“Simply put, rock rarely gets this good.”

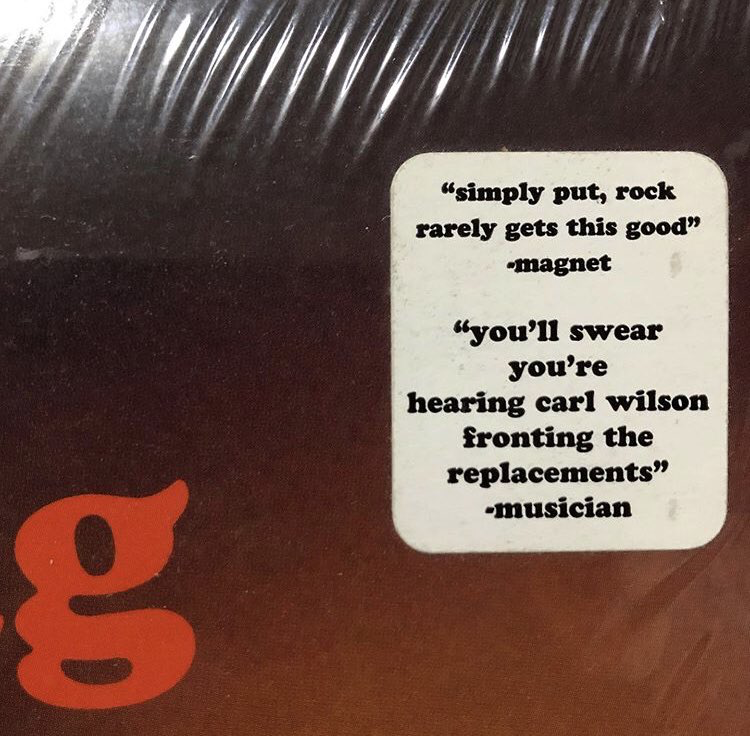

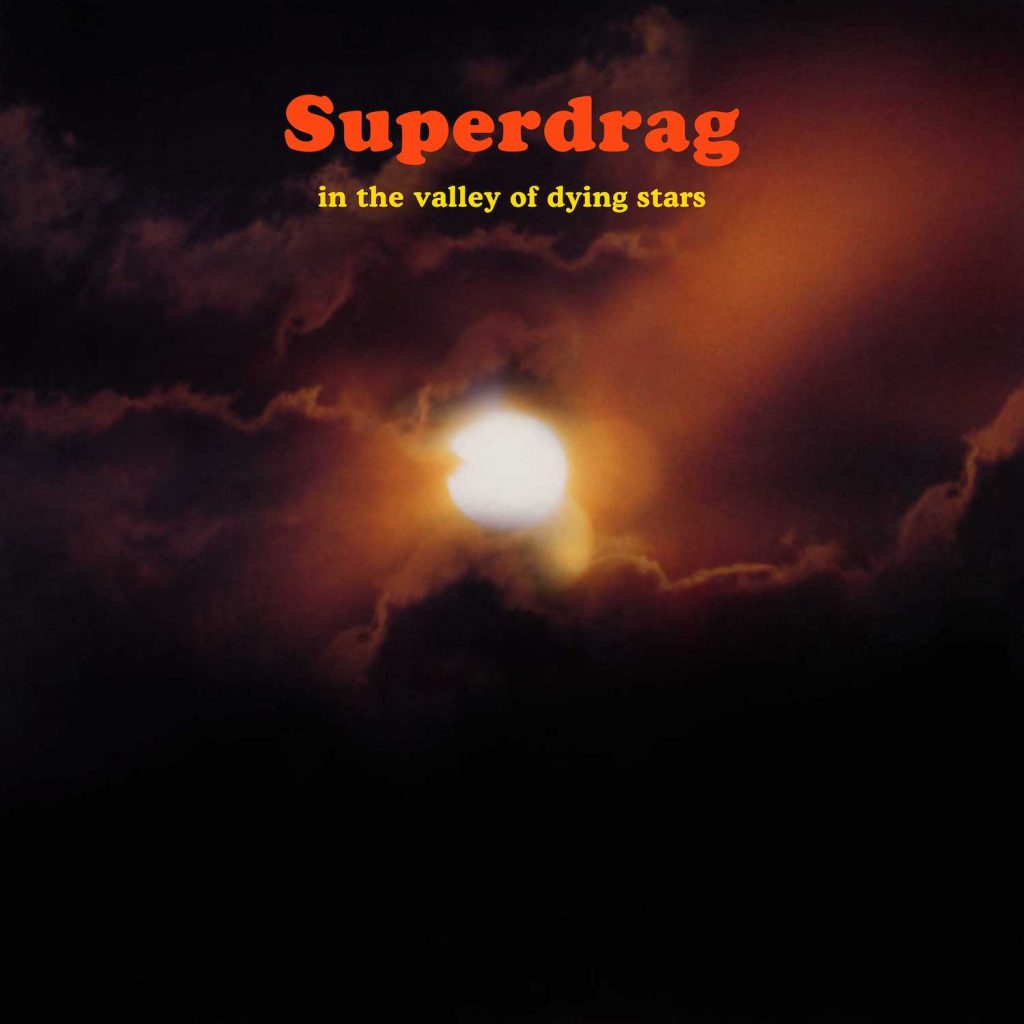

Those words—so sharp and pithy they made the record’s hype sticker—were part of MAGNET’s review (by yours truly) of In The Valley Of Dying Stars, the third full-length from Knoxville, Tenn.-based power-pop quartet Superdrag, released Oct. 17, 2000.

Simply put, they undersold things.

Led by singer/songwriter John Davis—underappreciated then and now as one of the finest tunesmiths of his generation—Superdrag was already on a winning streak, having produced 1996’s major-label debut Regretfully Yours followed by 1998’s psych-tinged Head Trip In Every Key. In The Valley Of Dying Stars remarkably topped them both. A moving meditation on life, love and, especially, loss, the record deeply resonated with fans—despite the moronic indifference of Elektra, the label originally slated to release it. Two decades later, In The Valley has lost none of its emotional power and vitality, and is the effort many, if not most, Superdrag fans cite as the band’s pinnacle.

To commemorate its 20th anniversary, Davis and Co. put together a limited-edition vinyl repress—1,000 copies in transparent orange, Coke-bottle clear and black variants housed in a gatefold sleeve and featuring an eight-page booklet with never-before-seen photos and other ephemera—along with a T-shirt that can be purchased separately or in a bundle. Pre-orders are available now, with product shipping in early 2021. (NOTE: Due to the response to the pre-order, 150 black copies have been added to the store, as well as 200 in transparent red.)

