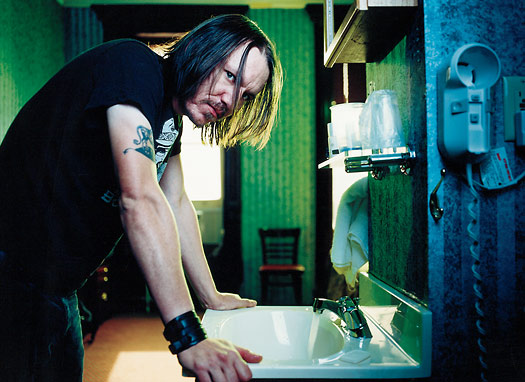

If it’s true that only love can break your heart and that only a love song can help to mend it, then the fitter, happier and more productive Elliott Smith is healing by the thousands. By Jonathan Valania. Photo by Christian Lantry.

With all due apologies to Nick Hornby, here are my desert-island, top five break-ups of all time:

5) Colleen Reese: Beautiful girl. I loved her with all my heart. To quote Weezer, we were good as married in my mind. Sadly, we never lasted past kindergarten. Break-up record: “Seasons In The Sun” by Terry Jacks.

4) Christine Thompson: Golden-haired Teutonic goddess. Because we were the tallest in our sixth-grade class, we always got seated together in the back. Somewhere along the way, she turned into a “bad girl” and got shipped off to Catholic school. Break-up record: “Come Sail Away” by Styx.

3) Tracy Stocker: Cute as a button, head majorette. I took her to the junior-high prom. Didn’t see her all summer, and my terminal shyness around girls forbade me from telling her I still liked her when we met up again in high school. She wound up going out with some jerk who wanted to kick my ass. I should’ve let him. Break-up record: Abbey Road by the Beatles.

2) Lynette Miller: Smart, sultry and voluptuous. High school sweethearts, we lost our virginity together. Probably should’ve married her, though I practically did, as we dated on and off for the next 15 years. Living together put an end to that. This just in: She said yes when the keyboardist in her band proposed onstage a few nights ago. Break-up record: “So. Central Rain” by R.E.M.

1) Jude Gillespie: Breathtaking, ruby-haired beauty with a heart as big as the great outdoors. Really should’ve married this one. She wanted to, but I was too wrapped up in my own bullshit, which is pretty much all she left me with. Break-up record: Figure 8 by Elliott Smith.

And now, it would seem, all my trains have left the station.

Confession: I never liked Elliott Smith. Actually, I never really bothered to check him out. I never liked Heatmiser, so why bother? When the Good Will Hunting/Oscars hype was rampant, I just got sick of seeing his face everywhere in that fucking ski cap. XO, as good as it is, still ranks as my least favorite album of his, although “Waltz #2 (XO)”—the one that goes, “I’m never going to know you now, but I’m going to love you anyhow”—is the best song Smith has ever written. Then Figure 8 came out the month following my number-one all-time greatest break-up, and after a few listens, I knew it was a devastatingly sad and beautiful thing. I gave it to Jude and it made her cry. We listened to it alone in our apartments, shades drawn. I wrote a review for the Philadelphia Weekly. It was a message in a bottle to her:

Elliott Smith still mans the counter at the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart, and as per usual, the customer gets service without a smile. But we keep coming back because we find his misery comforting and his honesty refreshing—he never puts his finger on the scale when he weighs those lonely hearts for us. Thematically, the album revolves around the seemingly conflicting sentiments of “Everything Reminds Me Of Her” and “Everything Means Nothing To Me,” which, it is surely no accident, appear back to back on Figure 8. Wrapped in Smith’s honeyed falsetto, they form a Zen koan no less mysterious than “the sound of one hand clapping” and no more ordinary than “boy meets girl, boy loses girl.” Wars are fought over less. The Stones could make a dead man come. Big deal: Elliott Smith can make a grown man cry.

It did, I’m not ashamed to admit. Figure 8 was a comfort, a friend and a knife in the heart during the long, lonely months that followed. Sure enough, nothing else I heard all year came close in terms of beauty and heart. I vowed to meet the man who, in my mind, had become the Buddha of the brokenhearted, the dalai lama of lonesome town—the man who looked in the mirror without pity and sang, “Nobody broke your heart, you broke your own/Finish what you started.” Smith writes and sings about love with such wrenching elegance and conviction, such tenderness and mercy, surely he could tell me what it is about the mechanics of romance I obviously fail to understand. In my fantasy, I would go to the mountain and wait for hours for some cryptic utterance, a tear-stained wisdom, a mantra that would put in order all the jagged clutter of a shattered heart. Or something like that.

