Here’s an exclusive excerpt of the current MAGNET cover story.

Interview by Tim Blake Nelson

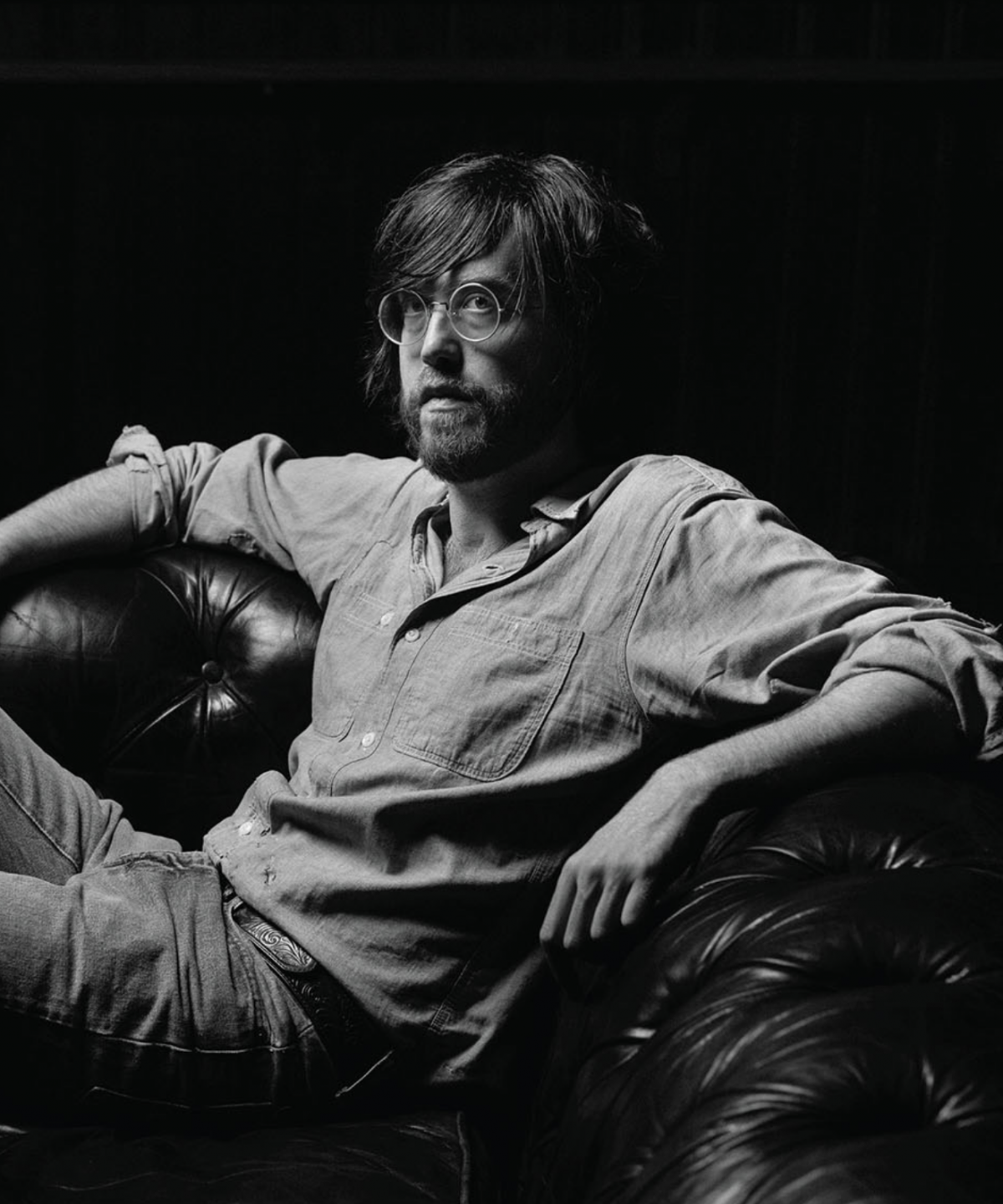

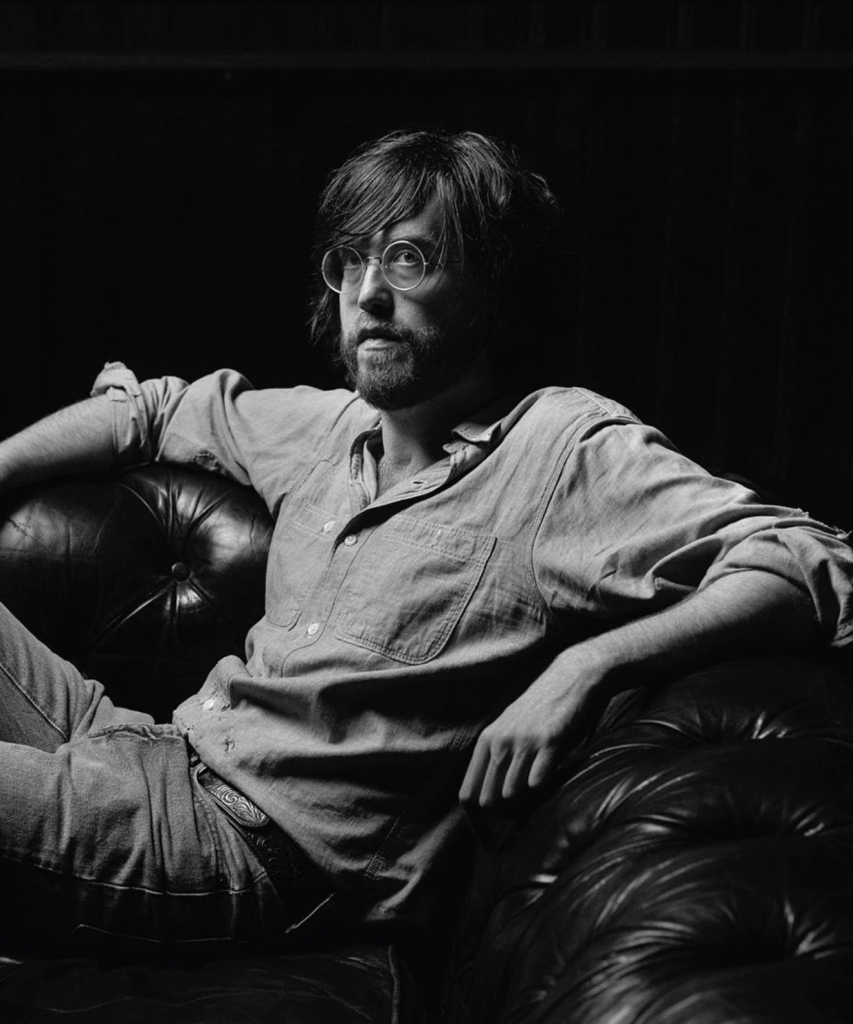

Photo by Gene Smirnov

Weird emails come our way, and all we can hope for is that they be salutary.

One that’s not: “Mr. Nelson, I’ve been knocking repeatedly on your door. I’m in the apartment just below yours, and you’re leaking on us. Our ceiling, which was hand-painted by Mark Rothko, has been ruined by water damage. Our lawyer will be in touch.” Luckily, this one hasn’t come in yet, though our pipes do leak, and one never knows what adorns the ceilings of New York dwellings.

A few months ago, however, this email did, which I would call salutary: “Tim, you might remember me from the Low Anthem concert out in Brooklyn. I represent a band called Okkervil River, and they’d love for you to appear in their new music video. Would you be interested?”

My oldest son Henry and I have been listening to Okkervil River since Henry was in the eighth grade and their breakthrough album, Black Sheep Boy, came out. Henry insists that the album “got me through eighth grade.”

We love their lyrics, and we love their sound, which frontman Will Sheff has been developing since before his days at Macalester College. Of course I was going to appear in his video—Will is actually an accomplished (if burgeoning) young director, and he’d be directing. There was also a script and a concept that made sense in all the appropriately oblique ways, meaning the video would have a measure of subjectivity and mystery and wouldn’t just be some overly literal narrative redundant to the song’s lyrics.

I ventured upstate a ways to Ulster County, N.Y., and on the first of the two days allocated for the shoot, Will asked if Henry, who’s now 17 and hopes one day to do what Will does, would like to come up and be in the video playing guitar. It ended up being one of the best days of our summer.

