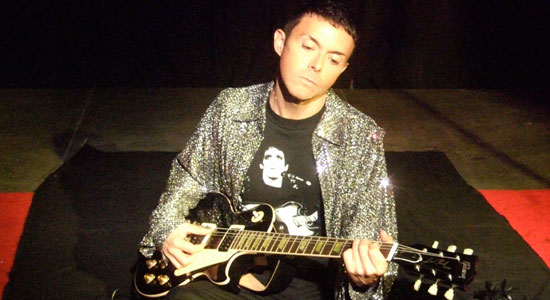

Fronted by the nervous guitar and earnest vocals of Richard Barone, the Bongos grabbed the torch from the Talking Heads to light the way into the 1980s for a second generation of eye-opening New York bands that sounded nothing like their predecessors. Dedicated to the proposition that the tired and huddled masses could still find comfort at CBGB (or at Maxwell’s across the Hudson River), the Bongos ruled the greater-NYC roost. A stimulating succession of solo releases, topped by this year’s Glow (Bar/None), leaves no doubt that Barone is still hitting on all cylinders, a vital and imaginative force in today’s music scene when most of his contemporaries have fallen by the wayside. Barone will be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week.

“Gravity’s Pull” (download):

https://magnetmagazine.com/audio/GravitysPull.mp3

MAGNET: I hear a lot of background noise, like somebody moving heavy furniture around.

Barone: I’m at the gym, actually. I do it just about every day, whatever time I can. If you hear a loud banging it’s just the sound of being at the gym. Especially when I’m working with Mick Rock, the photographer, I have to work out all the time, because he has me strip in almost every picture. I’m in his new book, and he’s like my favorite photographer. I know his work from Bowie and Lou Reed, especially.

A good photographer is like finding a good dentist. I got out my old copy of your 1990 solo album Primal Dream today, which I haven’t played in a while. Who did the orchestration for that record?

To be honest, I did most of the orchestration on that album. I studied music in college, but my music training came mostly from scoring films.

I’ve always thought your music was a natural for movies. Have you had a lot of stuff in films?

Not really, but for this album the label is really going for that. I have friends who are film directors. And I have had indie films use some songs here and there. My songs with Jill Sobule made it into a lot of television shows.

Something you wrote with Jill for the new album, “Odd Girl Out,” is the best song I’ve heard this year.

Oh, thank you. I think we’re going to do a video for that one. I like writing with Jill. All my writing partners, each one is so different. And hers has this storytelling feel to it, like an old-fashioned kind of folk song. We wrote that line by line. With her it’s very conversational. The drums are playing in unison with the drum loop on that, and it’s such a cool sound. It sounds like two drum kits, one on each side. The drummer on the choruses plays a big drum kit and on the verses play a small drum kit.

I’ve always liked records with two drummers. It makes the percussion sound fatter when they don’t quite land on the same beat.

It expands it, it really does.

I don’t usually ask technical music questions, but this digital Gibson Les Paul guitar you have with a dedicated recording track for each string sounds really interesting.

Right, on the song “Glow” you can very much hear it. Normally, it’s one guitar that becomes one big mass of sound. But if you have each individual string on its own track, then you can put them around the stereo speakers so that each string has its own placement. That’s why I love the digital, and I use it live also. It was in development for 10 years, but I think there have only been a handful that have been manufactured, and I happen to have two of them. I’m the only artist I know who plays one of those. The sound is very accurate, and you can put a different effect on each string.

What would really sound cool would be an electric 12-string with that same technology. Anybody done that yet?

Not yet. This is still so new, but if I really wanted to, I could suggest they make a 12-string version of this.

I’ve always loved the 12-string sound, beginning with the Byrds.

Oh, me too. Speaking of the Byrds, I’ve been working with Pete Seeger. It’s still going on. I wanted him to perform at a benefit concert for the oil spill cleanup in the Gulf of Mexico. He’d just written a song that referred to the oil spill. He was on the ball there. I hadn’t really heard a song that talked about it yet. He started singing it to me on the phone, and I just loved it. It was so pure and simple, like a sing-along. So I said, “Pete, why don’t we record it?” And he agreed to do it. Then at the last moment he told me he wanted to record it on the sloop Clearwater.

That’s Pete’s boat?

It’s his boat, and it’s a symbol of his 1969 campaign to clean up the pollution in the Hudson River, which was a mess. He didn’t tell me this, but it’s obvious he wanted to record this song on that same boat. So we brought a mobile recording system with incredible microphones and captured it. It’s so crisp, you won’t believe how well it came out. It sounds like a modern recording and he’s 91 years old. It sounds like a brand new artist just making a record while he’s sailing up the Hudson. We filmed it with several cameras, too.

This’ll come out on a Pete album, or a Pete-and-you album?

You know what, I’m just the conduit here. I’m just letting him be Pete. He had singers he wanted to be on the boat with him, and I was just there to capture it. I was the facilitator. As much as I’m a recording artist, I’m also a producer. It’s just as interesting for me to create the recording, not just be in it. I don’t always write myself into the script. I love working with other artists and I collaborate with so many. Sometimes I’m in the group and I play, but other times I just like to be the ears. I worked on the arrangements. We added some instruments. It was a real production for him.

Are you familiar with an old friend of mine, Robert Schneider of the Apples In Stereo? I sense a similarity in musical passion and drive between you two.

I am; he’s a great guy. I met him at a concert that I was doing about a year ago. He came over and introduced himself. We became good friends. We’re talking about writing some songs together for one of our next projects.

