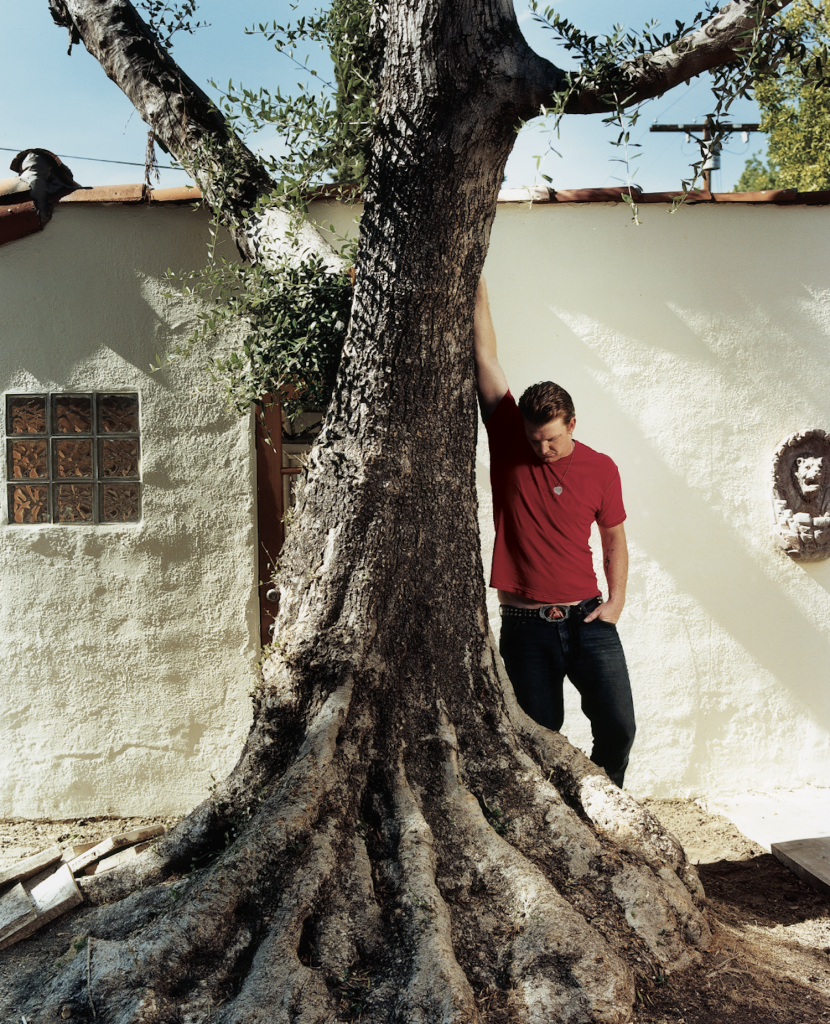

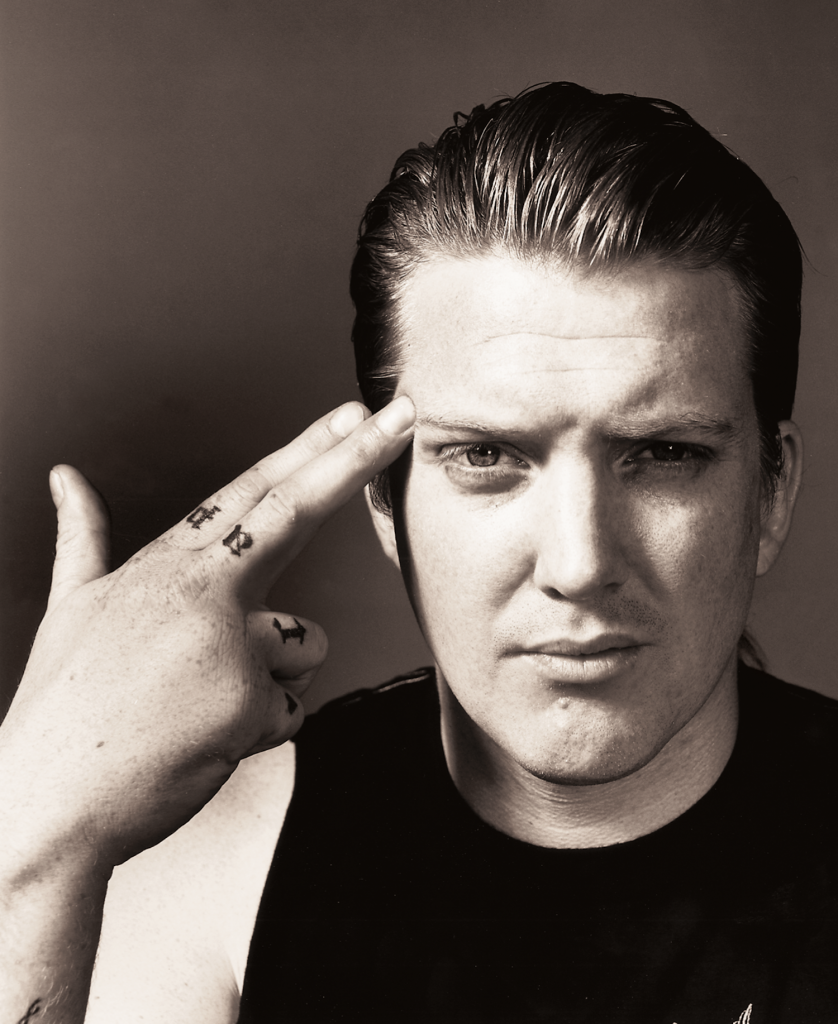

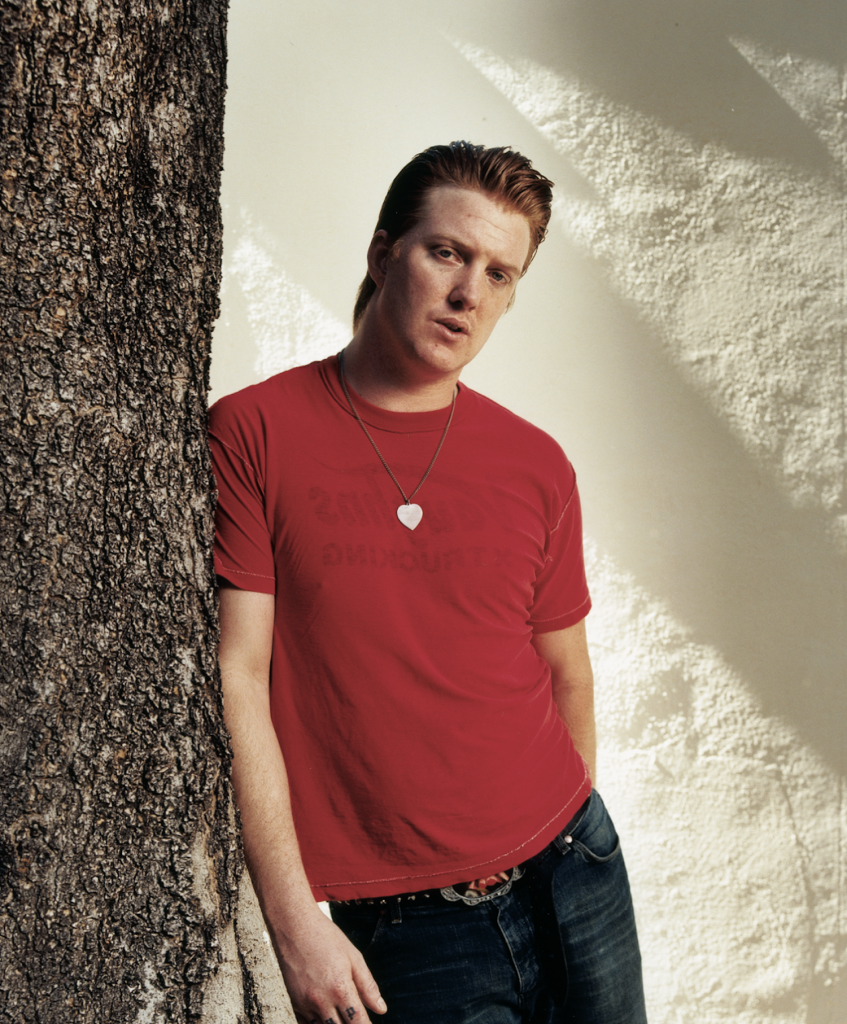

Whether leading Queens Of The Stone Age or following his own freak-friendly muse, you will know Josh Homme by the trail of dead-weird disciples, ringing ears and a cloud of desert dust. By Matthew Fritch. Photos by Dennis Kleiman.

Baby Duck peels outta Pioneertown in his 1967 Camaro and heads for the high-desert night. In the passenger seat, Little Timmy fishes into his jacket pocket for the wounded soldier he smuggled out of the bar and puts it out of its misery. Timmy’s kinda tipsy, and he begins to sing a tune that sorta resembles Petula Clark’s “Downtown” by way of Broadway belter Ethel Merman. Except the words are real different:

“Diiiiiccckk baaaalllllsss! Everything’s coming up diiiiiccckk baaaalllllsss! Everyone’s asking ’bout diiiiiccckk baaaalllllsss!”