This is the story of In The Valley Of Dying Stars‘ creation in the wake of record-company bullshit, band upheaval, death and more record-company bullshit, as told by the principles. You’ll find they rightfully think it’s a classic, too.

—Matt Hickey

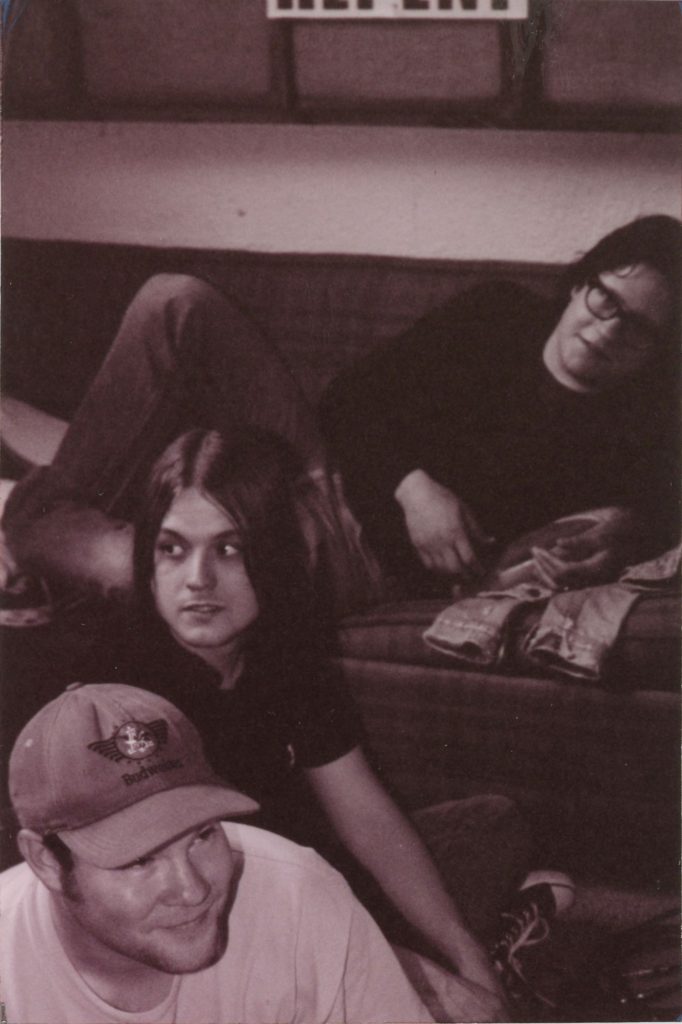

Who’s who:

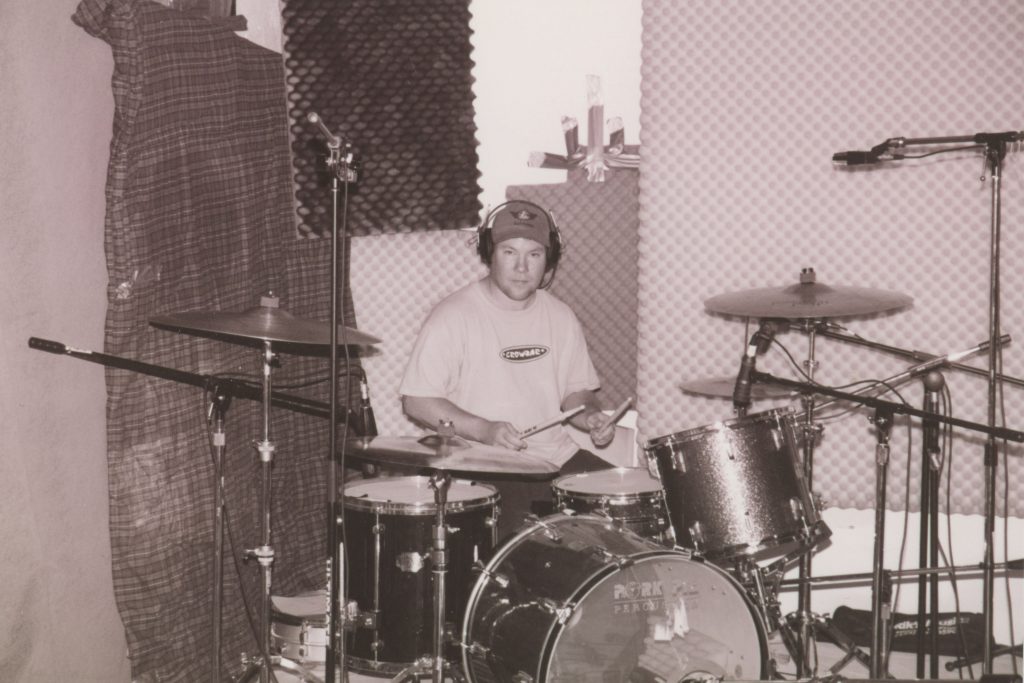

Don Coffey Jr. (drummer)

Jim Cortez (radio promotion, Elektra Records)

John Davis (singer/songwriter/guitarist/pianist/organist, etc.)