So here I am in San Francisco, on the second-to-last night of Smith’s third U.S. tour in support of Figure 8. We’re sitting in the dressing room of the Warfield Theater before the show. Sporting a thrift-store T-shirt with the word “Bocephus”—the nickname of Hank Williams Jr. (the bad Hank)—across the front, Smith is the same badly drawn boy you see in photos. Unshaven for days, his lived-in face framed by long, dirty hair, Smith looks like Christ after three days on the cross. He is, of course, wearing that brown ski cap, which, one imagines, cocoons him from the harsher frequencies of the world around him. He speaks like he sings, with a soft intensity that can still a noisy room. The first thing I hear him say is, “If there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s winners.” I have come to the right place.

Elliott Smith is happy. Honest. Never been happier. Right now, there’s no place he would rather be than on tour, because everyone knows this is nowhere, and it feels like home. If he looks thin and tired, well, he often forgets to eat, and he didn’t sleep well last night. He had a nightmare that he killed some people. Smith’s dreams have been riddled with violence the past few nights. “They weren’t all me killing people,” he says. “I mean, I’ve never killed anyone. And I never would. Weird how you always forget your dreams—like you’re supposed to forget. All this subconscious stuff is meant to crystallize momentarily and then dissolve.”

Smith takes the stage with his lonely-hearts-club band—longtime friend/Quasi frontman Sam Coomes on bass, crack drummer Scott McPherson (who played in Sense Field) and a cowboy-hatted multi-instrumentalist who goes by the name Golden Boy—and with a heavy sigh, he proceeds to pluck one melancholic folk/rock gem after another from his five albums, holding each one up to the light where it sparkles while his guitar gently weeps. Nearly two hours later, Smith is joined onstage by Grandaddy (his hand-picked opening act for this tour) for a tear-jerking cover of George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord.” That the Beatles are Smith’s favorite group should come as no surprise to anyone who has heard his music. He’s a George man, and he channels that dark-horse melodic vibe with psychic aplomb.

After the show, there’s a meet-and-greet for various VIP types and radio contest winners. For Smith, meeting people isn’t fun, but he gamely endures this concession to DreamWorks (his record label for the past three years), armed with his ever-present Camel Lights and a glass of whiskey. Somebody gives him a book of mystical, quasi-religious writings called The Cloud Of Unknowing. A big, burly guy in nerdy glasses approaches. He’s so nervous he can barely speak, but Smith makes him feel at ease. Smith exudes a certain serenity that some mistake for the listlessness of the depressed, but he has the same calming effect on people as a police horse at a riot. A twentysomething girl tells Smith his songs “fill in the blanks until we can figure out the answers.” I have definitely come to the right place.

Band and crew retire to the tour bus. Smith runs ahead of me and sheepishly hides the straightening iron he uses on his hair, a grooming technique he picked up from the stylist at the MAGNET photo shoot. He’s growing his hair long because he’s “sick of all this short hair, like fucking athlete heroes,” he says. “The cult of the winner—you can’t get away from it.” Beers are cracked open as Smith plays DJ: the Stooges’ Raw Power, the Beatles’ White Album, the Velvets. He reaches for Def Leppard’s High ‘N’ Dry but instead opts to play two new songs he’s recorded in the garage studio at producer Rob Schnapf’s house. One is called “A Fond Farewell To A Friend,” the other “A Dying Man In A Living Room.” Like just about everything else Smith has ever recorded, they sound like the same sad song—a great song, to be sure—that he keeps getting better at writing, arranging and singing.

Smith is in a playful mood. Presumably for the sheer silliness of it, he wants to switch tops with McPherson, who’s wearing a white wife-beater T-shirt. Smith shyly runs to the other end of the bus, and when he takes off his shirt, he looks frail and vulnerable, and with his long, greasy hair and grubby beard, you don’t have to squint too much to picture him on the cross. He reemerges with his pencil-thin arms poking out of the wife-beater to a chorus of chuckles and guffaws. He doesn’t look like a winner. And he’s, like, fine with it.

From those to whom little is given, little is expected. Thirty-one years ago in Omaha, Neb., Elliott Smith was born with little or no expectations, save a secret, special gift he wouldn’t discover for many years. He grew up in and around Dallas, and he really doesn’t care to talk about it, thank you. Smith would rather not open old wounds in any family member who might read this story. “Most of my recollections from that time I really wouldn’t want to share on the record,” he says succinctly when the subject is broached.

