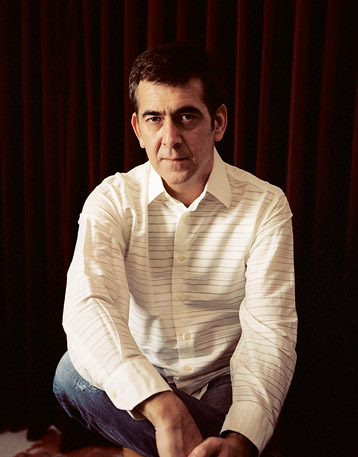

In a 1998 MAGNET interview, a somewhat frustrated Tommy Keene threw a scare into a small but slavishly devoted cult of power-pop enthusiasts by suggesting his then-current album, Isolation Party, might be his last. Thankfully, the prediction proved premature. Since then, he’s released a live record (2001’s Showtunes), another studio effort (2002’s The Merry-Go-Round Broke Down) and a rarities disc (2004’s Drowning), all to the kind of critical acclaim and commercial neglect that Keene has grudgingly come to accept over the course of a three-decade career. At age 47, Keene has just released his best work in a decade with Crashing The Ether (Eleven Thirty). Recorded at his Los Angeles home studio, Ether finds Keene producing and playing almost every instrument, yielding an album that recalls the twin peaks of his classic ’80s LPs: 1986’s Songs From The Film and 1989’s Based On Happy Times. The sessions that produced Crashing The Ether also found Keene simultaneously cutting tracks for a collaborative record with erstwhile Guided By Voices leader Robert Pollard. The duo’s disc—with Keene composing the music and Pollard adding lyrics and vocals—is set to be released under the Keene Brothers moniker this summer. Currently, Keene is touring as guitarist/keyboardist in Pollard’s solo band. It’s another plum gig for Keene, who’s previously handled similar chores for Paul Westerberg and Velvet Crush.

You’re a huge Bruce Springsteen fan, though people probably wouldn’t guess that from the kind of music you play. But there seems to be a little bit of that influence creeping in on Crashing The Ether.

A little bit of Bruce always seeps in. For example, the lead break in “Driving Down The Road In My Mind” is a total Springsteen-style bombastic arena solo. But I’m so far away from him vocally and personally, in terms of how he grew up. I’m not a working-class guy from Jersey, I’m a middle-class suburban kid from Maryland. But yeah, I’ve seen him like 40 times.

You also have a connection because you were friends with Nils Lofgren’s younger brother, right?

Yep, we played in a band together. He was a year older than me in junior high school. I used to go see Nils’ group, Grin, a lot back then. In fact, Nils was really a huge influence on my guitar style and my songwriting. When people ask my influences, I always say the Beatles, Who and Stones, but I think the people that influenced me the most were the people I came into contact with when I was learning how to play. Nils’ brother Mike basically showed me how to play guitar.

The way your career took shape was almost accidental, wasn’t it? Because you were really a band guy and sideman playing in New York in the early ’80s, then you suddenly became a solo artist.

After I was in New York, I moved back to D.C. I didn’t know a Peter Holsapple—a lead-singer type—or another songwriter who I thought I could get a band together with. So I thought, “Why don’t I do a solo thing? I have a kind of different, distinctive voice. Maybe it’ll work.” I was thinking of it almost as a gimmick. But I didn’t think I’d be doing it 25 years later. [Laughs] I always figured I’d put out a solo record and then join a band, but it never happened. If there would’ve been a Michael Stipe character, or if I’d found my Roger Daltrey, I would’ve joined up with them.

Has being gay been at all problematic, particularly given your status in the power-pop world?

Well, the power-pop world is probably a little more accepting than the drop-D metal world. But no, it really hasn’t caused a problem. Occasionally, I get a little tired of tit jokes in the van. But hey, I like tits, too. [Laughs] Seriously, though, it probably hasn’t been a big deal because I haven’t sold a lot of records. If I sold a bunch of records, maybe people would care. If I were someone like Michael Stipe or Tom Cruise, it might be an issue. [Laughs] I don’t mean to be flippant, but it’s never been any kind of thing for me.