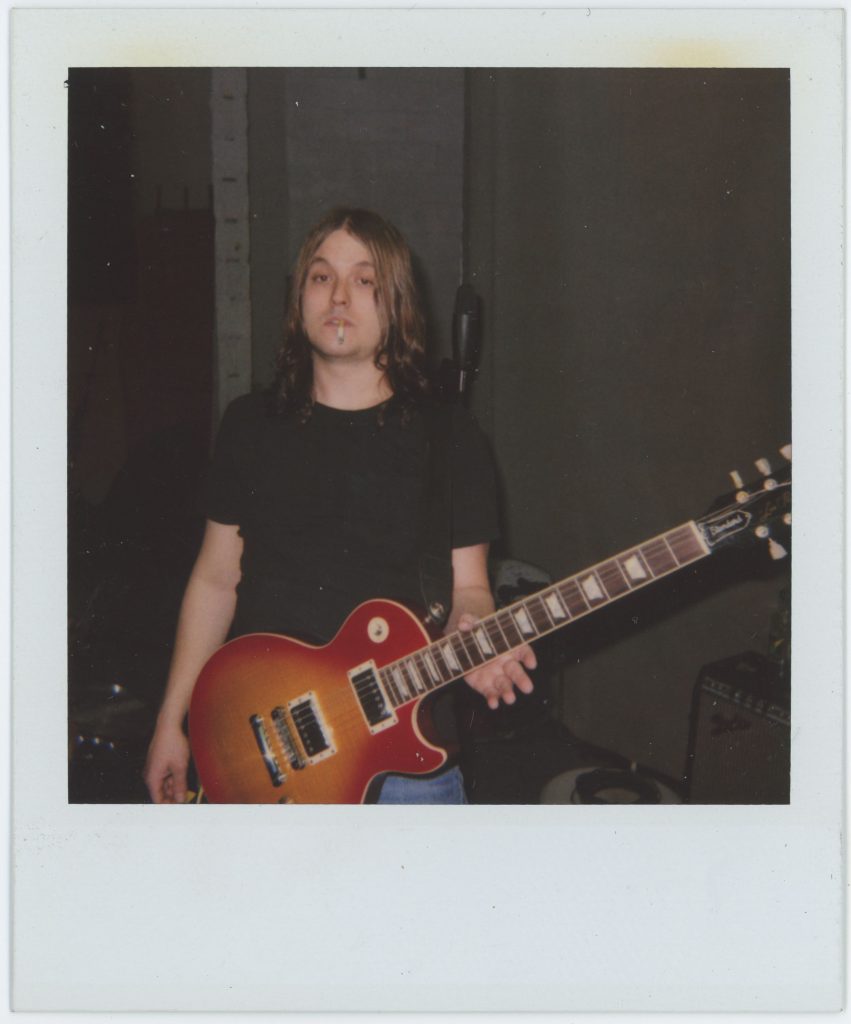

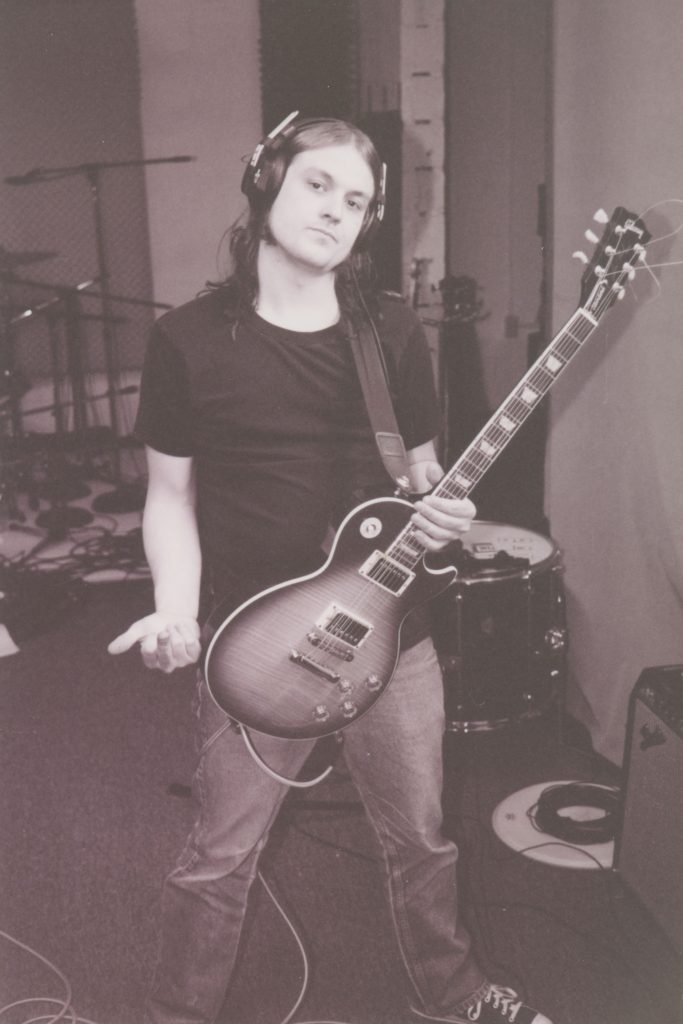

Brandon Fisher (guitarist, 1993-2000, 2007-2010)

Greg Glover (owner, Arena Rock Recording Company)

Jake Ottmann (manager, 1994-2000)

Tom Pappas (bassist, 1993-1999, 2007-2010)

Sam Powers (bassist/vocalist, 1999-2003)

Nick Raskulinecz (producer/mixer, “fifth member” since 1994)

Jamie “Stealth” Shoemaker (front-of-house engineer, 1995-1999, 2007-2010)

Steve Wennerberg (tour manager, 1996-1998)

Coffey: It’s hard for me to start talking about Valley without mentioning what came before. In a general sense, what I will term “record-label meddling” started with “Sucked Out” (from Regretfully Yours). Elektra kind of left us alone on Head Trip until the end, when it became apparent they didn’t like it and they didn’t know how to work it to radio. “Do The Vampire” comes to mind.

Davis: There was one person at Elektra that cared the most about Superdrag and Head Trip In Every Key. His name is Jim Cortez. His efforts on our behalf will never be forgotten.

Cortez: I fucking screamed at them all, on conference calls, in boardrooms, at lunches and dinners, saying they were fucked for not putting everything into Head Trip. Many, if not all, the other promo people hated me for it. To them, it was just another record to work. Fuck that! Wow, man, I still get riled up! We did a lot of promotion in the Northeast and I got “Vampire” played. The song did fine and the gigs were solid, but I couldn’t get any love from my own peers at the company.

Coffey: I enjoy the process of recording. Not everyone does. In other words, I don’t just get my bit done and take off. (Head Trip producer) Jerry Finn was pretty hard on me, but I wanted it to be good and I can take constructive criticism, like, “Hmmm, no … do it again.” Fear is also a motivating factor. I was scared to death Jerry was gonna bring in somebody else. I distinctly remember Tom (Pappas) saying, “This ain’t the way the Stooges did shit, man!” I could tell he was frustrated, but I didn’t know what to do about it. I just didn’t know how to help, other than to be there for moral support while he cut his tracks. I’m sure I went to get a beer or a bite, but after the drums were done, I was in the control room trying to absorb everything Jerry and Nick (Raskulinecz) did. Not to go too far back, but Head Trip was supposed to be made at Ardent. While we were there trying to get drum sounds, my grandfather died. This became a valuable experience for me on Valley. It seems like I got back from the funeral and within days, we were moving operations to Sound City. I had to tell Jody Stephens. That flat-out sucked. It was my introduction to playing the role of middleman.