Timmy stops his show to giggle or shriek whenever Baby Duck floors his silver sports car around a curve or rollercoasters it through a dip in the road. The Camaro is trailed by Party Vehicle number two, a Ford Explorer containing the rest of the gang: J Devil, Joey the Muscle, Big Al and Troy, who’s also called Dapper Dan. After a tequila refuel at the 24-hour liquor store, they continue east on 29 Palms Highway toward Joshua Tree. The cars hang a left onto a dirt road; tires kick up dust and headlights illuminate the eyes of a jackrabbit bounding along the path to the final destination: Rancho De La Luna.

A stray dog ambles up to greet the masters of the house, who file inside and collapse on couches and chairs. There’s a giddy anticipation as, one by one, instruments are taken up: Baby Duck flips the switch on a box-shaped machine he calls the Annoyatron, a vintage harmonic oscillator that emits a wavy, UFO-landing-in-the-backyard sound effect. Over on the couch, Timmy cradles an acoustic guitar and finds a few chords that have legs, playing them over and over before Joey strikes a primitive beat using just a kick drum and muted cymbals. Troy, cross-legged on the floor, eases in on the lap steel and joins the swinging pendulum of song. The music moves like heat waves on a summer horizon, refracting the rhythmic peaks and troughs into one woozy, miasmic noise.

J Devil paces the floor near the coffee table and occasionally stutters the random, primal phrases of blues songs: b-b-b-baby’s gone, I’m l-l-lonely and so on. You blink and then it’s hours later, and you still hear it. And then you’re a half-mile away from Rancho De La Luna, walking down the dirt path with only the Wednesday night sky as your witness, and you still hear it. And then you’re in the motel where Gram Parsons died, and you still hear it.

***

In the stark light of morning, the explanation goes like this: Baby Duck—the stroker ace behind the wheel of the Camaro—is the nickname of Josh Homme (rhymes with “Tommy”), who plays guitar and sings in a hard-rock band called Queens Of The Stone Age. The Queens are the kind of band that makes you feel cool when you listen to their music. Importantly, the “you” in the preceding sentence means you the metalhead, you the punk, you the indie rocker, you the pop-radio listener, you males and you females.

The Queens are currently experiencing some turbulence—we’ll get into that later—so in the downtime, Homme has taken up drumming for the Eagles Of Death Metal, a band he formed with childhood friend Jesse Hughes (a.k.a. J Devil) and Belgian native Tim VanHamel (our Little Timmy). The rest of the players are members of Queens Of The Stone Age: guitarist Troy van Leeuwen, multi-instrumentalist Alain Johannes and drummer Joey Castillo. The nicknames are just for fun. You remember fun, right? It’s what happens when some dopey guys from Queens all decide to go by the last name Ramone or a scrawny British folk singer puts on makeup and seriously presents himself as a guitar-playing martian.

Hollywood built Pioneertown in 1946 as a Wild West set for Roy Rogers and Gene Autry, but today it’s a touristy strip of souvenir shops and old-timey saloons. Rancho De La Luna—which sounds like either the name of a space-age dude ranch or a Mexican restaurant—is a rather ordinary one-story house. It’s set a half-mile back from the highway that runs through Joshua Tree National Park, connecting the ritzy retirement oasis of Palm Springs (the city has more per-capita swimming pools than anywhere else in the world) with a military training and weapons-testing facility called 29 Palms. Rancho De La Luna, with its interior maze of amplifiers, sound boards and instruments, has a cluttered-dormitory feel to it, with thrift-store furniture and a few horsey paintings hanging on the walls.

The motel where Gram Parsons died is less than a mile from Rancho De La Luna. Because of strong winds and the lack of geological barriers, sound can travel in peculiar ways out here. This desert valley is home to massive wind farms; some 40,000 windmills crank out electricity that’s sent to Los Angeles, about 100 miles away.

Oh, and “Dick Balls.” A spontaneous composition. It’s much funnier when sung/slurred in VanHamel’s Flemish accent (similar to a Schwarzenegger drawl, but with a Scandinavian lilt), hurtling through the desert night at 70 mph. And its melody more closely resembles Bill Murray’s Saturday Night Live lounge-act character singing a made-up theme to Star Wars. Point is, if any of this gets too serious or heady, let’s just remember “Dick Balls.”

***

“As soon as you learn to walk, you start walkin’ right out of town.”