The sparks should fly on that one.

I’m trying to get that scheduled. You know, Glow, the current album, will be continued with the next installment.

I liked “The Glow Symphony.” It’s kind of a Brian Wilson thing.

Thank you. The label has been very good to me. Glenn Morrow, who signed me to Bar/None Records, was my first roommate in the area.

He was in the first version of your pre-Bongos band, A?

Yeah, the letter A. We never really recorded too much, but we’ve always talked about it. This is our first chance to do something together. I gave him 20 songs, and he picked the 11 that are on the album. He suggested we do an instrumental version of “Glow” and I said, “Of course, absolutely, let’s do it.” But we couldn’t figure out what to make the lead instrument. So, at the last minute we decided to use the Stylophone, a very obscure ’70s instrument that’s played with a sylus. You play it with a pen. It’s the same thing that David Bowie used on “Space Oddity.” It has a flat keyboard, but there’s no delineation between the notes. There are just lines to show you where the notes would be. It’s pretty nice. (Album producer) Tony Visconti got this one for me, a 1973 model with different effects. For years it was the most obscure instrument, and now you can buy them at Urban Outfitters. I guess it’s getting into the mass culture again. Born in 1969 and it disappeared for 40 years. But it’s back.

That’s funny because I just interviewed a guy who played the autoharp, a pretty obscure, homespun kind of instrument nowadays.

Yeah, with the buttons. There was a time when some of the instruments they made were just for the people and the autoharp was one. The Stylophone was designed for people to play along at home to records.

How about a little background, Richard? I know you grew up in Tampa, Fla., as something of a musical prodigy, playing the guitar at age seven.

I don’t know if I was a prodigy. I’ve always played by ear. Let me put it this way: I make my way around a melody. But the reason I got into music at age seven was that I already had my own radio show on a commercial radio station.

Well, how did that happen? Aside from Mozart, that’s not every seven-year-old kid’s gig.

I was obsessed with pop radio at that age. They were broadcasting from the beach, and my family was there. I went up to the DJ and said, “I can do that.” And he said, “OK, I’ll put you on the air.” And he did. So, l announced the next record, I think it was Donovan. The next thing you know, people started calling in who really liked the way I did it. He told me to stick around, and I ended up having my own show every Sunday. My moniker on the air was “The Littlest DJ.” I really enjoyed it and they gave me every pop record of that period. So, I got very serious about music.

Tell me about how you wound up producing Tiny Tim?

I recorded Tiny Tim in the ’70s when I was 16 years old, a collection called I’ve Never Seen A Straight Banana. He took me seriously and wanted me to put the album out, but at that time I was in high school. So that Tiny Tim album stayed on the shelf until I moved to New York when I was 18 and got signed to RCA. I finally got to finish that project just last year.

So, how did you make it from Tampa to New York?

I came to New York because I met the Monkees. They were on tour and their backing band, the Laughing Dogs, were from the CBGB scene. When I spotted them at the Monkees show I knew the band because I’d heard them on the Live At CBGB double album. So we met and hung out, and they said, “We’re on the road for the rest of the year. Why don’t you stay in our loft in Brooklyn?” This girl Jean and I wanted to get out of Tampa, so we did.

That must have been a serious case of culture shock.

I got on a soap opera, As The World Turns, for a while.

And what was the name of your character?

[Reluctantly] I played a boy named Eric.

And what was Eric’s problem? C’mon.

[Laughs] Well, probably they were very similar to my own, actually. But anyway, I walked off that show when the Bongos, who’d only been together for a few months at that point, got signed to a British label called Fetish. And we got sent off to London in 1981 to make our first album and play at the Rainbow Theatre. It was a very trendy kind of scene, and we played the Cabaret Futura which was where Depeche Mode was playing. We stayed in London for about a year and toured Germany, France and Holland from there. And that’s where we did most of Drums Along The Hudson on a sheep farm in Surrey.

So how did you wind up down south in Surrey?

The label had a deal with John Foxx of Ultravox, and he had this beautiful studio that was on a sheep farm. So they arranged for us to record there, at Jacob’s Studio. It was very comfortable and I was extremely spoiled. When I came back to New York to make our next record, I expected to have that kitchen staff on duty and be able to go out for a walk on the farm that did not exist on 36th Street. We didn’t know what we were doing, of course, but we ran the American division of Fetish. We had to do it ourselves.

How did you get signed to RCA?

The first album came out on singles over here and finally wound up as a compilation on PVC. At that point, RCA began courting us. And other majors, too, but we chose RCA for some reason. They were the most into it. They came to our rehearsals. We felt comfortable with RCA.

Tell me how the Bongos’ sound came about. It seemed to be sort of this new, nervous sound that paired up well with other newer bands like the Feelies or the Individuals.

I think we knew the decade was turning, and we were on the cusp of a new sound. And we didn’t want to copy anybody. We were very conscious of not doing that, even though we loved Talking Heads and the Ramones and would go to all their shows. My thinking was this: to find out what each musician really likes. Rob Norris, the bass player, really was into surf music and really liked the Ventures. And I really liked the British kind of glam sound: T.Rex. I loved that chunky guitar. And the drummer, Frank Giannini, really liked pop songs like ABBA with big harmonies. Rob also liked Creedence Clearwater Revival, so we kinda combined all these things into making our own sound. The Bongos rarely rehearsed. It was very pure. I’d write the songs, we’d do them once or twice, then start doing them onstage. And that’s why I’m still a known collaborator, because the only way to get a new sound is to bring out what each musician really likes.

—Jud Cost