Each week, we take a look at some obscure or overlooked entries in the catalogs of music’s big names. MAGNET’s Bryan Bierman focuses on an album that, for whatever reason, slipped through the cracks in favor of its more popular siblings. Whether it’s new to you or just needs a revisit, we’ll highlight the Hidden Gems that reveal the bigger picture of our favorite artists.

“Bob was really hitting the bottle that weekend. That was a terrible fuckin’ weekend. There was a lot of stuff that makes Hard Rain an extraordinary snapshot—like a punk record or something. It’s got such energy and such anger.” —Rob Stoner

Is there really anything left to say about Bob Dylan? His life, his music, his words have been prodded and dissected in every way imaginable; proving, at least to whomever is doing the investigating, any theory or interpretation that enters the mind. Artists create and the audience enjoys it, all the while trying to figure out what it “really means”—it’s a tradition as old as man and, especially in Dylan’s case, one that will continue for generations to come. But to convince yourself that you know the man because you studied his songs or read a dozen books on him is, ultimately, a foolish state of mind.

I started thinking about this as I prepared for this piece. I don’t pretend to know Bob Dylan any more than you do, or any more than the authors of the numerous books and articles I’ve researched do. These are works by people who, for the most part, don’t know Dylan personally. Even though there might be interviews with people who do know him, people who were around him during whatever period they are being asked about, that’s only their view of the events. And without delving into a philosophical discussion, it’s entirely possible that Dylan doesn’t know himself any more than you or I know ourselves—and if that’s true, then we really don’t know shit about Bob Dylan.

I only emphasize this, as it made me wonder about my role as part of the audience. Usually in these columns, I spend the first half giving the historical or biographical perspective surrounding the album, then use the second half to focus on the actual music. Without fail, I will eventually come to a point in the midst of writing where I worry to myself, “Is there too much historical background here? Will anyone really care about this part?” Though there perhaps probably is too much backstory in these articles, I’ve always been fascinated in the stories behind the work. For me, knowing where an artist was at during an album’s creation, or the personal or professional struggles they were going through at the time, will often give the work more meaning.

But lately, I’ve been wondering if that’s fair. Shouldn’t a work of art be judged solely on what it is and nothing more? It might be wrong to let outside influences affect your ability to enjoy something. However, as much as I believe the previous statements to be true, sometimes getting the full picture does paint works in a different light. Knowing this can ultimately enhance your appreciation for the art, and there’s no better example of this than Bob Dylan’s Hard Rain. Generally viewed as an unimportant and mediocre live album (which is partly true), it’s also the soundtrack of a man who’s exhausted, frustrated and futilely trying to hold together his broken marriage. But instead of succumbing to all the craziness around him, Dylan keeps his head above water by doing what he always did: using it to inspire his music.

The idea for what would come to be known as the Rolling Thunder Revue started in mid-1975, as Dylan recorded his next album, Desire, the follow-up to what many consider his greatest work, Blood On The Tracks. Though there were dozens of musicians used during recording sessions, the core band on Desire featured Rob Stoner on bass, Howie Wyeth on drums and piano, and violinist Scarlet Rivera, who Dylan literally met on the street and asked to perform with him. After the album was fully recorded, Dylan kept the trio around and asked them to jam with him for a few days. Though they didn’t know it, the group was being rehearsed for an upcoming tour. These rehearsals also included musicians T Bone Burnett, David Mansfield and Steven Soles, as well as a few of Dylan’s old friends, Joan Baez and Roger McGuinn, all of whom would join Dylan in a few weeks for a nationwide tour.

The first leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue began in the fall of ’75, featuring even more guests—ex-Spider From Mars Mick Ronson, Bob Neuwirth, actress Ronee Blakley, Allen Ginsberg—as well as anyone else who showed up, including Joni Mitchell, who performed a few shows. The concerts combined the various styles of all the players performing a large catalog of old favorites, newer songs, plus some standard folk tunes, and the gypsy communal style that spirited the tour led to some of the strongest performances of Dylan’s career. When they weren’t playing to packed crowds, the gang, along with Dylan’s wife Sara, was filming Renaldo & Clara, Dylan’s surreal movie, which was part documentary, part concert film and part autobiographical love story, which was later released in ’78. Everyone, from the musicians to the audiences, had a blast and after the tour ended, Desire was released to rave reviews, giving Dylan his second number-one album in a row.