Gram Parsons, the Byrds guitarist who went on to blaze his own country/rock vapor trail in the early ’70s, said that about his narrow-minded hometown of Waycross, Ga. Parsons’ path came to a dead end on Sept. 19, 1973, in room eight at the Joshua Tree Inn, where he’d come to bottom out. A casualty of the collision between the free-love/free-drugs ’60s and the costly excess of the ’70s, Parsons often visited the desert to pal around and party with the likes of Keith Richards and Emmylou Harris, seeking the essence of what he called “cosmic American music.” The 26-year-old Parsons died of heart failure, and a coroner’s report indicated a lethal amount of drugs in his blood stream. Friends impersonating hearse drivers stole the musician’s body from the Los Angeles airport and drove back out to the desert, where, according to Parsons’ wishes, they burned his corpse.

Josh Homme, who was born the same year Parsons died, doesn’t care much for the lazy-hazy style or sound of Southern California country/rock, having grown up with the more pragmatic noise and ethos of SST punk. Like Parsons, Homme initially sought to escape from his hometown (Palm Desert, “the golf capital of the world,” about 30 miles from Joshua Tree). A strong, athletic kid who was always six inches taller than the rest of his classmates, Homme knew sports—football, in particular—would be the easy way out. But music seemed like the higher road.

“Each person has their mountain to crawl,” says Homme. “And the fact that I’m six-foot-five … I didn’t want to be perceived as some jock guy playing heavy music, like, ‘Aaarrrghhh!’ All kids are angry at some point, and they don’t even know why. That’s why punk rock is such a welcome hug. It embraces youthful anger. But I really wanted people to recognize I was passionate about music, and I happened to be big. I wanted to play music, and other people wanted me to play ball.”

As a teenager, Homme fell in with a core group of friends that’d eventually make up his first proper band. Consisting of Palm Desert High School football teammates Brant Bjork (drums) and John Garcia (vocals), along with local badass and dropout Nick Oliveri (bass), Kyuss spent the early ’90s forging punk/metal epics with magma-thick guitar riffs and sludgy, psychedelic noise. It was a musical formula arrived at by necessity: In order for sound to carry in the desert canyons where Kyuss staged shows powered by portable generators, all amps had to be turned up and all guitars had to be tuned down. By the time Kyuss split in 1995, it had unwittingly helped spawn stoner rock, a dead-on-arrival subgenre full of longhaired bands playing longwinded, laborious metal.

“When (the term) stoner rock was created,” says Homme, “I was one of the first ones to go, ‘Fuck this shit.’ It’s just a new box, and I helped to build it. I said I’d build a house—I didn’t say I’d live in it.”

When he was 22, Homme made an abrupt exit from the stoner-rock scene, traveling to Arizona and then Seattle, where he planned to attend college and major in international business. But in 1996, he accepted a job as touring guitarist for the Lollapalooza-bound Screaming Trees, a band in the midst of horrible internal feuding. Rather than suffer through awkward silences in the Trees’ bus, Homme signed up to drive a truck carrying gear for tourmates the Ramones, following C.J. Ramone and a friend on their motorcycles along the Lollapalooza trail.

“I was driving for days and days, and then we would stop to play rock ‘n’ roll music,” says Homme. “I was in Mexico and the sun was setting, and they were on their bikes. I was listening to [Iggy Pop’s Lust For Life and The Idiot] and pictured myself in the classroom, and I was like, ‘Am I crazy?’”

After his stint with the Screaming Trees, Homme made a beeline back to the desert, where he reconnected with late-period Kyuss drummer Alfredo Hernandez and Oliveri (who’d spent the intervening years playing with, and getting kicked out of, legendarily lawless punk outfit the Dwarves). Homme knew he wanted to play music that was sexier and more melodic; he wanted to bridge the gender gap created by metal’s macho posturing and be a little absurd while doing it. Hence the name of his new project, Queens Of The Stone Age. At the same time, he discovered the trancelike rhythms of ’70s krautrockers Neu! and Can.

“When I heard [those bands],” says Homme, “I was like, ‘Damn, other people have done this already?’” But Queens Of The Stone Age would become a juggernaut of new ideas, their hybrid sound generating previously nonexistent genre names. 1998’s self-titled debut was clunkily labeled “robo prog.” 2000’s Rated R and 2002’s Songs For The Deaf, both featuring a three-headed vocal lineup of Homme, Oliveri and former Screaming Trees frontman Mark Lanegan, offered a mixed bag of desert rock’s heavy psychedelia, pop-polished metal and razor-sharp punk. Based on the label’s success with weird-ass bands like Primus, Homme signed to Interscope Records prior to Rated R. The Queens’ major-label status opened up a few doors—a spot on Ozzfest, radio/MTV airplay, Dave Grohl behind the drum kit—but the band never really joined the nü-metal party. For someone like Homme, who came up in a punk scene that dictated you could do well but not too well, his band’s success meant facing up to some long-standing unwritten rules.

