The Making Of X’s Wild Gift

By A.D. Amorosi

“I play too hard when I ought to go to sleep/Well, they pick on me ’cause I really got the beat/Some people give me the creeps/Every other week, I need a new address/Landlord, landlord, landlord cleaning up the mess/Our whole fucking life is a wreck/We’re desperate, get used to it … It’s kiss or kill” —“We’re Desperate”

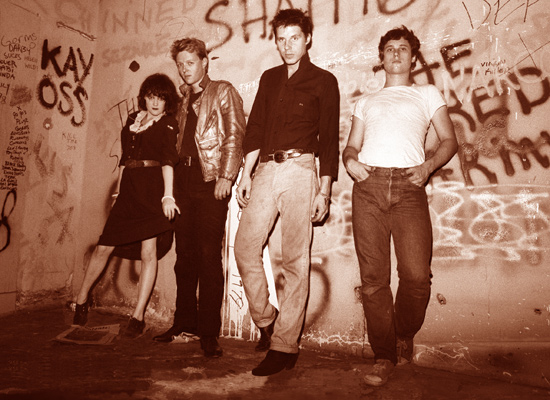

In april 1980, X was on top of the world. After having started in 1977 amid a sympathetic sea of like-minded Los Angeles acts with bassist/singer/poet John Doe, his (then) girlfriend, fellow wordsmith Exene Cervenka, and smiling rockabilly guitarist Billy Zoom (drummer DJ Bonebrake joined after leaving local punks Eyes), the quartet broke out of punk’s pack and quickly rose to the top.

“It was bands like the Avengers and the Weirdos,” says Doe of his immediate contemporaries. “That’s where we came from.”

“For our band to survive long enough for me to afford my own apartment—that’s what I was thinking right then in 1980,” says the typically dry Zoom from his L.A. home office, where he’s preparing for this month’s X tour of America while going through chemotherapy for bladder and prostate cancer. (“So far, so good,” he says of his present health.)

Following the release of 1978’s Dangerhouse label single, “Adult Books”/“We’re Desperate,” the publicly and critically lauded X hooked up with magazine-turned-record label Slash and legendary keyboardist-turned-producer Ray Manzarek to record its menacing, diverse, off-beat album debut, Los Angeles, in 1980. “It was a great time for music and shows,” says Cervenka. “The whole thing. We were in the middle of all that.”

Rather than espouse the usual gospel of hard, fast, loose L.A. punk, Los Angeles was dramatic and full of dark, magnificent, differing tempos, noisy ragers and creaky slow songs, all featuring off-kilter harmony vocals from Doe and Cervenka and that same pair’s craftily Beat/pulp poetic images with cunning, calm characters to guide the debut. All that, and Cervenka married Doe, on April 6, 1980, after having been tied at the hip as titans of that city’s poetry-reading scene.

“At that point, the possibilities were endless,” says Doe. “We were part of an exciting, eclectic scene that was just bearing fruit. It was becoming more challenging, that scene, due to the then-sudden inclusion of hardcore, but we were coming off a great high—several of them.”

What followed, however, within weeks and months of the release of Los Angeles—several deaths in the X family (literal and figurative) and the premiere of director Penelope Spheeris’ wrong-headed The Decline Of Western Civilization documentary—would subvert, but not deter, the good/bad feeling going into the band’s blunter, weirder, more-driving sophomore album, 1981’s Wild Gift.

“This was filled with the oddities that weren’t on the first one,” says Bonebrake, who was just on tour with Doe for the latter’s new solo album, The Westerner.

“Wild Gift was definitely the more up-tempo album,” says Doe.

Tipped with several songs written at the same time as those that packed Los Angeles, Wild Gift, like X’s debut, was full-bloodedly produced by Manzarek, the one-time Doors keyboardist left in the lurch by Jim Morrison’s sudden death in 1971. During this, his third decade in music, Manzarek experienced a grand second act as a laissez-faire philosopher type behind the boards for four X albums (Los Angeles, Wild Gift, 1982’s Under The Big Black Sun and 1983’s More Fun In The New World).

“I had a great time with X, the greatest punk band America has ever produced,” Manzarek, who died in 2013, once said. “The power of Billy Zoom on that guitar. Don Bonebrake cracking that deep, fat marching-band snare drum. John and Exene with their Chinese harmonies were just fantastic. Real American, Los Angeles poetry. I immediately thought of Raymond Chandler, Nathanael West, that ’30s gangster stuff. Jim is part of that tradition, too.”