In hindsight, they probably should have counted their blessings and left it at that. Dylan’s relationship with Sara had been unfolding for some time, inspiring his best songs during this period, as well as the core of Renaldo & Clara. Perhaps running away from the inevitable dissolution, Dylan decided to gather the troops back up for another leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue, a decision that would prove almost disastrous.

In April ’76, the tour began its journey across the Gulf Coast, but the celebratory spirit of the ’75 shows was not there. For starters, the band was booked into large stadiums and along with bad management, ticket sales were poor, forcing some shows to relocate to smaller locations or be cancelled outright. It was also hurricane season in the Gulf, leading to numerous shows being rained out. This gave the band nothing to do except drink and consume their new drug of choice, cocaine. Perhaps worst of all was Dylan’s frazzled state of mind at the time. With his family falling apart and piecing together what was left of a tour, his head was in another place, falling into a depression fueled with drug use and his various mistresses.

Having filmed a previous concert for a planned television special but disliking the results, Dylan was forced to pay for another concert shoot to replace it. The show that they settled on was near the end of the tour in Fort Collins, Colo. The show would also be recorded for a live album, but the band also recorded an earlier show in Fort Worth, Texas, which would also appear on the record. Unfortunately, when they finally arrived in Colorado, they were right in the middle of a week-long downpour. Each night, the concert was forced to be postponed because of the storm, which was costing Dylan a lot of money to keep the film and sound crew around. If this wasn’t enough, Sara showed up on tour and the couple spent most of their time arguing. On the third night, May 23, 1976, Dylan and the band decided to just stick it out, performing to 25,000 soaking-wet fans. Said Rob Stoner, “Everybody’s soaked, the canopy’s leaking, the musicians are getting shocks from the water onstage. The instruments are going out of tune because of the humidity. It was awful. So everybody is playing and singing for their lives, and that is the spirit you hear on that record.”

Hard Rain opens with a sloppy but energetic reworking of “Maggie’s Farm.” Dylan’s voice on the Rolling Thunder tours is vastly different from his previous work, especially his country albums, using a guttural yell, leaping over the double drums and fiery guitar work of Ronson. This ragged sound appears all over the record and the expansive mix is very rhythm heavy, especially “Stuck Inside Of Mobile,” with its driving backbeat.

The highlight of the record and film is the venomous version of “Idiot Wind.” Most likely written about his failing relationship with Sara, Dylan’s voice cuts even deeper than the original. In the film, you can see the pain on Dylan’s face as he admonishes himself, as well as Sara, who is standing off the side of the stage. Dylan glances at her throughout the performance, pouring his heart out as if there was no one else around. There’s a vitriolic hilt in his voice as he proclaims, “I’ve been double-crossed now for the very last time, and I think I finally see.” It’s a chilling performance of one of the man’s greatest songs.

