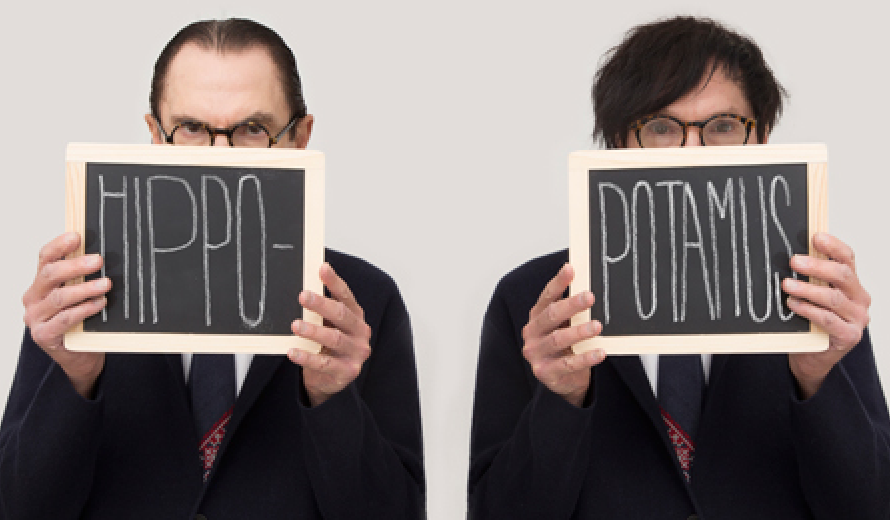

The hammering glam pop of 1974’s Kimono My House, the lush arpeggiating disco of 1979’s No. 1 In Heaven, the spiky new wave of 1982’s Angst In My Pants, the edgy synth-house of 1994’s Gratuitous Sax & Senseless Violins, the wily art-baroque of its newest album, Hippopotamus (BMG): Only the sonic wallpaper changes when it comes to the Mael brothers of Sparks. Russell sings their songs in a high, quavering voice, while Ron plays and writes them in gorgeously complex fashion. Along with Hippopotamus, the Maels are involved with the long-awaited Annette, their filmic, musical script about a stand-up comedian whose opera singer wife dies and he finds himself alone with a two-year-old daughter with a surprising gift. Sounds like a Sparks song to me.

It’s 46 years since your debut as Halfnelson. When did you think to yourselves, “No, Sparks is better”?

Russell: That moment arrived as a result of Albert Grossman, the owner of Bearsville Records. He loved our first album but was disappointed that it didn’t sell as much as he’d hoped—that it deserved to sell more. He thought the name Halfnelson was holding it back, that it was so obscure as to cause a problem. We didn’t see that, but we didn’t own the label. He said that we were humorous people, that we reminded him of the Marx Brothers, and why didn’t we call ourselves the Sparks Brothers, but we didn’t like that idea.

Ron: We said, “Perhaps we’ll meet you halfway,” and that’s where Sparks came in.

How has the art of Sparks most changed since your start, beyond stylistic changes?

Ron: I think there’s still this certain sensibility running through everything we do, despite all the stylistic changes and external trappings. Whether we’re working with a band, orchestras or just each other, we have faith in three- , four-minute songs. We believe there are still roads we haven’t taken. I think that we can do an album like Hippopotamus now that still surprises people. That’s what we seek to do. It’s not as if we’ve changed. It’s the fact that we’ve continued and are able to do this that’s amazing.

Seeing as your songs seem so ordered, despite the chaos within, are the two of you almost always of the same mind? And if not, where do you two differ, and how are these differences resolved?

Russell: Generally, we’re of the same mind; you’re right. When we’re not, they’re about lesser issues. Nothing grand. If so, we get on a similar path and go for it.

Ron: Amen.

Smaller squabbles. Like what?

Ron: Marital issues. Song choices for an album. Sounds. Nothing much. It’s not as if we’re frustrated by having the same POV or that we could be doing something outside of Sparks.

Ron has almost always written all the lyrics.

Russell: With the exception of the classics “Pineapple” and “Gone With The Wind.” Mine only ever come around every 10 years.

Ron: They’re generational.

Yes, but why did that come to pass? Why does Ron seek to complicate your life as a singer with tongue twisters like “Life With The Macbeths” or “Scandinavian Design” on the new album?

Ron: I don’t want to be limited by the thought of how a singer might sing my songs. That’s not my problem.

Russell: Yes, they’re challenging, but in retrospect, I think I’ve distanced myself in that I look at what else is going on in pop music and find it better to have such complexity. That makes those songs more special. They stick out from the crowd. That and having a key that goes all over the map is why Sparks sound like we sound. I embrace it.

On the song “Hippopotamus,” there’s a Volkswagen microbus, Titus Andronicus and a woman with an abacus. That’s such a silly rhyme scheme. I don’t have a question. I just wanted to repeat those lyrics to you because I’m trying to picture that session.

Russell: It’s not as much fun as you’re picturing.

Last time we spoke for MAGNET, I asked about this movie musical you were working on. You couldn’t say much then, but now … you’re laughing.

Ron: I’m laughing because we can’t tell you much more now.

Russell: It’s called Annette now, and we’re collaborating with Leos Carax, who last did Holy Motors.

How did the relationship start with Carax? You must like him a lot because he’s the topic of your new tune “When You’re A French Director.”

Russell: He used our song “How Are You Getting Home?” on Holy Motors, and as a result of that, we met him in Cannes after just finishing what would’ve been our next record, this highly narrative album, Annette. He asked to hear it and loved it so much. He said he wanted to direct it as his next film, so Annette suddenly took a different course—it no longer became Sparks’ next album. We recorded Hippopotamus for release in its stead, and now, we’re far along in preproduction having written a script and cast Adam Driver and Michelle Williams. It’s shaping up nicely.

So Williams, and not Rihanna, who was rumored at first? Are you enjoying the longer-than-a-pop-song process?

Russell: Oh yes, the dialogue, the acting, everything. The more Leos gets involved, he wants certain rewrites, so we’re in that process.

Ron: Then again, we’ve been in that process for the last 45 years. It’s a great challenge for us to work in such a long narrative way because we’re used to four-minute songs, where the starts and ends are so contained. A script like this shifts your way of thinking, to have to make something that needs to continue to make sense over a two-hour period.

Russell: We’re just delighted that it’s finally going to start filming at the beginning of next year.

Ron: When your lead actor is the evilest villain of all time in the Star Wars universe, some things just take time.

—A.D. Amorosi