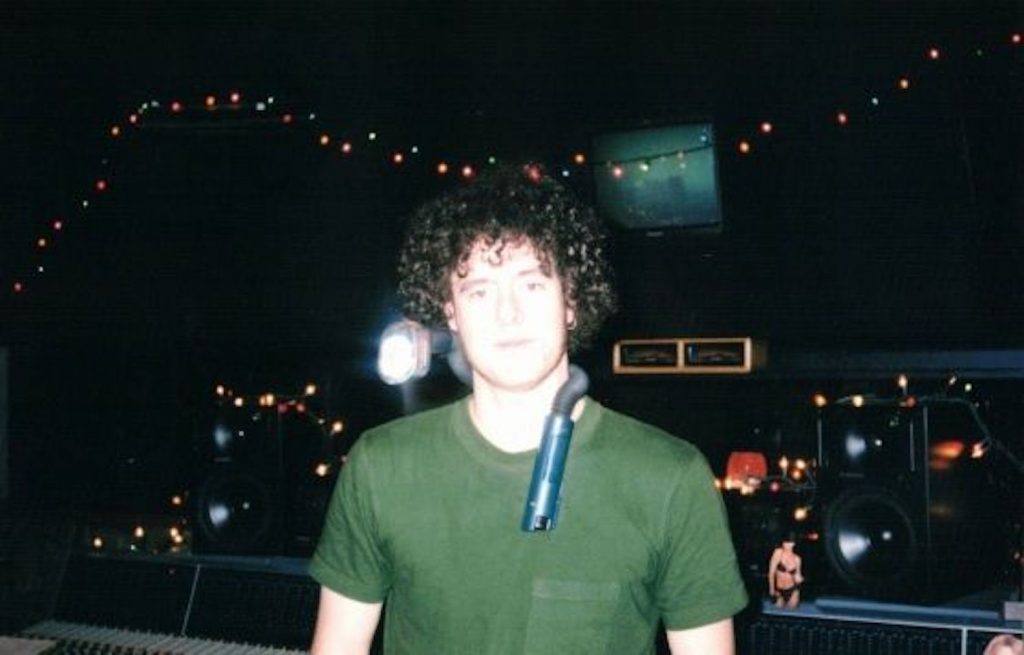

Davis: In my mind, the story of In The Valley Of Dying Stars begins at Stealth Studio in Knoxville. It was named after our front-of-house engineer, Jamie “Stealth” Shoemaker, who happens to be a comedic genius. He got that nickname from our tour manager, Steve Wennerberg, because he used to weigh in on conversations happening outside the curtain while zipped up in his bunk and invisible. Steve has a way with words. He gave everybody nicknames.

Wennerberg: John Davis. “The Chickasaw.” This guy is some kind of documented American Indian who wants to be John Lennon? What is this bullshit? John could make you laugh. He could speak on almost any subject and find a funny way to spin it. He was so thrilled with the duty-free shop at Heathrow after the band’s first trip to England that we were calling him “Duty-Free” and made the whole thing a ritual at border crossings and such. Brandon Fisher, a.k.a. “Garnish.” The nerve of this guy. Every night, he’d walk out onstage and refuse to play guitar. Instead, he would generate this subversive padding, delivering a sonic backdrop, which, if you could visualize it, looked a lot like what this guy ate for dinner every night. In a word, “Garnish.” Tom Pappas, a.k.a. “The Plant.” Whether he was speaking like a machine, speaking in tongues or spewing out what sounded like Yiddish at a couple thousand miles an hour, “The Plant” was pretty much always fully engaged. He had a can-do spirit. I merely suggested to him once in conversation that he might as well headbutt me. He did. It was a good shot. It hurt. Didn’t seem to hurt him at all. Donald Ray Coffey Jr., a.k.a. “Café Ray,” the fireplug, the pitbull. If he sunk his teeth in, he was not letting go. With Don, it was all about Superdrag. He beat the tar out of his drums. He beat the shit out of himself in a lot of ways. Given his druthers, he would have Superdrag onstage every night of the year. He once played with a broken hand for a couple of weeks.

Cortez: I was in the biz for a long time, and as long as I didn’t have to wear a suit and got free records, I didn’t care about anything else but the music. I worked with a lot of big and not-so-big bands, but I have to say that out of all of them, it was the Georgia Satellites and Superdrag I loved the most, musically and personally. It felt like family every time I got to see them. Johnny is like my little brother from another mother. We have the same musical DNA for sure. He’s a genius. Flat out. I know he doesn’t like to hear it, but fuck you, Johnny Boy, you’re a genius. And your perfect humility is what makes you beautiful. Brandon is an angel of a guy whose wings are his fingers on that guitar. Don is one of the best drummers I’ve ever seen. Or felt. And Tom—onstage, Tom was the soul of the band.

Shoemaker: I remember wrapping up the touring for Head Trip before we started work on the demos for Valley. We were all pretty burnt. My memory says that tour was pretty miserable for all of us, so we weren’t in the most positive states of mind. Elektra didn’t do much of anything to promote the record, and it was mostly downhill from there.

Cortez: I fought for “Hellbent” to be the next single and won, hoping it would keep Head Trip alive and keep the band on the road. You know that sinking feeling you have when “all your love’s in vain”? Yeah. I was feeling that way. I got some stations to play “Hellbent,” and the band did some radio festivals to back it up. Those were amazing shows. So much fun.

Ottmann: I felt like I was on the comedown from some sort of meth bender, the result of “Sucked Out,” which, as a young, first-time band manager, was the adventure of a lifetime. Managing Superdrag with my business partner, Scott Cymbala, during that time is a novel all by itself. It was one of the best periods of my life. We went from being nobodies to a bunch of somebodies real fucking fast. We reached the top of the mountain. But with all things that go up that fast, coming down the other side is always a precipitous fall. By the end of album two, the band and I were without a label, and without all the stuff that comes with a hit. I was bitter and disappointed we weren’t playing Madison Square Garden. I remember the time immediately leading up to the making of In The Valley Of Dying Stars as being a crossroads for me. I had recently started a relationship with a woman I just knew I was going to marry, have kids with and start a life with. She would come over to my loft in a semi-abandoned warehouse district in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, one that was set up almost exclusively as a layover for bands, tour buses and crew, and, seeing the bodies of stinky dudes on the floor, likely thinking, “Well, this isn’t going to work.”

Pappas: We spent a longer time recording Head Trip than we did supporting it. Nonetheless, it’s a great record.

Davis: The campaign of touring behind Head Trip In Every Key had already gone out not with a bang but with a whimper. For the most part, anyway. We needed a steady base of operations where we could store all the gear, write, rehearse and make demos for a third album.

Fisher: Moving into Stealth Studio was such a critical part of the In The Valley Of Dying Stars era. It was perfect for us. We could rehearse, record and just hang out any time we wanted.

Davis: I guess you could say the studio name had a double meaning, because the building looked totally nondescript from the outside. Don’t go looking for it, by the way, it’s not there anymore. TDOT took it out years ago for a new interchange.

Shoemaker: I’d badgered the guys and Don in particular on that tour to start investing in some recording gear so they could have some control and not bleed money when they wanted to demo stuff. I can’t remember how we got all of the gear, but I think Don and Superdrag bought some of it, and I supplied my limited mics, cables and outboard gear. It was all set up in a pretty sweet practice space they’d recently acquired.