“Long ago I gave up on punk rock because it became more of a fashion thing,” says Homme. “I also realized that I’m more punk than the most mohawked, spiked-up, Germs-shirt-wearing motherfucker I could see. Because they don’t infiltrate and destroy like punk rock’s supposed to. How do you kill the king? You don’t knock on the drawbridge door with a mohawk and go, ‘Heeeyyyy! Fuck you and your rules!’ I like it to be more of a chess game, a better way to break down the machine. Not the machine like ‘The Man,’ but any machine I see, ever, anywhere, wherever it is.”

Like fellow snake-oil salesmen in Ween, Primus and the Flaming Lips, Homme has mastered the fine art of duping a record label—or, at the very least, convincing the suits it’s a good idea to lead off an album with a song featuring the mantra “nicotine, Valium, Vicodin, marijuana, ecstasy and alcohol.” Admittedly, the Queens’ exploits are only slightly unconventional—no clear lead singer, free-ranging side projects—but the band is able to navigate popularity using its own compass.

“What I love about the music business is the thing I used to hate about it,” says Homme. “Every time I release an album, I know exactly what the record company wants. It’s one of the few predictable things. It’s more predictable than the fans and even your own music. They would like, if it’s OK with you, to sell records. I’d like to think that they understand by now that I like dark pop tunes that are three minutes long. So the question is, ‘How do I get them to sell records exactly and only how I want to, with them thinking it’s exactly and only how they want to?’”

***

Queens Of The Stone Age are currently unable to strategize against the predictable machine in quite the same way as before. Lanegan departed amicably earlier this year to concentrate on his solo career.

“I think it’s a lot to ask of a guy like Mark to sing six or seven songs a night,” says Homme. “But I wouldn’t be surprised if you were at a show one day and he walked onstage. He’s got an EZ-Pass. A get-into-jail-free card.”

In February, Oliveri was fired from the group due to what Homme terms “personal differences.” In some ways, it was the superficial contrast between Homme (a clean-cut, well-adjusted, all-American with a soft, velvety voice) and Oliveri (a punk-rock Anton LaVey with a murderous scream) that kept the Queens balanced. But for anyone who’s followed Oliveri’s escapades over the past few years—what amounts to a long rap sheet of violent behavior, antagonism toward fans and self-destructive tendencies—it’s easy to see how he alienated himself from the band. Homme can’t point to a specific incident that led to Oliveri’s ousting but says it was due to accumulative offenses. In other words, Homme just got tired of running with the devil.

“It was all the keeping people on eggshells,” he says. “I was the only one in the position to [smooth things over]. Nick still doesn’t even know why he was kicked out. And that’s part of why. You should not kick the luxury of being in a rock ‘n’ roll band in the balls. If you’re not playing well, you don’t destroy all the equipment and hit someone in the audience. That’s not what we do here at the Queens Academy. I’m not your daddy or nothing, but I don’t really think you should be doing that. Because I don’t want to be involved with something like that.”

Oliveri declined to speak with MAGNET, but a February 15 statement on the website of his solo project Mondo Generator refers to the new version of his former group as “Queens Lite” and indicates a power struggle was the reason for his dismissal: “A pure idea has been polluted … The concept was simple: A ROCK BAND, selfless, mindless, ego-free, unprotected, about danger, sex, and no-bullshit rock ‘n’ roll. You know what happens when a pure and original rock band gets polluted, poisoned by hunger for power, and by control issues? Things get really out of control. I’m noticing that people start fighting for control, especially when they realize they have no control. And what ever happened to loyalty?”

In fairness to the feuding parties, the Queens maintained a brutal touring schedule in 2002-03, playing everything from Lollapalooza and Australia’s Big Day Out festival to packaged tours with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Distillers and Trail Of Dead. Homme coldly attempts to explain that Oliveri was a casualty of the Queens’ onward march—a body left on the side of the road—but it’s obvious the loss goes far beyond the confines of band membership.

“The only thing that sucks is that me and my longtime friend are not agreeing,” says Homme. “For everyone else, it’s something they think of for maybe five seconds or not at all. I’ve been asked all manner of questions: ‘How can you possibly play live without Nick?’ My answer is: ‘Because I can. I just will.’ And I get asked a lot of what-if questions (regarding Oliveri). Well, what if your dick catches on fire, turns into a snake and bites your asshole?”

***

“Should I wear the cape? I don’t know if I should wear the cape. If I wear the cape, you can’t see my ass. I want everybody to be able to see my ass.”

