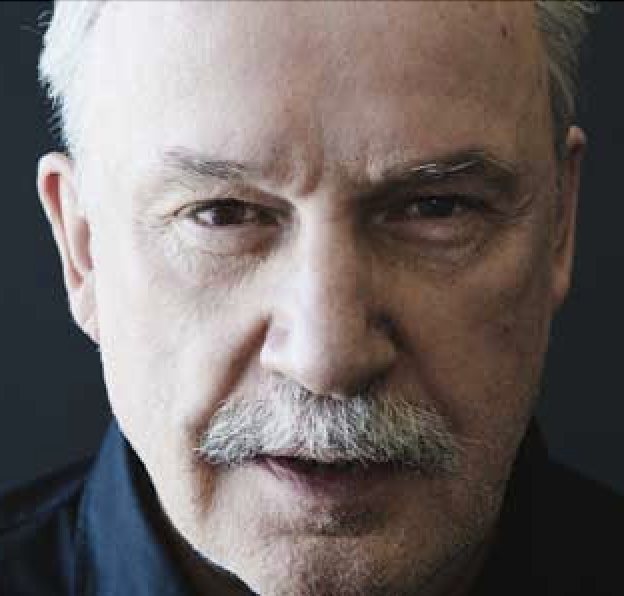

Giorgio Moroder is dance music. Long before Daft Punk lionized the disco king with “Giorgio By Moroder” on Random Access Memories, the producer/composer created the hypnotically repetitive ’70s electro-disco canon, first (and best) with Donna Summer before doing likewise for artists such as Berlin, Sparks, Queen and Irene Cara, then on his own grooving solo albums. When disco passed from fashion, he brought his syncopated skills to film scores for Midnight Express and American Gigolo before (mostly) retiring by the late ’80s. Now, at age 75, he’s back in the game with Déjà Vu, a rousing EDM-based album featuring name-above-the-title dance divas such as Britney, Kylie and Sia.

I know at your start that you played in jazz combos and rock bands in lounges throughout Switzerland. I can’t picture you doing that. Were you ever much of a band guy?

No. I would not think so. I mean, it was fun being 27 or so doing that with a bassist and a drummer, doing a Beatles song and such, but I knew …

Knew that being a producer would be more your speed?

Yes, actually, that’s right about it. I wanted to promote my own stuff. I had some money put aside so that I could survive the first years of that. Getting a hold of an early synthesizer convinced me of such.

So, when did you hear these new songs in your head?

Very recently. I was retired, you know. I did some composition for one of the Olympics, but I was out of the game. I did dip a toe in doing some DJ work, and then came the Daft Punk success. That really spurred me on. Changed my mind. I thought a modern dance record with some retro—disco—could work. I didn’t want to rely on the past.

So, you had to psyche yourself into making music again through DJing?

You know what—a little. Ten, 15 years ago, I got asked so often to DJ, but I turned everyone down by saying, “I’m a producer.” Now, it’s nothing like the old days, nothing like I imagined. By the way, I think I was one of the first DJs ever. In 1969, I performed as a DJ and a singer at a little club in Germany. I became part of a management company: the German DJ Association.

I think that was one of Kraftwerk’s earliest names. When you started doing disco—with Pete Bellotte, with Donna Summer—did you have a blueprint or did you just wing it on a purely experimental tip?

With Donna, it was an accident, as Pete and I were working on a project and needed women without English accents to sing. We found her. She did a great job. I also said that when I had something great for her that I was going to call her. That was “Love To Love You Baby.”

You’ve worked with male vocalists such as Bowie, Phil Oakey and Freddie Mercury, but mostly you’re all about the ladies: Summer, Irene Cara, Terri Nunn, all the women on this new album like Britney Spears and Kylie Minogue. What about a woman’s voice gets you, works better within the confines of your music?

You know, I don’t know. Maybe it is the sex feeling, the sensuality of the female voice against my melodies. I can’t think of too many guys who can do it. I mean, in the old days, you had the Village People, but … [Laughs] A woman has a more pleasant, sexier sound. They project the image of sexiness better.

In the ’80s, you set aside disco for atmospheric soundtrack work, put aside production for making neon art, left Europe and moved to Manhattan. What were you looking for?

I was looking for the grass that was always greener. I was restless. I wanted to do something else. Plus, disco went through all those problems with the whole “disco is dead” thing. I just kept fading away from music. I had so many other projects: I helped create a car; I did a short movie, which did not work so well.

When you decided that you wanted to do a new project, did the singers come to you? Did you go to them?

It was a mix, really. I had a wish list—my ideal names—and we went from there. Someone such as Sia was at the top of that list.

Do you like the way artists such as Sia or Britney record, piece-by-piece with vocal producers and such? The artists with their own teams, considering that back in the day, an album of yours had one producer in one studio with only your vision and that of the artist to consider?

I’m not a fan of the committee, but it is the way that these things are done now. These artists are very busy with so many different commitments other than music.

Does this mean now that this is how you must operate? Are you competitive in that way, especially since you’ve stayed away from the charts and the business for a while?

I think so. I hope so.

As a producer and a provocateur, do you feel as if you are truly making music differently than you did 30 years ago—or different music than you did 30 years ago? Is it less or more than a series of seductions than in was in the past?

That’s a funny way of looking at it. Yes, it’s very different now. There are so many people involved with each production—co-writers, co-editors—that it is hard to conjure up a seduction. It is not so intimate. It’s changed so much from when it was just me and maybe Pete Bellotte in a studio. There were no such things as vocal producers and executive producers. There was one producer. I am happy the way it is now. You really have to be, as there is no way back.

—A.D. Amorosi