Davis: Don led the charge on finding the spot and making it into a viable workspace. I feel like he and Tom worked together on soundproofing it. Don also built a rack for all the guitars. The recording rig was pretty spartan to begin with.

Shoemaker: I don’t think we had more than five mics, maybe one condenser, no external mic pres, an eight-track reel-to-reel, a crappy Alesis compressor, a DAT recorder and a Yamaha effects unit. Other than the DAT, no digital capabilities or automation.

Davis: With touring operations suspended, the focus was on generating new material. Brandon and I spent a lot of time experimenting with “The Warmth Of A Tomb,” the first song written for the LP. The time signature and the vibe changed a couple of times before the band arranged it. To my ears, the finished version is a classic example of Brandon’s guitar style: producing complementary moods through the use of arpeggios, drones and different textures. In this case, everything is very mellow, but that could also mean total chaos.

Fisher: We spent a fair amount of time arranging the guitars on “The Warmth Of A Tomb.” The chorus started out in 3/4, and we’d play through those changes, along with the turnaround, over and over. I think we might’ve recorded just the chorus and turnaround guitar parts on the four-track in John’s apartment before he finished the song. I’d recently gotten an EBow, and it made an appearance during the outro.

Davis: To my recollection, the vibe between us and the record company started getting a lot weirder during the eight-track Stealth phase. I was used to feeling some internal pressure to keep the songs coming, but I definitely started feeling a lot more pressure from outside forces then. For the first time since the band started, I’d run out of ideas for longer periods at a time than ever before, largely due to those pressures, I think. But I still had to have “ideas” even when there weren’t any ideas.

Shoemaker: My fondest memory of the eight-track sessions is probably taking a trip over to John’s apartment to record his upright piano for (non-LP track) “Doctors Are Dead,” a great tune. (Another non-LP track) “I Find You” is one of my favorite Superdrag tunes.

Davis: We knew that after Head Trip stalled, we were in a position of having to justify our existence at Elektra. Luckily, they had already picked up their option on our third LP, which ended up serving us very well a few months later.

Coffey: I think when we got to Woodland Studios in Nashville the first time, it was really a demo session for Nick. Looking back on it, how stupid is that? Damn stupid. John and Nick worked really well together, and the label wanted to test Nick’s chops? “Whaaaaaaaat?” When we wanted him to accompany us to Bearsville for Head Trip, they didn’t blink, so why now? He was even more experienced by the time we went to Woodland. Something was up.

Raskulinecz: John called me. He told me the label was ready for the follow-up to Head Trip. We talked about how great it would be if this time he didn’t have to bring in any outside producers or writers or anybody outside of the five of us. I agreed. I had been working at Sound City for almost five years at this point. I really felt confident I could produce the record with the experience I’d gained. I knew what the fuck I was doing, and I was ready for anything. I spoke with Josh (Deutsch), the band’s A&R at Elektra. I could tell pretty much right away there was no interest in me producing the record. It was more like, “Let’s do what we did in Bearsville for the last record. Go make some demos, send them to us, and we’ll find a big name to produce.” That didn’t matter to me, I had nothing to lose, so we went for it from day one.

Davis: We wanted Nick Raskulinecz to produce the next record with us. Anybody that knows anything about us knows about NR. I couldn’t tell you how we ended up at Woodland specifically. They were dealing with some tornado damage at the time, and nobody told us much about the history of the place—which is extremely rich. Slim Harpo recorded there. But they did tell us that the Neve console in the A Room used to belong to the Beach Boys. What more did we really need to know? It used to be a movie theater, and the reverb plates were up in the projection room, if memory serves.

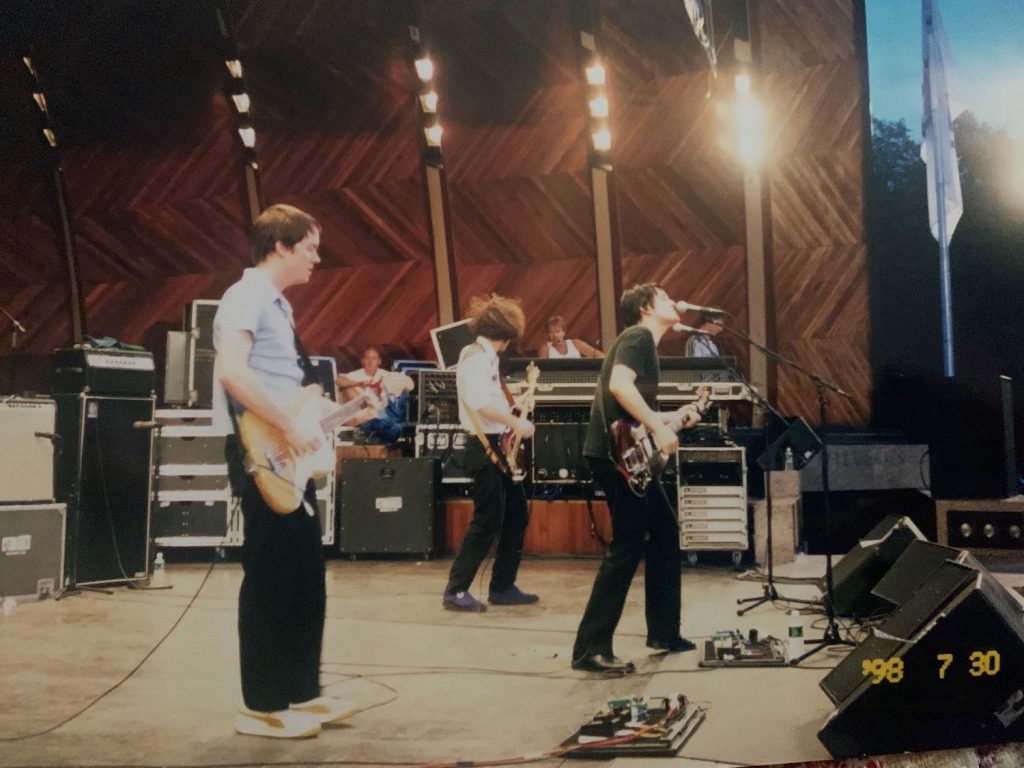

Fisher: We spent a lot of time creating full-band arrangements of the new songs, and we were well-rehearsed when we started the record. It seems like John brought in a lot of finished songs ready for the band to work up, but I also recall us just jamming on ideas, parts, etc.

Raskulinecz: We recorded two sessions at Woodland. It’s a cool, old studio in the east part of town. There were three or four studios in the building. We were in the big, main tracking room. A nice, big room for recording drums. I think we had two weeks booked at the studio.