Jesse Hughes is primping backstage at Late Night With Conan O’Brien, where the Eagles Of Death Metal are performing the 18th show of their seven-month career. Hughes not only worries about the gold lamé cape with the black lightning bolt on the back—which he tailored himself—but also wonders whether to wear a belt made of bullets. Bandmates Homme and Tim VanHamel are both TV-appearance veterans (the latter is the singer/guitarist for Millionaire, which enjoys a good deal of popularity in its native Belgium) and look on with mild disinterest. The Eagles’ backup dancers, a pair of Jersey-haired ladies in pink prom dresses, practice their shimmy moves and handclaps in the dressing room, then scurry off to make-up in order to apply their mustaches. The girls are wearing fake mustaches because, says Hughes, “it’s the soft, fuzzy boomerang of love.”

The worst thing you can probably say about the Eagles Of Death Metal is they may not be entirely serious; fortunately, that’s also their most redeeming quality. The trio recorded its debut, Peace Love Death Metal (AntAcidAudio), in three days at Rancho De La Luna last year. It’s by no means a groundbreaking or profound album; it’s only rock ‘n’ roll. In fact, singer/guitarist Hughes will readily admit his songs blatantly rip off the Damned, David Bowie, Ween and the Stones.

“My level of pretense hasn’t yet developed to the point where I’m going to bullshit you,” says Hughes. “But Eagles songs are stolen from some of the best music in the world, so technically, this should be the best music ever.”

“People forget how much music is entertainment,” adds Homme. “It’s not anything else. It can be entertainment that’s deep and very cerebral, but it can be in the shallow end of the pool, too. But when you’re in the shallow end, you can be standing holding a drink and a smoke, so the shallow end is not that bad, either. At least you have the option to swim toward the deep end when you’re done.”

While Hughes doesn’t seem to be lacking any tight-pantsed swagger before his debut on national TV, he nevertheless slips a Thin Lizzy CD into the dressing-room boombox to get himself in the mustache-rock state of mind. VanHamel does a loose-limbed jig that Homme describes as “a monkey octopus on LSD, but Belgian.” The Eagles Of Death Metal go out and give it their best shot, playing “So Easy” (whose main guitar riff, Hughes confesses, was lifted from Pentagram’s “When The Screams Come”). No disrespect to the actual music, but the highlight of the performance is watching VanHamel windmill around the stage and contort his face into an expression of constant surprise.

Some minor congratulatory partying ensues back in the dressing room. Homme dials Distillers singer Brody Dalle, whom he’s been dating for the past year. Dalle—known in Eagles circles as Queen B—contributed backing vocals to Peace Love Death Metal’s “Speaking In Tongues,” and Homme fully intends to collaborate further with her. “We’re just waiting for you all to be ready,” he says, “to get over the petty drama side of it.” The drama, incidentally, stems from the fact Dalle used to be married to Rancid singer/guitarist Tim Armstrong. Homme and Dalle raised music-press eyebrows when the two announced their relationship by locking tongues at a Rolling Stone photo shoot in spring 2003.

Hughes attempts to call his four-year-old son Micah but is told the boy is napping. Before everyone files out of Conan, Homme plays den mother and instigates a well-organized cleanup campaign of the dressing room, clearing the coffee table of debris and disposing of plastic cups and beer bottles: “I want them to say, ‘They were a horrible band, but they were so tidy.’”

***

At 31, Jesse Hughes feels like he just won the rock ‘n’ roll lottery. The day after the Conan taping finds him lounging around the lobby of New York City’s posh W Hotel, cracking jokes with the bellhops, conducting phone interviews with journalists and ogling the uptown girls who pass by on their way to the elevators. Hughes is—and there’s really not a flattering way to put this—a total spazz who looks like Ned Flanders from The Simpsons recast as a leather-clad porn star. But it’s all part of his charm, and it’s integral to the revenge-of-the-nerd tale wherein a benevolent rock star swoops in and rescues his high-school buddy from a life of tedium. According to Hughes, Homme showed up at his door on New Year’s Eve 2002 and posed a simple, life-altering question: “Do you want to play some rock ‘n’ roll?”

“Believe me,” says Hughes, “I’m very aware of the fantasy element of this story.”

At the time, Hughes was in the midst of a painful divorce, renting an apartment in Palm Springs and managing a chain of video stores. Whenever Homme happened to be in town, the two would meet for a drink, but Hughes never went to see the Queens play. Mostly, they’d just chat about old times.

“Josh and I were both on the soccer team,” says Hughes. “I was captain of the soccer team; make sure you put that in the article. We competed for the league record for having the most fouls committed in a single game. I was a real loner in high school. And I wasn’t a cool, chic loner type. I wasn’t angry at the world; I was into reading. Many times, Josh would save my ass from being ruthlessly beaten down. I was short back then—five-foot-one—and I’d show up for class in a suit and tie.”