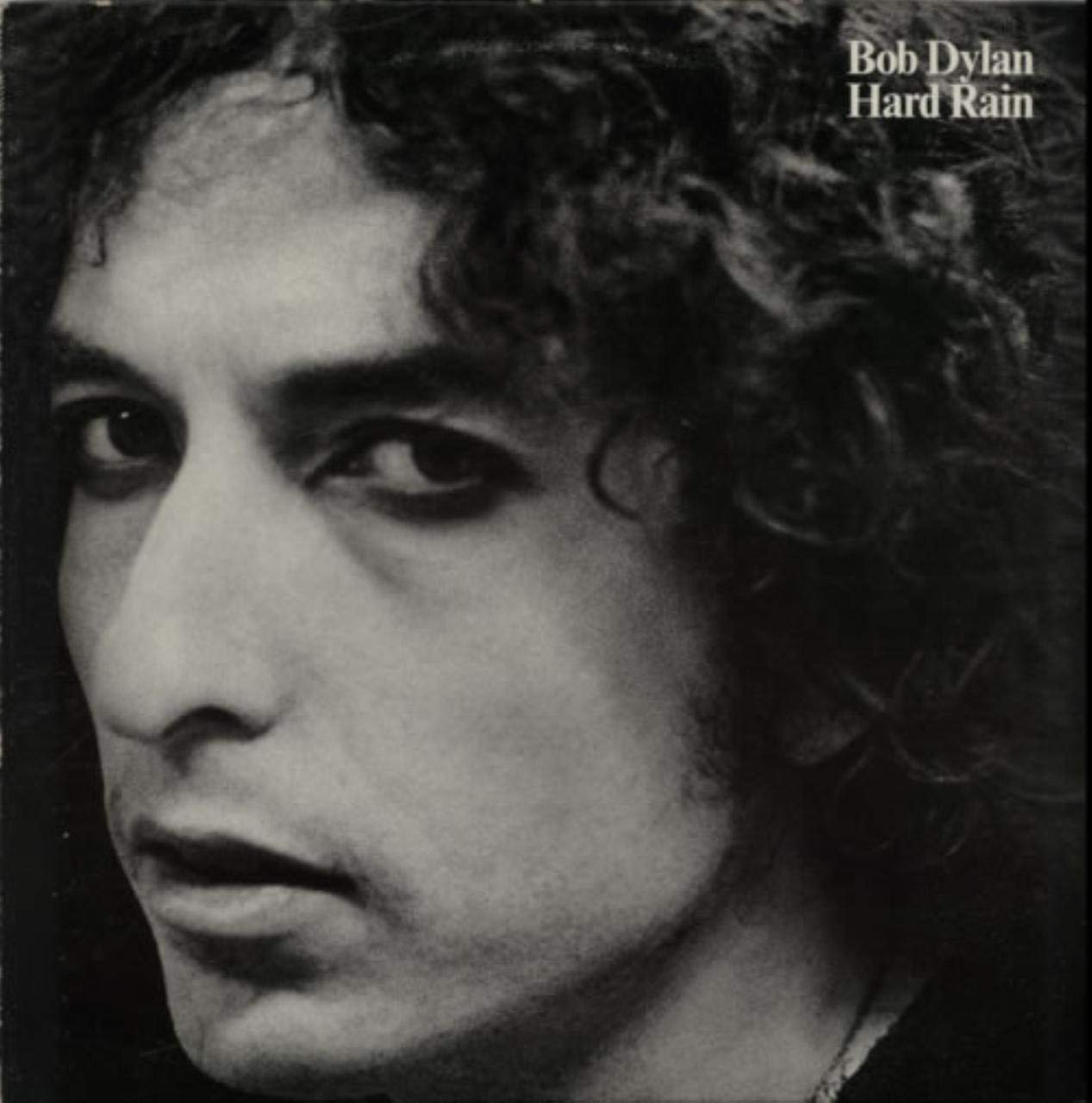

The concert film and album were appropriately titled Hard Rain, both released later that September. Airing on NBC, then later on Japanese television, its reviews were poor, as were ratings and album sales. The film has never been issued on home video and the album’s legacy will most likely remain mixed at best. (Those interested in the first part of Rolling Thunder, should get The Bootleg Series Vol. 5 double album, released in 2002.)

At times, Hard Rain sounds bloated, featuring performances that are sometimes too ragged; though knowing the subtext of the events, some moments feel triumphant: musical and personal. We may not know Bob Dylan, but it’s an awfully close look at a stranger.

3 replies on “Hidden Gems: Bob Dylan’s “Hard Rain””

I’ve always loved this record, and the video is cool if you can find it. I remember camping on a mountain in Virginia with friends, really high on magic mushrooms listening to Hard Rain.

It was as if Dylan was standing on a tower with the world at his command. Cosmic stuff!

One of my favourite Dylan records, and I remember watching when it aired in ’76. Dylan was even on the cover of TV Guide that week. The album is finally getting the remastered treatment in the upcoming complete Dylan box set; now, the video portion needs an official DVD release, it’s long overdue.

Bloated my ass. That album rocks. I had it on cassette many years ago. The arrangements and musicians are total pedal to the metal. PLEASE RELEASE IT ON CD.