Davis: Sadly, on day one of the session, Dec. 11, 1998, while we were loading in there and building our worlds, I got the phone call telling me that my grandpop J.T. had died. It was very sudden. I had to go home immediately. The rest of the guys stayed and did what they could without me.

Raskulinecz: John got the call that his grandfather had passed away. He was crushed—we were all crushed for him. He immediately went back to Knoxville to be with his family. I don’t remember what we did while he was gone. I doubt much. Maybe some bass or stuff with Brandon.

Pappas: J.T. was a fine human being, whom I have fond memories of. May his memory be eternal in the sight of Almighty God.

Coffey: When John’s grandpop died, it was kind of a helpless feeling, but it took me back to when my grandfather died. “What can I do?” Nick and I recorded drums for a song. It was very important, in my mind, that John have something to dive into as soon as he walked through the door. It was a way to pay my respects, and I hoped it might help him take his mind off it, if only for a brief moment. My recollection is he walked in the door and played “Ambulance Driver,” which he wrote in his head on the drive back to Nashville.

Fisher: Once John returned, I feel like tracking went really well. We were super-happy with everything and were moving at a pretty good pace.

Davis: Don performed two amazing feats at Woodland Studios that should be noted for posterity: First off, while I was in Knoxville, Don put down the drums for “The Warmth Of A Tomb” with no scratch guitar, no scratch piano and no click. He just played the arrangement from memory, by himself, and that’s what’s on the record. That’s amazing. I would estimate that 85 percent of the drum sound on that track is one mono room mic, a big RCA ribbon mic like the kind they’d use at Sun Studio to record the entire band. Months later, the other amazing feat was that he only played “Unprepared” once. The drums and piano you hear on the record went down live together in one take. We were well-rehearsed, but still. “Magical” is not a word I would toss out casually, but I remember the feeling of it while it was happening. It was magical.

Raskulinecz: I’m pretty sure (non-LP song) “Comfortably Bummed” was the first thing we recorded. We did it up. We did basic tracks for a few songs: keeper drums, scratch guitar, bass and a guide vocal. It was great. There was no way the label wasn’t gonna love this. The band would play the song all together until we felt like we got a great performance.

Fisher: Nick has always been an integral part of the band, and we were stoked to work with him on Valley.I remember everything sounding great in the room and sounding great on tape.

Pappas: I have cloudy memories of tracking together with John, Brandon and Don and later doing bass overdubs in the control room with Nick. I used Billy Mercer’s P-Bass. Thanks, Billy!

Davis: Much of what I remember about my life for a long time after this is mostly just kind of a blur of grief. My memories of Woodland are like scenes here and there, sometimes just a frame or two. But I can tell you that Don’s playing on this album is incredible. Anybody with ears can hear it.

Raskulinecz: There was a little tape editing between some of the drum takes. Simple comping. Don was so fucking solid. His timing was right on—always. I remember the guys standing around me watching me take a razor blade to the tape with anxious anticipation. I was eager to show the band all I had learned. Using the console, cutting tape, getting cool-as-fuck guitar sounds. We were totally hanging, vibing out the studio, plugging in pedals, hanging out making music. It sounded great.

Coffey: When it was just us in the studio working, it was fine, but when the label got involved, it would devolve. It became negative for everyone. It’s difficult to create when everyone is pissed off, it just is.

Raskulinecz: We finished up the songs we had started, made roughs and sent it all to the label. I think we stopped for a couple months and then continued at Woodland. The response was lukewarm to say the least. Tom was not happy and left the band around this time.

Coffey: Tom was done with this shit. It was falling apart. Shit was not going as planned. John could handle the bass parts on the record. I don’t think he wanted to pull double duty, but he could in a pinch. I was thinking three months down the road, basically, at all times.

Davis: A lot happened in between the two sessions at Woodland. Somewhere in there, Tom quit the band. For anybody that knew Tom, this wouldn’t have come as much of a shock at the time. I still don’t know anybody with more passion for playing live rock ’n’ roll music onstage. The label had no desire to keep us on the road promoting the last record, which was already considered to be a lost cause. As for myself, I know I had zero interest in going out on the road at that point.

Pappas: One day after a rehearsal and with no prior thought, I quit the band due to lack of live shows and because I wanted to work on Flesh Vehicle. It’s very sad now that I think about it.

Fisher: It wasn’t necessarily a shock, but I was bummed out about it. I’d been playing with Tom since late ’91. I joined his band the day I met him. He came into the record shop I worked at, introduced himself, we chatted about bands we liked, then he asked me to join his band—all within about 30 minutes.

Davis: Tom was always a prolific composer in his own right. Before Superdrag, there was the Used, with Tom out front. That’s what started this whole thing. The first Flesh Vehicle tape had been out for a couple of years, which Don and I played on, and I think Tom was already tracking songs for Elastic Prose at the studio with Don drumming and Matt Fuller playing bass. Two of the tracks on that CD were actually just Tom fronting Superdrag up in Bearsville from a couple years before. He was always writing and recording his own stuff. It was awkward when he left, and things got uncomfortable for a little bit. These were miserable times, as I recall. I never blamed him for quitting, and I never held it against him. I always figured if it was going to be a struggle to keep playing music, he’d rather do it under his own umbrella. That was my take on it. It was weird but totally amicable.

Pappas: I played with Superdrag till July 1999, ending with two sensational out-of-town shows with Sloan.

Raskulinecz: The label agreed to send us all back to Woodland for another couple-week session. I remember getting the whole “We really need singles” speech from Josh.

Davis: In the meantime, I had written a few more songs that ended up on the album, like “Unprepared,” “Ambulance Driver” and “Bright Pavilions.” I bought a P-Bass and took over bass-playing duties in the studio. I have two vivid memories from the second trip. One is of my Fender Champ blowing up and actual smoke coming out of it, and the other was a guitar noise overdub on “Bright Pavilions” where we hooked up every pedal we could find in the studio and we all sat on the floor out in the big room, tweaking knobs indiscriminately. The effect in the finished track always reminds me of sirens being warped by the Doppler Effect. If you put a gun to my head and forced me to choose a favorite Superdrag recording, I’d probably pick “Bright Pavilions.”

Fisher: I always loved the arrangement on that one. I definitely remember the “Everyone turn knobs on random pedals” part for the outro. We did something similar on my guitar arpeggio part during that outro section. I recall John sitting out on the tracking floor tweaking effects through the outro as I played. I assume it was a delay, the ultimate effect being that the guitar part just becomes more amorphous at the top of each bar. We’ve actually done this a lot over the years: “You play, I’ll work the effects.”