Hughes isn’t joking about being an ostracized teen or playing the nerd card; that Benjamin Franklin and Nathan Hale are among those thanked on the sleeve of Peace Love Death Metal isn’t an ironic gesture. A history buff who once worked as a political speechwriter, Hughes rolls up his sleeves to display his tattoos: a pair of green dragons, designed after those carved above Boston’s Green Dragon Tavern, where, he explains, “Ben Franklin and Sam Adams would get loaded and talk about overthrowing the British.” There’s also a tattoo of the federal eagle, the one that appears on the $20 bill. “The original Eagle Of Death Metal,” says Hughes.

Hughes was raised by a grandfather who taught him to play blues guitar, so it’s not like he had never picked up an instrument prior to his career with the Eagles. He’d just always played while sitting down. “My first show in front of people was opening for Placebo,” he says. “I fucked up every song because I could barely stand up and play.”

As idyllic as Hughes’ story seems, you still have to wonder why Homme would cede the spotlight to an amateur and retire to the dim confines of a drummer’s chair. Though Homme says the timing is coincidental, it’s clear the Eagles offer a respite from the recent commotion with Oliveri and the Queens.

“One of the magical things on our mystical tour here is watching Jesse and Timmy appreciate playing music,” says Homme, who arrives in the W lobby promptly after waking up at 4 p.m. “Playing music for your life is such a badass thing. [Hughes and VanHamel] dig it so much that it makes a band have so much solidarity because you have one common thing: You know you’re lucky to be here. When I play with someone who doesn’t appreciate that all of a sudden, I feel like dirt. Musicians who feel entitled aren’t worth spending any time on. ‘Welcome to Negative Land.’ ‘What? These rides suck.’ ‘Come over to the shitdog dipped in cheese. This tastes like shit—taste it.’ Whenever a band I’ve been in has continuously exhibited a distaste for being a musician, I’ve always left or fired somebody.”

“This is my first exposure to the music business,” says Hughes. “I’ve had my best friends in the world guide me through it. I wasn’t promised a rose garden; I’m getting shown I can plant my own roses.”

***

Right about now, you might be thinking what an absolute saint Josh Homme is. Or, at the very least, how he’s been an angel on Hughes’ shoulder. The Eagles Of Death Metal end up spending four days in New York City, optimizing their Conan trip by also playing a club show, a fashion-magazine party and a daytime gig for music-industry types. The Distillers happen to be in town for a couple of nights, and Homme gets to spend some time with Dalle; both evenings, the majority of Eagles and Distillers wind up at Niagara, the East Village bar owned by singer/songwriter Jesse Malin. Both nights also come to the same violent conclusion, with Homme’s temper getting the best of him.

The first incident occurred in a convenience store, which Homme and Dalle had entered to buy some water on their way back to the hotel. Two men repeatedly approached Dalle in a lewd manner; Homme responded physically, landing blows to each man’s head. The men fled the store, and Homme wound up with a bruised knuckle.

The following night at Niagara, Homme was put in a similar situation. “Someone was being extremely rude to my girl and also was trying to get my other friend drunk and [pick her up],” says Homme. “So I told him that wouldn’t be necessary. Then he told Timmy to go fuck himself, then he told me to go fuck myself. He had every chance to leave, but he stepped forward and I put his lights out. And that’s not my fault; I’m not a tough guy. I’m a big person, and I’ve never been a bully. I don’t have a white horse tied up outside or anything, but I have been a protector in a lot of situations. Doesn’t it suck to watch someone get picked on and nobody does anything about it? I hate that. I’m willing to lose. Because somebody has to do that, and apparently, I’m the right size for it.”

The next morning, Homme discovered his swollen fist was unable to hold a drumstick, forcing the Eagles to cancel their scheduled show in Philadelphia that night. The New York Post later reports Homme “had words with a guy at the bar and ended up taking several punches.” Homme, who’s very aware his recent brawls suggest he’s a hypocrite for admonishing Oliveri’s violent behavior, is pleased with the paper’s mistake: “I would rather have them say that.”

***

Some people go out to the desert looking for peace and quiet, only to find there’s a constant, low hum—a nearly subsonic vibration of the Earth—that drives them mad. Others seek to be humbled by its geography; if you want to feel like an ant, the flat, yawning landscape and unforgiving heat will show you just how small and vulnerable you are. Those looking for drugs will find a veritable open-air market of crystal meth. Every once in a while, some enterprising New Yorkers arrive and open a shop or restaurant, only to find out there are no customers here.