Smith will say this much: When he was 10, he took piano lessons for a year, pounding out Debussy and Rachmaninoff on an electric piano that would, from time to time, pick up the CB transmissions from passing truckers. That, and the first record he bought with his own money was Kiss’ Alive II. “I thought it was really cool that Gene Simmons had blood running down his mouth,” he says. When Smith was 11, his father gave him a guitar, and young Elliott set about teaching himself to play and write songs.

Smith has written several songs about his mother, most notably “Waltz #2 (XO)” (that’s her at the karaoke mic singing “Cathy’s Clown”) and “Pretty Mary K” (his mother’s middle name is Kaye). His parents split when he was one, and his mother soon remarried. When he was 14, Smith moved to Portland, Ore., to live with his father, a former preacher who served as a pilot in Vietnam before becoming a psychiatrist. This is another period of his life Smith plays close to the vest.

“I was all twisted up at that time,” he says. “There’s not much that I could say about that time that I would like to see in print. I wouldn’t want to remind any of the people involved about that time.”

When did he start to feel “untwisted up”?

“As soon as I didn’t live with anybody.”

In 1987, Smith followed a girlfriend to Hampshire College, an über-liberal-arts school in Amherst, Mass., with no grades or classes. He read a lot of Sören Kierkegaard—remember that, Kierkegaard—before heading back to Portland in 1991. For a time, he toyed with the notion of becoming a fireman. Instead, he joined Heatmiser, though it would seem his heart was never really in it. When you’ve grown up around a lot of yelling and screaming, the last thing you want to do is be in a band where everyone is yelling and screaming, he once told an interviewer.

In secret, Smith pondered the pristine liquidities of the perfect melody, honing a private vision of what sounds good: whispery, campfire acoustica and a hoarse flicker of a voice illuminating the dark corners of love, loss and regret. In 1994, Portland’s Cavity Search Records offered to put out a seven-inch, and Smith gave them a cassette of nine songs to pick from, half of which didn’t even have titles. Blown away by the quality of the material, the label offered to release it as an album. It would be called Roman Candle.

Smith followed it up in 1995 with an eponymous second album issued by the Kill Rock Stars label. Much like his debut, the LP publicly chronicled private disintegration—romantic, chemical and otherwise—on songs like “Needle In The Hay,” “St. Ides Heaven” and “The White Lady Loves You More” that would crystallize his junkie-saint image. It remains unclear to what extent Smith was holding a mirror up to himself or those around him, but it was all delivered unflinchingly and without apology. “Shoot me up, it’s my life,” he would later sing.

By the time of 1997’s Either/Or, things were beginning to fall apart. Smith’s drinking was getting out of hand: blackouts, alcohol poisoning, getting into fights he couldn’t remember, waking up on the street covered in cuts and bruises. Friends staged an intervention in Chicago in the middle of the Either/Or tour.

“I got kind of weird,” says Smith. “I started drinking too much and I was taking antidepressants, and they don’t mix. But I got this strange kind of optimism going, even though the way I was living wasn’t showing it. But mentally, I started demanding I be productive and positive.”

With the help of the Paxil he still takes, Smith managed to will himself into a happier place. “Things are going to work out, and I’m never going to stop insisting that things are going to work out,” he would tell himself.

Then the clouds began to part. Filmmaker Gus Van Sant, a fellow Pacific Northwesterner, came knocking with the reels of Good Will Hunting under his arm. Within a year, Smith signed to DreamWorks and performed “Miss Misery” before a television audience of millions on the Academy Awards. XO, his ornate major-label debut, was released in 1998 to rave reviews and a heightened media profile, not to mention a swelling cult of crushed romantics—some listened to remember, some listened to forget—who crowned him the sun king of rainy mood-pop. After the endless touring that followed, Smith relocated to Los Angeles to begin work on Figure 8. It struck many fans as a strange move for a man who always seemed more at home in gray, drizzly climes.

“When I tell people I live here, it’s like people expect me to apologize for it,” he says. “But there’s nothing wrong with Los Angeles. The past couple of years, it hasn’t really mattered where I lived because I haven’t really been anywhere. I’ve been at home maybe a total of three or four months in the last two-and-a-half years. There’s no real reason for me to be in one place instead of another. It’s so sunny here and people like to drive expensive cars and like to live here because it looks so positive during the day. But at night, it’s just like any other city. I go out and see people drinking themselves into oblivion. I never thought I would live here. I’m not that into the sun or beachiness. But I like weather—it makes it seem more like the world is a person with moods.”