Davis: It’s gruesome and terrible, but I also remember watching the Columbine massacre unfolding on live TV in the lounge, which means the second Woodland session happened in April of 1999.

Raskulinecz: When we got back together, we started up right where we left off, but the tone was a bit darker. We did “Some Kind Of Tragedy” and “Unprepared.” There was also a song called “Doctors Are Dead” that I don’t think we ever finished. The released version is the demo.

Fisher: “Doctors Are Dead” always felt like the companion to “The Warmth Of A Tomb.” They were written around the same time, and it was another one John and I played quite a bit in his apartment. He’d play piano and I would pick out lines to arpeggiate alongside. I’ve always loved John’s vocal melody on that one.

Davis: We attempted a version of “Doctors Are Dead” at the second session because we wanted to take advantage of the grand piano. I couldn’t get a vocal I liked, so we never finished it.

Fisher: I don’t know why, really, but my memories for 1999 aren’t exactly crystal clear; the timeline becomes jumbled for me. I know we went back to Woodland without Tom for maybe a couple of weeks and then returned to Knoxville to figure out when and where we’d finish up the record.

Raskulinecz: We pretty much worked non-stop all day and night, experimenting with sounds, mics and amplifiers. We only had 23 tracks to deal with, so every overdub had to count. There were some amazing vocal performances by John. We did most of the vocals really quick, only a few takes on a U47. Then we would double everything. I remember having a lot of fun recording “Bright Pavilions” and “Gimme Animosity,” really using all the cool recording spaces at the studio. It was all Superdrag at its best. The sound I had always imagined since ’94 was appearing before my ears, and we were doing it. Just us. Too bad Elektra didn’t feel the same way.

Davis: When all was said and done, we made six of the masters for In The Valley Of Dying Stars at Woodland: “Gimme Animosity,” “Baby’s Waiting,” “The Warmth Of A Tomb,” “Bright Pavilions,” “Unprepared” and “Some Kind Of Tragedy.” The version of “Comfortably Bummed” that eventually came out on the Japanese CD release happened there. We took a stab at “Goin’ Out,” but that one took two tries to get it right. The remake from Stealth is what ended up on the record.

Fisher: The lead section and the outro on “Goin’ Out” are both good examples of how John and I played off of one another during that era, and how I was approaching the songs thinking in terms of texture. “Can I just drone this one note? With tremolo? Cool.”

Raskulinecz: We started sending rough mixes to the label. The feedback was not what we hoped for. The awesome vibe we had was slowly disappearing as we started to feel Elektra’s lack of excitement over the tunes. In retrospect, I understand why. They wanted something to compete with what was happening on the radio in ’99. College and alternative stations were disappearing. What we were doing wasn’t really for the big “mainstream” rock stations. There wasn’t a DJ or any gimmicky bullshit. At the time, I didn’t care. I knew we were making something special and that Superdrag fans were gonna love it. I still back everything we did to this day. Too bad for Elektra—the best was yet to come.

Cortez: When John sent me demos and roughs of the Valley songs, I distinctly remember nearly driving off the road. I had deep fears of how a band could top Head Trip. Just from the roughs, I could feel those songs and knew they had accomplished what I thought was an impossible feat. But I also knew it was over at Elektra. My conversations with the head suits were not good. I was devastated but also thought it was best for the band. And it was. They were rock ’n’ roll soldiers and would make it through the ice, rain and snow.

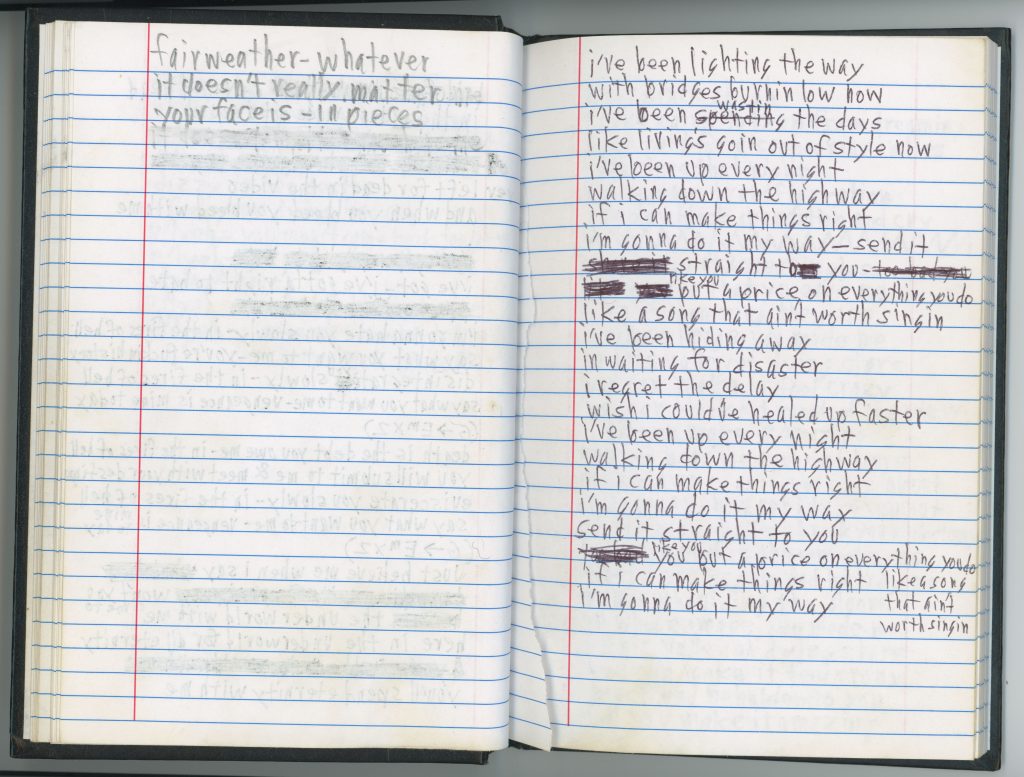

Davis: The time period just after this has been talked about the most in all the Valley press. Nothing I wrote seemed to be good enough or “emotionally direct” enough for our A&R at Elektra. There’s not much I could say that hasn’t been said a hundred times already. We were handing in songs like “Keep It Close To Me,” “Lighting The Way” and “True Believer.” He rejected all of them. This was also the time when he had me fly to New York to co-write a hit with Adam Schlesinger. My first-ever co-write with a total stranger. Bless his heart, he was kind as could be, and he made what could’ve been a really awkward situation very easy. He put me at ease immediately. I played him four-track versions of “Lighting The Way” and “True Believer,” and he said, “What am I supposed to do with these? These are finished, kick-ass songs!” So we wrote (non-LP track) “I Am Incinerator,” a.k.a. “I Guess It’s American,” instead. It was also rejected.

