle has been wearing his playwright hat, working on a drama based on the life and death of Karla Faye Tucker (who, in 1998, became the first woman to be executed in Texas in more than a century) for his Nashville theater company.

Earle has been a tireless agitator for abolishing capital punishment. “I’m really more involved in the political solution to [the death penalty] than I am in activism at this point, not that I’ve given up on activism,” says Earle. “I just believe that these are laws that can only be changed by lawmakers, and I’m involved in the Justice Project. [The organization isn’t] about abolishing the death penalty. It’s not even about a moratorium. It’s about reforming laws that exist around capital crimes in the belief that if you hold those laws up in the light and try to make them as fair as possible, the only conclusion you can reach is that there is no fucking way to economically or fairly administer the death penalty. That’s why we did away with it in the first place. Europe did away with it because they saw a government completely and totally out of control, and it scared the living fuck out them. They decided that maybe governments shouldn’t have that power anymore. There’s a certain arrogance Americans have that we can lay out one set of rules and do whatever the fuck we want to, and the world is becoming increasingly sick of it. I’m also working in Europe as a worst-case-scenario, fall-back position: to eventually bring economic sanctions against the U.S. for human-rights violations for having the death penalty.”

In 1998, Earle witnessed the execution of convicted killer Jonathan Nobles at the condemned man’s request; Nobles is the subject of “Over Yonder (Jonathan’s Song),” the track that closes out Transcendental Blues.

Steve Earle, a man once barely alive, now seems to be living a half dozen lives all at once. Five acclaimed post-jail albums. Countless tours. A book of fiction. A record label. A theater group. A litany of good deeds in the name of sociopolitical activism. As I recite this list, Earle stares out the tour-bus window. “Yeah,” he says, “sometimes it’s almost like it’s a different career and I’m a different person.”

One reply on “Steve Earle: Runnin’ Down A Dream”

I have loved Steve Earle for a good part of my life. It just awes me to soo what he has been into and the things he manages to overcome. It gives me strength to overcome my own problems whuch are small compared to what he faces I have had the greatest pleasure in seeing his performace 4 times and they never fail to deliver! The initial excitement of securing a ticket then the optimum euphoria to be in the same place as th Great One. Thank you Steve Earle. You make my life brighter and i look forward to seeing and hearing you once again. Hugs to you and your family. Suncerely Dianne