Tired of being pegged by reviewers as a velvety miserablist, Smith put forth a conscious effort to make Figure 8 an “up” record. “It’s actually really hard to write a happy song without sounding corny,” he says. “Some people are really good at it, like Smokey Robinson. ‘I Second That Emotion’ is really positive, and it’s not corny. That’s probably because you don’t get the impression that Smokey Robinson never had a bad day in his life, so he sounds strong when he is being positive.”

Kierkegaard, the father of existentialism, said that if you make yourself ignorant to the futility of attempting the impossible, anything is possible. That’s the message embedded in “Stupidity Tries,” Figure 8’s spiritual anchor. “I realize that there’s no real point to me doing what I’m doing,” says Smith. “But if that was at the forefront of my mind, I would get nothing done. And that would be really boring.”

On a lark, Smith mentioned to DreamWorks that, uh, it might, like, be cool to record some of Figure 8 at London’s famed Abbey Road Studios. Within a month, Smith was sitting at the same piano used on “Penny Lane,” working out parts for a 40-piece string section assembled in the main studio. Before flying to England, he received a fax from George Martin, the aural wizard behind the Beatles’ magic, saying someone had passed along one of Smith’s albums and he really liked what he heard. Martin left his phone number, suggesting Smith call if he ever got to London. You can imagine what it meant to this kicked puppy of a kid who salved the wounds of a joyless childhood with the Beatles’ sunny pop manna. Unfortunately, Martin was out of the country when Smith arrived in London. But that’s OK, because things are going to work out, and Smith is never going to stop insisting that things are going to work out.

Elliott Smith is a hugger. Not just with anyone, mind you, but when dear friends he hasn’t seen in months turn up backstage at L.A.’s Wiltern Theater, he clasps them in a warm embrace. Here comes Autumn de Wilde, who takes all of Smith’s publicity photos and made the impressionistic film that’s played onstage behind Smith and band on this tour. She’s accompanied by her husband, Aaron Sperske, who plays drums in Beachwood Sparks. For the cover of Figure 8, de Wilde posed Smith in front of a trippy mural outside a stereo-repair store on Sunset Boulevard. A shadow over Smith’s head rendered his hair invisible, so the boyish bowl cut he sports on the cover is actually a computer simulation. “I gave him a choice of three hairstyles,” says de Wilde.

Smith retires to the bathroom to warm up his voice. Coomes idly sketches in a notebook, while Golden Boy fixes himself a Dagwood sandwich from the deli tray. McPherson sits alone, smoking; he’s heading home tomorrow to Portland, where he plans to hang up the drumsticks for good and go back to college. “Wanna hear a joke?” he asks earnestly. “Kid says to his dad, ‘When I grow up, I want to be a musician.’ His dad says, ‘Son, you can’t have it both ways.’“

I notice a print-out of an e-mail sitting by the deli tray. It reads:

Hi Elliott Smith,

I am Annelise Shafer. I am nine years old and one of your biggest fans. You sent me a poster with your autograph on it. I am going to your concert on Tuesday in Los Angeles and will be sitting in the ninth row on the side. I hope you see me.

Love,

Annelise

Down the hall, Smith’s tour manager Miles Kennedy, a dead ringer for a young Roky Erickson, is sorting out the guest list. This being L.A., the names have marquee value: Beck, Keanu Reeves, the gals from the TV show Felicity. Onstage, Grandaddy is gently massaging the satellite heart of its sublime, space-age pop as the venue begins to fill. Grandaddy has been winning converts in every town. Word has it that when the tour stopped in New York a few weeks back, David Bowie came specifically to see Grandaddy. In the lobby, I run into Annelise. I tell her that Smith got her e-mail. At the tender age of nine, she has yet to master the media sound bite, but suffice it to say, she’s pretty psyched. (The look on her face when she gets to meet him after the show is priceless.)

Smith walks onstage and strums those jittery chords to “Needle In The Hay”—his left leg trembling, telegraphing the intensity his hushed vocal delivery only hints at—and the faces in the crowd brighten as if someone lit a sparkler. The song sounds somehow different than it did all those years ago, like it’s no longer a travel diary from the road to oblivion. Tonight, it sounds like a gilded cage where Smith keeps those old demons locked away, close enough to remember but just out of arm’s reach where they can never hurt him or anyone who cares about him ever again.