Your music-industry experiences are the stuff of legend. Basically, you kind of had the rug pulled out from under you in pretty spectacular fashion a number of times. Any regrets?

You know, when I got my group together, I was 23. By the time I got offered a deal, I was 26. We’d made a record with T-Bone Burnett and Don Dixon that was never released. Basically, Geffen came along and said, “If you put that record out, the deal is off.” I didn’t, and that was the biggest mistake I ever made. But when you’re 26 and someone’s dangling this Holy Grail major-label contract in front of you, you think, “This is my only chance. I’ve got to take it, even if these people don’t know what the fuck they’re doing.”

But being with Geffen gave you some neat opportunities. You made Songs From The Film at George Martin’s AIR studios. For a Beatles fan, that must’ve been a dream come true.

Yeah, but the results weren’t all that great in the end. It’s funny, at the time, George Martin got mad because I said something in Rolling Stone about how it was an impractical place to record. But I just meant that for a group at our level it was a little too extravagant. The people who recorded there were Paul McCartney, Elton John, Dire Straits: superstars that would bring their entourage. Meanwhile, we’re a little indie band—two guitars, bass and drums—so it was a bit over the top. We didn’t think of the repercussions of the massive bill we were racking up. We were too busy thinking, “We’re recording a platinum album!” [Laughs]

And, of course, you did get to act alongside Anthony Michael Hall at the peak of his powers (in 1986 drama Out Of Bounds).

Geffen was going to do the soundtrack, and there were parts for two bands in the film. They already had Siouxsie And The Banshees, and they wanted someone else. The two people it came down to were me and Chris Isaak. So we sent them a demo of the song “Run Now,” and the director really liked it because it fit the part in the movie where Anthony Michael Hall was being chased through a club. So, somehow, I ended up getting the gig over Chris Isaak. I was on the set for two long days. Anthony Michael Hall actually brushes past me in the scene, and I jump out of the way. That was my acting debut—overacting, I should say. A couple months later, we were back in L.A. filming the video for “Places That Are Gone,” and my brother and I ran into Anthony Michael Hall at a 7-Eleven—and he was with Siouxsie Sioux. They’d just done their scene, and she was in full makeup and carrying a cane and everything. Anthony was like, “Tommy, man, I’ve got this house. You gotta come up. We’re having a party.” I think Siouxsie was buying him a bunch of beer, because he was probably underage. So my brother and I went way on top of Laurel Canyon near Wonderland Avenue, and it was Siouxsie, Budgie (Banshees drummer) and a couple actor friends of Anthony Michael Hall’s, one whom I’m pretty sure was in Weird Science with him. Siouxsie and everyone were doing drugs off in another room. There was no stereo in the house, but we had a rental car, so Anthony said, “Tommy, pull your car into the garage and I’ll leave the door open and play my cassettes and we’ll turn it up real loud.” I remember him playing Led Zeppelin’s Coda. [Laughs] After about 30 minutes, I was like, “Well, I think we’re gonna head out now.”

(1993’s) The Real Underground is one of the better odds-and-sods compilations out there. I notice you’re still selling copies on your Web site.

When (former label) Alias Records folded five or six years ago, they ended up with two guys left running the mail-order department and dealing with whatever stock they had left. I called and asked how many of The Real Underground they had left. They said, “We have a few and will sell them to you for $1.20 apiece.” So I bought up the remaining stock. But what I never knew was that record companies, because of tax reasons, when they have product lying around that hasn’t sold after a certain period of time, they have to physically destroy all the copies. The Alias guy was telling me about this because the label had signed all these bands and pressed up 10,000 records and sold 300 copies. So these guys were literally spending all day at a huge trash compactor, crushing the remaining 9,700 records. That was one of their jobs. [Laughs]

You’ve obviously had some weird breaks in the business, but you don’t seem bitter at all.

I certainly hope not. I’m 47, and I just feel lucky that I’m still doing it. I’ve worked with the guys I consider the two best songwriters of my generation in Bob Pollard and Paul Westerberg. And people are still eager to put my records out. It’s all a gift. It could be a lot worse.

—Bob Mehr