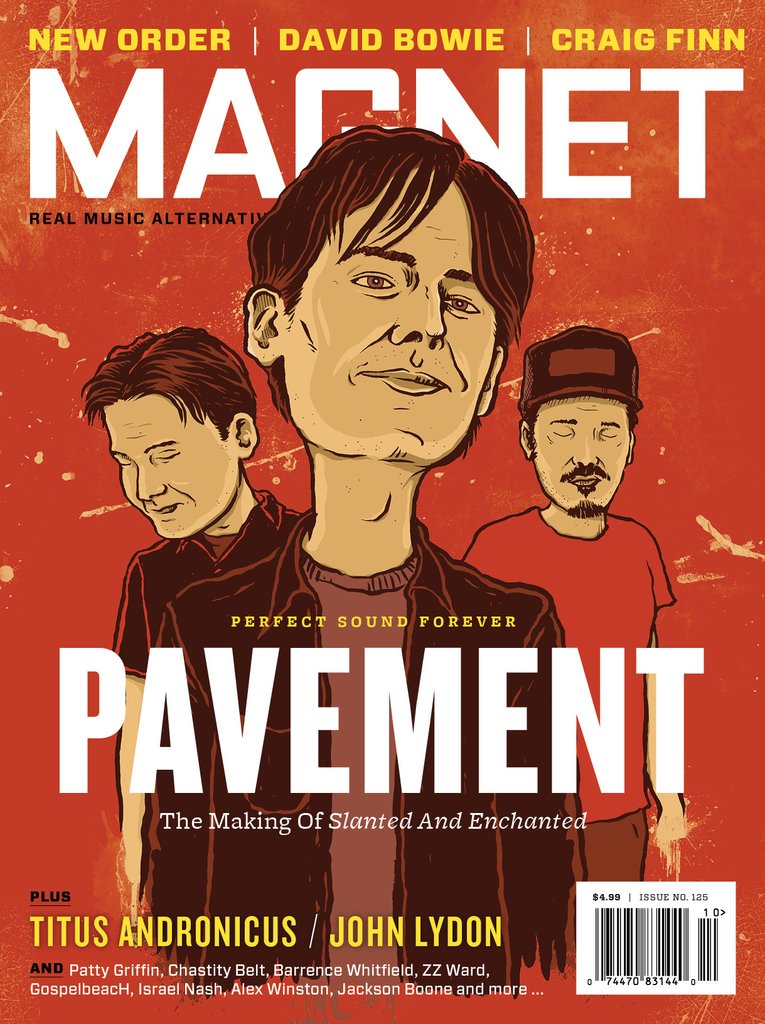

Here’s an exclusive excerpt of the current MAGNET cover story.

When Stephen Malkmus and Scott Kannberg entered Gary Young’s studio to record their first album, Malkmus was cranking out songs, Kannberg was learning the guitar, and Young suspected these kids still didn’t know which end of the fuzzbox to plug into. A week later, they walked out with a record that all but defined 1990’s indie rock. Almost a quarter-century after the release of Slanted And Enchanted, the members of Pavement recall how they made the best album of their—and most everyone else’s—career.

By Eric Waggoner

The music didn’t sound like anything much. That’s what concerned Gary Young about the weird racket the two young guitarists were making in Louder Than You Think, the 16-track studio Young operated out of his Stockton, Calif., home. There wasn’t any weight to it. These kids didn’t even own a bass, for Christ’s sake. They were playing “bass” on detuned guitar. And they hadn’t booked much time in the first place—four hours total at 30 bucks an hour. And that time was passing rapidly.

The sounds coming out of Stephen Malkmus and Scott Kannberg’s amps didn’t really do it for Gary Young on a personal level, either. His own listening tastes ran to intricately structured prog rock—King Crimson, Yes, ELP, Fred Frith, that kind of thing. Part of it was likely the age gap: Young, who was 13 years older than the kids strangling their instruments in his studio this January afternoon, had logged time in a series of Stockton-area bands over two decades. He had a lot of musical experience. This Malkmus guy had some, but Kannberg had very little. Both were rock eggheads, but their source material was rather different from his—hard, angular, static-laced music that began with basic pop forms, but sliced them up into shards.

Young didn’t know Malkmus or Kannberg at all prior to the day they walked into his house. But the hour was waning, and Young’s drum kit was right there in the studio, all miked up and prepped. On the fly, he offered to drum under the duo’s high-frequency guitar lines. They were open to the possibilities of improvisation and experiment already. Malkmus was a free-jazz fan, and Kannberg was so unpracticed on guitar, he hadn’t developed any habits to break. OK, they said to Young, sit down. Let’s see what happens.

The making of Slanted And Enchanted? Ask Gary Young. It’s simple. Rock music is really simple. People overthink it. It’s actually very easy.

“They found me in the phone book,” Young says of how Stephen Malkmus and Scott Kannberg arrived at his studio. The truth is a bit more complicated, but not by much. Malkmus and Kannberg had been classmates at Lodi, Calif.’s Tokay High, one of two high schools that served the Stockton-Lodi area. In 1988, Malkmus received his history degree from UVA; Kannberg, an off-and-on student in urban planning at a Sacramento college, was working at a local record store in Stockton when Malkmus returned to California for a short post-grad stopover. When the two decided to collaborate, the plan was that Pavement would be a studio-only project.

“I asked around the store,” says Kannberg. “Eventually someone said, ‘You should check out Gary Young’s place.’ I hadn’t thought of Gary until then. But when his name came up, I remembered who Gary was.”

And how. Everybody knew Gary Young—at least knew about him. “Gary was a real performer,” says Kannberg. “He was like someone from back in the cabaret days.”

The tales surrounding Young’s substance-fueled act-ups were the stuff of Stockton music-scene legend—legends that often had the uncommon distinction of being true in the smallest bizarre detail. Among several other impressive achievements, Young had once sent his Steinberger bass guitar, a famously ugly, practically indestructible instrument, straight through the plate-glass window of a club and out onto the sidewalk when the band he was in, Death’s Ugly Head, got stiffed by the owner for 60 dollars.

“I hadda do it,” says Young, in the resigned tones of a man who wants you to understand that he was regrettably, upon careful consideration, down to his only remaining option. “This guy, he’s behind me, all ‘Raah raah raaaaah, these fucking punk kids.’ So, yeah, I put it through the window. See, we’re not destructive people. We don’t trash hotel rooms. I just didn’t have a choice.”

Legend aside, Young worked cheap, and he worked fast, and he had an improbable-but-unanimous reputation around Stockton as a wizard engineer. Malkmus and Kannberg entered Louder Than You Think for their four-hour session with a handful of song ideas, but with absolutely nothing in the way of percussion design. Bob Nastanovich—Malkmus’ fellow UVA alum who joined Pavement as a second drummer in August 1990 and would remain in the band until the end—credits Young with much of the rhythmic strangeness that characterized Pavement’s earliest recordings. “Gary was an indie-rock version of Keith Moon,” he says. “He was a dynamo. We were really, really lucky to be associated with him. There were other great bands around at the time, bands similar to us, but Gary was from outer space. He made us unique.”