Elliott Smith is finally home: a cozy, 1920s bungalow nestled on the side of a tree-shaded hill in Los Angeles’ Echo Park section. It’s not quite the Himalayan perch I had envisioned for my audience with the sage of sadcore, but in Kansas, this would definitely be considered a mountain. One of Smith’s managers occupies the bungalow next door, and up the hill live de Wilde and Sperske, in a bi-level home that’s become the de facto headquarters of Beachwood Sparks. Smith and I head up there and sit down on the couple’s balcony. It’s noon on the day after the Wiltern show, and Smith, not having gone to bed until 8 a.m., catatonically sips at the first of three quadruple espressos Sperske serves him. Soon, Smith is vibrating with a caffeine buzz so strong it makes his beard itch. Magic Markered across his fingers are the words “H-I-G-H T-I-D-E” in elegantly rendered calligraphy. It seemed, he explains, like a good idea at the time. After an hour or so of chatting about Figure 8 and all that led up to it, I finally get around to the big questions I have traveled thousands of miles to ask.

Do you believe in God or some kind of supernatural agency at work in the world or, as science would have us believe, that reality is just an illusion created by a series of chemical reactions in the brain?

I have my own idiosyncratic version of that. I was brought up in a religious household. I don’t go to church. I don’t necessarily buy into any officially structured version of spirituality. But I have my own version of it, of which I’m the only member. I see no reason not to believe in whatever I want to. I almost don’t care if I’m correct in what I believe. If there’s nothing more than what you can see happening, that would make the world seem so small.

What do you think happens when you die? Do you become part of some greater whole, some universal soul, or are you just worm food? Do you prefer burial or cremation?

I don’t really know what happens when you die. I don’t like the idea of being buried. I would prefer to walk out into the desert and be eaten by birds or something. The idea of being buried under the ground or being burned up doesn’t appeal to me. I’d rather be eaten by birds.

Do you think suicide is courageous or cowardly?

It’s ugly and cruel and I really need my friends to stick around, but dying people should have that right. I was hospitalized for a little while and I didn’t have that option, and it made me feel even crazier. But I prefer not to appear as some kind of disturbed person. I think a lot of people try to get mileage out of it, like, “I’m a tortured artist” or something. I’m not a tortured artist, and there’s nothing really wrong with me. I just had a bad time for a while.

Love seems to be the engine that drives your art. How many times have you been in love?

Real love? Once.

How did you know?

I just knew. I knew it when it was there.

Can you ever truly stop being in love with somebody?

It just changes into a different kind of connection with someone. People make a distinction between being in love or the kind of love that really just means they are strongly connected and care about someone. I think you can slip out of being in love with someone and just become really connected with that person and not really realize it while it’s happening.

Are you in love right now?

No, not really, uh … It’s a really good subject to talk about, but I’m afraid it’s going to bum somebody out.

Do you believe, as the poets say, that love is the only thing that gives any meaning to the universe, and that without it, we are just a bunch of molecules bumping up against each other?

Yes. Love or some kind of creative act.

Aren’t you terrified by the possibility that you may never again find true love?

If I was sure that love was not coming my way again, I wouldn’t see much point in doing anything. It’s a distinct possibility. But, you know, stupidity tries.

And then it’s over. The credits roll, and the hero wins the fight but he doesn’t get the girl. I walk back down the hill, silent and dejected. These weren’t the words I was looking for. It’s probably my fault. I didn’t ask the right questions. What the hell was I thinking about all that pretentious crap about God and death and molecules? Chris Farley did a better job interviewing Paul McCartney. Or maybe all along, Elliott Smith was just some guy who sang pretty songs.

But when I get to the bottom of the hill, I begin to think that while maybe these weren’t the words I wanted to hear, these were the words I needed to hear. This sage wisdom stuff is supposed to be kind of sneaky. Two things you should always remember and never forget: Kierkegaard—who wrote a book called Either/Or in 1843, when books were the rock ‘n’ roll albums of the day—basically said that life is a cosmic joke and then you die. Yet even though we know this, we carry on, and that’s heroic. The Beatles—who released Abbey Road in 1969 (the year Smith was born), when rock ‘n’ roll albums were the books of the day—more or less summed up themselves, the ‘60s and the meaning of life when they sang, “And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

2 replies on “Elliott Smith: Emotional Rescue”

pretty shitty article

It’s eerie that Valania made the “knife in the heart” remark back in January of 2001.