As a sort of lagniappe, MAGNET asked if I’d interview Will in anticipation of the release of Okkervil River’s new album, Away. Will is a fascinating, wise and generous soul. It’s been a pleasure getting to know him, and I hope you’ll enjoy this interview.

—Tim Blake Nelson

Sheff: What’s going on, man? Where are you right now?

Nelson: I’m in New York, but I’m in the middle of shooting a film in Utah called Deidra & Laney Rob A Train. I’m headed out to finish that this week. Where are you?

Sheff: I’m in New York, too. I had a lot of work that just happened. We just played some shows. We went up to New England to play some little shows where we played the record in order for the first time, and that culminated with a show we did here with a live orchestra. And now I’m actually done with work for a little while, for three or four weeks.

Nelson: Can I ask you a question about playing the record in order? How do you decide the song order on a record?

Sheff: I used to have actual formulas. Brian Beattie, the producer who I worked with when I first started making records, he was a mentor to me in a lot of ways. A lot that have to do with music and a lot that have to do with life. He was really influential for me. He had a little formula. A lot of people put the most accessible songs first, but he always used to say, “The first three songs are the accessible ones, and they are for the audience, and track number four is for you.” It’s a confession in a way to open with something that feels really accessible and then you give yourself a bone after with the fourth. You know, in the past I used to follow that formula, and I used to make sure the tempo wasn’t slacking too much, but I kind of threw out a lot of that stuff on this new record. I started it with not a clear idea. It was really just for me; it was therapy. I was trying to help myself at a time when I was confused.

Nelson: When I was growing up—I’m 52—records were records and you had an a-side and a b-side. There were two factors that went into it. A first song on the record and a last song on the record, but also a first song on the b-side and a last song on the a-side. Now, we’re in this hybrid area where you have to decide the first and last song on the CD, but probably, since you’re going to put out vinyl because of the appetite for that in indie rock, you have to order them for vinyl as well. Is that true?

Sheff: It’s kind of a funny thing, because now with streaming and Spotify and all that, they might not even listen to the whole record at all. They might jump on to one song that they heard on a “recommended for you” playlist, and that might be the only song they know. And bands have made their entire careers on that one song. As an artist myself, I want to make the best art that I can, and I can’t come up with a replacement for a set of songs in order. If you really want to go deep into something and be transported to a place, it’s better to go there in 45 minutes than three minutes and 30 seconds.

Nelson: Like a record such as Black Sheep Boy that’s around an entire theme.

Sheff: Exactly. I like doing that. It’s the best way to go really deep into a world instead of having a single serving of something.

Nelson: What’s the theme of Away?

Sheff: I would describe it as less of a theme and more of a mood. I wanted to do something more open air, something more mysterious and more organic, as opposed to trying to make something more specific. I wanted to make a whole piece.

Nelson: You said you got to the point as a songwriter where you figured out how to write songs, like a formula. You said you had come to that place and wanted to break out of it, to move away from it. Could you talk about that part of being a songwriter?

Sheff: Yeah, I think I used to be really impressed by smart songwriting. The apex of that would be Elvis Costello or something like that. Where you’re in awe of the lyrics and how everything ties in. A strong sense of an organizing brain. I wanted something different, like when you’re starting out and you don’t have a lot of success or something to claim as your own, you’re trying to stay alive. I wanted to demonstrate to the world on some level that I was good at that kind of thing, that I could write in that clever style. I felt that I got better and better at it, and then I started to realize that none of that yielded songs that I was particularly feeling. People were impressed, but I felt like I had done a parlor trick instead of made a work of art. My favorite music that really gives me reassurance and comfort and hope is not sort of smarty-pants, clever music. It’s music that I can’t really explain the wholeness. Or why it’s so beautiful or hopeful. I couldn’t even tell you what the whole song is about. I could maybe get close, but there’s kind of like an extra presence in the song that’s like magic or has an otherworldly quality to it. It doesn’t need to be smart or sophisticated; it just has this thing that’s a comfortable and beautiful quality. So I started to abandon what I thought about what I had figured out about writing songs and started to try to do the other thing. To open it up for the wind in the trees, if that makes sense.