One step beyond the spooky, stark Los Angeles and less murkily mournful than follow-up Under The Big Black Sky, Wild Gift was more punk rock than either effort, with shorter, sharper songs, a Bukowski-like sense of humor (without all the fucking and booze) and Zoom’s rockabilly howling guitar set to stun. There were other twists. Wild Gift was slightly kitschy (for an X album) affair with twinges of surf-rock cool, which sounded a bit quaint when executed by rip-snorting Zoom and Co. It was almost pop (newly written songs such as “White Girl” and “Beyond And Back” had hooks galore), and, for the first time, its music was nicotine-scented with the ground-up, dusty twang of roots rock and country.

“That is very much who we eventually became, and it started there,” says Doe. “In 1980 into ‘81, there were new bands toying with the roots thing—we were on the leading edge of that. Gun Club, Blasters. It was the beginning of that era. Plus, we had long championed the pioneers of rock ’n’ roll like Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Eddie Cochran and Little Richard. We wore those influences on our sleeves—especially with Wild Gift.”

Bonebrake goes on to say that the blunt-yet-eclectic vibe behind Wild Gift was exactly why he joined X in the first place: “Doe and Cervenka had great oddball songs.” Though he loved being in Eyes with Charlotte Caffey (eventually with the Go-Go’s), “X could do anything: a rhumba, these great complex rhythms that I was able to bring to the mix. These guys were open to anything that sounded good.”

Good and frenzied, and even fun where Wild Gift was concerned. Like the racing theme to the remake of Jean-Luc Godard lean pulp drama Breathless the band would later execute, X’s sense of romance—the love between its central songwriters and off-beat harmonists—was in full, palpitating, fast-and-furious display on Wild Gift, a sound never to be heard again in the X catalog.

“I think Wild Gift had some of our best material,” says Zoom, before focusing on the mess that was the recording process. “It’s too bad we couldn’t do that material justice.”

So April 1980, and the release of Los Angeles …

“We were on this high, and then, two people who were really close to us died suddenly,” says Doe. He’s remarking on Cervenka’s older sister from New York City, Mirielle, a jewelry designer who came to L.A. for an X record-release party at the Whisky A Go Go only to be sideswiped by a drunk driver who ran a red light; she was killed instantly. The other “scene” family member who died was Darby Crash, the messed-up Germs co-founder who committed suicide with an intentional heroin overdose on Dec. 8, 1980. “John Lennon died that day, too,” says Cervenka quietly and matter-of-factly. “It was a very weird moment. My sister died on the way to our release party, so perhaps if we had never made that album, my sister would still be alive—so many mixed emotions.”

Bonebrake details the poignant Whisky A Go Go live party as one that should never have occurred. “We had that whole show-must-go-on mentality, but we were young—we didn’t know better,” says the drummer. “It was so tragic. Exene and John found out right before we went on. We didn’t tell anyone in the crowd. We were frustrated and freaked out. John was breaking windows. You can’t imagine.”

Cervenka talks about the yin and yang of having the greatest moment of their collective lives to that point being intertwined with the worst moments of their collective lives to that point with a sort of lofty existentialism: “With Darby dead, too, it was the end of punk, or it was as if the end had started then.”

Coming into the follow-up to Los Angeles meant a higher profile and a slightly bigger budget. There was no sense of trajectory or programming or order on the part of the band. “We had no idea, so I give Ray a lot of credit for choosing the songs and what went where,” says Doe. “We knew that ‘Johnny Hit And Run Pauline,’ ‘Soul Kitchen’ and ‘Your Phone’s Off The Hook, But You’re Not’ would be on the first album because they were crowd favorites. Other than that, it was all Ray.” In Doe’s mind, Manzarek was the trusted friend and new band mentor who understood what went where and how to progress X’s sound incrementally. “He made Wild Gift harder, faster and a little more punk rock,” says Doe. “Our conversations with Ray were never over-intellectualized. He was more about doing it than contemplating it. No master plan.” Whether it was writing lyrics or playing, everything about X was more instinctual than intellectual when it came to Wild Gift.

If Los Angeles was the dramatic 365 degrees of X (“a primer, slow songs, fast songs so you couldn’t pigeonhole us,” says Cervenka), the second album showed off “our sense of humor,” she says. More personalized songs such as “The Once Over Twice” detailed a want for something greater, but settling “for some more scotch instead.” She continues that, as a writer, she lived for whatever was inside her head, then worked to get it all out quickly.

“The really cool lines in particular,” she says. “Just get ’em out and get ‘em down—we were writing a lot of stuff down quick as we could on Wild Gift and just kept hoping the smart, funny stuff came out faster.”