There are also the people who come out to Joshua Tree because Josh Homme asks them to. Since 1997, Homme has been summoning musicians to Rancho De La Luna for impromptu writing and recording spurts dubbed the Desert Sessions. Though the Desert Sessions can be a proving ground for Queens songs, the gatherings have taken on a life of their own as a sort of desert-rock summer camp and a more modern pursuit of cosmic American music. Roughly 30 artists have passed through Rancho De La Luna so far, with Polly Harvey and Dean Ween, among others, appearing on last year’s Desert Sessions 9 & 10. Despite appearances, Homme insists he’s more ranch hand than boss man. He prefers to be compared to Mike Patton (the Ipecac Records ringleader) than P. Diddy (a studio svengali).

“No one’s asking me, really, so I’m asking other people,” says Homme. “I think there’s a misconception that it’s me saying, ‘Hey, you.’ It’s more like, ‘Do you wanna?’ If someone from the outside is watching and they think I’m like, ‘Hey, let me bring you into the circle,’ that’s so lame. I’d hate to even be attached to that. Sometimes I’m the shepherd of the weird. You should hear what the flock sounds like: daaaa-daaaaaa-blaahha-wwwaaahhh. Lots of crayons.”

Whatever charge he’s leading—Queens, Eagles or Desert Sessions—Homme does seem to surround himself with a cast of odd, eccentric characters. To put it in junior-high terms, there have been outsiders (Lanegan), rejects (Hughes) and psychos (Oliveri) in the ranks. “That’s where all the good music comes from,” says Homme. “They’re more fun. I would say I’m probably pretty normal. Either that or weird enough to not know. I would also say that it unfairly suggests I’m the shepherd and everyone else is the flock. It’s more like shepherd school, where everyone is learning to be a shepherd.”

***

A time capsule arrives on Rancho De La Luna’s doorstep bearing Homme’s name and the date March 11, 2002. It’s a gift from beyond the grave, sent by Rancho De La Luna founder and original owner Fred Drake, who died of cancer two years ago. Before Drake’s death, Homme had asked him to gather any tapes of Queens/Desert Sessions material he had lying around and pack them up for safekeeping. A friend delivered the package this morning.

“This is dated about a week before Fred died,” says Homme. “He wrote, ‘You’ll get this when you get it. I thought you might want this, but thought you might need to wait for it.’ It’s just like Fred to make me wait two years for this.”

Drake’s recording studio is currently run by a committee of local associates, most notably Earthlings? singer/guitarist and erstwhile Queen Dave Catching. When not hosting Homme-related sessions, Rancho is an oasis for other musicians—Daniel Lanois, Fu Manchu and Victoria Williams, who lives a mile up the road—looking to soak in the desert-homestead vibe. But this week, the studio belongs to the gang— from Big Al to Little Timmy—and seven days’ worth of writing and preproduction for the next Queens Of The Stone Age album, due later this year.

“This is about to be the best Queens record ever,” says Homme, who has 23 songs ready to record. “I feel like right now is a great time for us to dip back into the mystery and the darkness a little bit. There are moments where it sounds like the brothers Grimm.”

To dispel a few rumors that have been flying around the Internet, Alain Johannes, though present on the new recordings, isn’t Oliveri’s replacement on bass. “I haven’t even begun to look (for a new bassist), to be honest,” says Homme. “It’s something that’s delicate. It’s not really about filling shoes; it’s almost about getting new shoes.”

Contrary to what was reported by the NME in May, the Disneyland Marching Band will not appear on the upcoming Queens album. Well, not really. “I was fucking around,” says Homme. “It was something that was funny to say to English people … We are having certain sections of one of the marching bands, but they’ll have a different name.”

And this, at last, is where we come full circle—traveling around the moon, you might say—to “Dick Balls.” The zen joke, the meaningful meaninglessness, the imperative nothing, the sound of six men playing music in the desert to the delight of nobody but themselves.

“How do you make music the most important thing possible?” asks Homme. “By not making it that important. This is probably a really, really important record for Queens. With Nick gone, for some people it’s like we’ve got something to prove. To be honest, I thrive on that situation, anyway. Even if the record isn’t good, what am I gonna do?”

Homme’s rhetorical question doesn’t resound. It kind of drifts out into the desert air and gets lost in the illogic of it all. Homme knows exactly what he’s going to do and how he wants to be remembered.

“I’d love for people to be able to tell within five seconds that it’s me,” he continues. “That’s all I really want. It seems like there’s a book somewhere about people who do it for the respect and for the right reasons—some kind of noble, pretentious-bullshit book—but that’s the one I want to be in.”