Nelson: That’s interesting. So, Will, you directed a short film and this last music video in which my son and I were very lucky to appear. And you draw and make T-shirts, even. Can you talk to me about the synergy of the creative process, and for you personally, how songwriting opens up other creative avenues such as drawing or directing? How does that make you a better songwriter?

Sheff: I think the short answer for making a better songwriter is I’m fascinated by the rules that make artwork good. I guess not “good”; I don’t know if I believe in objective “good,” but what makes art communicate with people. Some of those rules are the same across other mediums, but some of them aren’t. I’m really fascinated with cracking that nut. Figuring out what about music is applicable to film and what’s not. When I was a kid, I was in the hospital a lot and I couldn’t see very well, and those things contributed to me being in a bubble. And creativity kept me company. I was a kid, so I hadn’t really thought about if I wanted to be an actor or a musician or a filmmaker, but it was just a fun, warm cloud of creativity keeping me company. As I get older, it becomes more clear to me that this is something really deep that motivates me, to keep communicating with that childlike quality. I don’t want to lose contact with that cloud of imagination. One of those ways to do that is always having a way to be creative. You seem that way, too. When you weren’t acting, you were writing or taking pictures. In a way, it’s natural. Do you feel it’s true for you, too?

Nelson: I get as much joy out of acting as I do writing and directing movies, and I certainly enjoy photography as well and keep a journal. My oldest son, Henry—who was in your video—we share a need to create something every day. The day isn’t complete until there is a tangible creative output, even if it’s something that people won’t see. In terms of acting, I’m dependent on others to do my work. So I started to write my own scripts so I didn’t need to depend on others to be creative.

Sheff: I can really relate to that. When I first started out, leaving high school, everybody would say, “Oh, he wants to be a director.” That was my passion. I would make movies with my friends. I would then realize your friends sometimes bail on you. [Laughs] Then I went to college and learned there was so much money involved, but music could just be me and my guitar, and me recording what I wrote. It was this really, really simple way to make art. I really love collaboration, but I always feel that I need space to come back to me just being me. When I wrote this record, I wasn’t thinking about the band. I wasn’t writing for anything to be released; it just came back to me. The muse, the gods of art or whatever—that sounds pretentious—but I felt like there was an invisible person around watching me, who I was trying to make happy. Sometimes, I think that’s what this record is, between me and everything I love to do.

Nelson: Like an amalgam of all of your influences.

Sheff: I guess so. The amount of delight I got from Marx Brothers movies or William Faulkner, it felt like a father and mother to me. During times when I felt very alone, I had these things to be my whole universe or my friend group—that stuff all gets added to a big, sticky ball of love and influence, and I wanted to keep in communication with that.

Nelson: Yeah, I wanted to say, as a parent, I got one kid who wants to be an actor and one who wants to be a musician, like you, and one who’s tremendous with math and history, and maybe he’ll be a lawyer or invent video games, but it’s amazing every time we go to a museum and stand in front of a Miro or a Picasso. I ask them as I ask myself, “How can this affect my creativity going forward?” It could be a cubist Picasso painting, and I’ll ask my son, “How can this influence how you write a song?” Or my son who loves math, Eli, “Is there a way that you can approach a math problem on a different plane the way that Picasso approached this painting? Is this applicable to the way you play a role?” In any creative enterprise, you have to draw from other media, especially in this day and age where technology gives us access in any given moment to any influence that we wish to receive.

Sheff: Yeah, there’s people who talk about if you go ahead and try to steal someone’s idea, it’s not a bad thing to do because unless you have a knack for mimicry, you’re going to do it wrong. Getting it wrong means making something original. I was into Irish music in high school, so I would hear all these different versions of songs, and I would hear how someone would add a verse or remove a verse, and then I got into old-time music and realized how far back that goes. Then I would hear a Dylan song and realize, “That’s a Carter Family song.” I realized there was this whole universe of people talking to each other through time. It’s a deep heart of what creativity is. I’ve always felt there’s something wonderful about taking a piece and using it as a jumping-off point into another piece. That’s definitely something I try really hard to do, like trying to revamp an old Washington Phillips gospel song. There’s another one that takes an old Western cowboy form as well. It takes lessons from those stories and puts them in a modern songwriting context.