The only problem between the bitter Los Angeles and Wild Gift was how they managed to get an album that sounded as good as it does, still. “Really, I still prefer Los Angeles to the way Wild Gift sounds, but the latter has its merit,” says Doe.

Bonebrake even seems to gloss over some of the headaches—the buzzing of old studio mixers and mics—and focuses more on Manzarek’s handling of the band: “He might ask for an intro twice or another occasional take, but all-in-all, he did everything that he could to make us comfortable live—he was the best objective ears. Even when we told him before doing More Fun In The New World that we were frustrated not getting on the radio, he just did some things to boost up our sound so that it was still us.” Consider, too, that Manzarek—who got handed $10,000 by Slash to record Los Angeles and $15,000 to record Wild Gift—pretty much produced both albums for free and gave the money to the studios: Golden Sound in Hollywood for the former, Clover Recorders in Los Angeles for the latter.

“Billy Zoom’s friend had this studio for the first album, and he gave us a really good rate; we probably got like $50,000 worth of studio time,” says Bonebrake. “Not on Wild Gift.”

Zoom recalls that Manzarek was a real cheerleader, but that there wasn’t enough money on Los Angeles to actually do any kind of production. “We just tried to get the songs to go to tape and playback,” he says. “Rick Perrotta had as much to do with the sound of the first album as anyone.”

When it came to Wild Gift, Zoom notes Slash was completely out of money, “and we didn’t have Rick making the sound happen. We probably should have pulled the plug on that one until we figured out how to finance it. It’s a very uneven, thin-sounding recording. We knew better; there just weren’t any options available. No other studio would let a punk band record.” Not only does Zoom go on to say that Clover was a disappointment with tons of technical problems, but “the only way we got them to let us record was to let their janitor, who was the owner’s brother-in-law, engineer. It was his first record. They had an old API desk, but it was pretty beat, and everything hummed and buzzed.”

Doe talks about pursuing and pushing X’s signature—the off-kilter, co-joined harmonies of the lead singers—with Wild Gift, and that every player had to have a part in every song. “What was she going to do otherwise—dance?” asks Doe, considering an outtake track such as “Heater” that signaled his first solo song (it appears on a subsequent Rhino reissue where both Los Angeles and Wild Gift—each barely 30 minutes in length—appear on one album.

“The song had a nice chorus and some fun lyrics, a fantasy about guns and playing around with S&M imagery that was popular at the time,” he says. “That didn’t fit us in any way.”

For all the band’s complaints, Wild Gift wound up topping nearly every important critic’s list in America, both West and East Coast. Their shows were sell-outs wherever they went, and their name was being made swiftly. There was but one more hurdle to get around mere weeks after Wild Gift’s May 1981 release: July’s release of The Decline Of Western Civilization, a documentary filmed within Los Angeles’ punk and hardcore scene throughout 1979 and 1980 with director Penelope Spheeris at its helm. Along with featuring the antics of Darby Crash and his pal Pat Smear in the Germs, bands such as Black Flag, Circle Jerks and Fear made appearances in various stages of comic-book menace. So did an unsmiling (save for Zoom, who never loses a smile) X, which also riffed through in-the-red recorded tracks like “Beyond And Back,” “Nausea,” “Unheard Music” and “We’re Desperate.”

“That was coming out as Wild Gift was making its way, and that film just sensationalized, trivialized and emphasized all the bad things that happened and could happen with any scene,” says Doe with a sadness even 35 years after that dreary, goofy documentary’s release. “She really focuses on the darkness and nihilism of the scene at that point, which was not the overwhelming feeling and attitude of Los Angeles at that time.”

Cervenka perks up and says that Spheeris’ crew were circus people, and that the woman who went on to direct Wayne’s World and the remake of The Beverly Hillbillies probably just saw L.A.’s punks as the same kind of weirdos she’d been used to her whole life. “We were probably dark carny people to her, but to us, we were just young kids who wanted to play loud and change the world at the same time,” she says.

Bonebrake, ever the gentleman, mentions how at a time when they were meant to concentrate on the woolliness of Wild Gift, The Decline Of Western Civilization was this juvenile dope/prank shitshow that made X and the scene look like what they weren’t: mindless and nihilistic. “It was a pretty narrow view where we became caricatures,” says the drummer, humorously, but building up steam. “She was filming us after a gig that ended at 2 a.m. and wanted to come to our house while we got tattoos? I went home. I didn’t want another tattoo. Plus, she added that slam-dance footage to our scenes, the sort where the audience spit at the musicians. You know how many fights we got into if someone spit at Exene? Billy Zoom wouldn’t play a show if people came up and touched his instruments, let alone mosh near him. What a weird time.”