Raskulinecz: I went back to L.A. and waited to see what the next move was. I drove around Hollywood one night with Jerry Finn and played him what we were working on. It sounded so good. I’ll never forget the look on his face—it almost felt like we had done what he wanted to do with the band but wasn’t really “allowed” to because of the pressure from Elektra to deliver hits. He loved it. That gave me confidence in what we were doing. But I think he knew what was about to go down. We started getting word from the label that they weren’t into what was happening, and it seemed like they didn’t wanna work with the band any longer.

Coffey: The message from on high was, “We don’t hear anything.” I recall it getting to non-speaking terms. I remember telling John, “They said this,” and then telling them, “John said that.”

Davis: The last time I spoke to Josh Deutsch, we were talking about the lyrics to “Some Kind Of Tragedy.” He said, “You know what, man, nobody cares about that.” We haven’t spoken since.

Coffey: It went on for a pretty good while, until I said, “What do you want us to write?” The label said, “Make it undeniably good.” That was it. Now, how did we get out of the deal? I don’t remember who called who or much of the details. I do remember saying to the label, “Look, this isn’t gonna work out, everyone is miserable, you owe us money, let us go for X amount of money.” To which Josh replied, “You’ll never be on a major again.” They cut us a check. Done. Elektra dropped us. We can paint whatever portrait you want, but we were about halfway done with a record with no label and no bass player.

Davis: Don and Jake got us out of our deal with Elektra. I don’t know how they did it. Technically, they dropped us for “failure to deliver an album in a timely manner.”

Raskulinecz: I don’t remember a lot of communication with Elektra. It was always, “It’s no good, send more.”

Coffey: It was small potatoes for them. We didn’t negotiate a great deal. We left a lot on the table, but we were out from under it, and I had a plan. We had a very loyal group of dedicated supporters, and they didn’t really give a flying rat’s ass if you recorded on a Neve console or not.

Davis: By this time, the songs were all there. We already knew which ones we needed for the record, and we didn’t wait around for long once they cut us loose to pursue other options. We called Greg Glover at Arena Rock, and he was down to help us finish the record and put it out. Greg was a friend from way back. We met him in late ’94, I believe; he worked for Mammoth Records at the time. Imagine a Superdrag LP called Bender on Mammoth, produced and mixed by NR on cassette eight-track. It could’ve happened.

Glover: I first met the boys in Superdrag shortly after I’d moved to New York City in 1995. My first job was as an assistant at a satellite Mammoth Records office there. The label was in hot pursuit of signing them, along with several other labels. I went down to North Carolina on a Mammoth retreat, and I remember driving around listening to the band’s demos with my labelmates over and over and over. From that weekend on, Superdrag was my favorite band.

Davis: The first-ever Arena Rock record was a Superdrag seven-inch: “N.A. Kicker” backed with a cover of “Diane” by Hüsker Dü. Years later, Don, Mike Smithers and I backed up Grant Hart on a rendition of “Diane” at the Pilot Light. He stepped down off the front of the stage afterward and said, “What a treat!” That was one of the best nights of my life. But yeah, Greg was down to do the record, and it was on. To my knowledge, we never talked to anybody else.

Coffey: Greg worked for London Records at one point. He was from the South. We had some things in common. In short, we hit it off. We went by his apartment, we were pretty … well, you know. We sat on the floor in between the speakers and he played me the Meices’ Dirty Bird. I don’t recall if it was the finished deal or not, but it rocked. I trusted him from then on, for better or worse.

Ottmann: I remember a late night with the Superdrag boys after a Brooklyn show at a bar called Enid’s. Greg Glover was around then. I just was amazed at Greg and how fucking cool he was. His fucking haircut was just amazing. I still love him to this day. And damn, he still has amazing hair. G-Lover. I remember discussing with Greg, who was always a huge Superdrag fan, the idea of releasing the band’s new album on Arena Rock. Glover was now a player. He had signed Harvey Danger to his label, and they ended up having a huge breakout song, “Flagpole Sitta.” Greg had arrived and was working at Slash Records now. Arena Rock was still alive. Superdrag would put out their records there. It would be indie and we’d be happier there. We were convinced that major labels sucked. All in all, it felt like a great situation.

Glover: I desperately wanted to sign Superdrag (at Slash), but I couldn’t convince the powers that be. I remained good friends with the guys, as well as their manager, Jake Ottmann, who let me hear the recordings for what was to be their third Elektra album. Having the opportunity to release my favorite band on my own label was truly a dream come true.

Ottmann: The guys had some great songs hanging around from a bunch of recording sessions. It would be great. We’d start over. It was settled. So, I did what any good manager does: I borrowed money from my girlfriend, and we went on vacation in Maine. We walked around the woods, and we got real cozy. Then we started to chat again about what I did for a living, and slowly I came to the conclusion that I probably couldn’t do it anymore. I bit down hard one day and made the decision to speak to the boys and tell them I couldn’t be their manager anymore. Unfortunately, what I didn’t expect was how damn good the album they had sat down to make with their old pal and now huge producer Nick Raskulinecz would turn out to be.

Davis: To Elektra’s credit, when they dropped us, they let us walk away with everything we had in the can and gave us money to go away. That enabled us to make some serious upgrades to the studio setup and rent enough outboard gear and mics to get us in the ballpark when Nick arrived.

Raskulinecz: The label giving the band their record back was a solid move. They could have easily kept the tapes they’d paid for up to this point and In The Valley of Dying Stars might never have been released. The band decided to use the rest of the recording budget to build a studio in Knoxville.

Coffey: In order for the plan to work, we had to finish the record, which meant we had to turn a practice space into a studio, get a bass player, get on a label and get back out on the road—in no particular order. It was not smooth sailing. But we did it.

Raskulinecz: It was really me, John and Don at this point. Brandon was showing up less. John was doing a lot of the guitar and bass.

Fisher: My involvement became necessarily limited. I had taken a day job in January 2000, and I couldn’t get to the studio till 7 p.m. most evenings. I don’t recall how many songs were tracked at Stealth, but when I came down, we’d focus on getting my guitars recorded.

Davis: The other thing kind of running in the background of all these other changes was the search for a new bass player. The decision was left up to Don, for obvious reasons. He went down to Manhattan’s one night to see Who Hit John play and asked Sam Powers if he’d be interested in joining Superdrag.

Powers: There were maybe 10 or 12 people in Manhattan’s that night. It was basically the band, a couple of our friends, plus wives and girlfriends. So that left the bartender—and Don. After the set, I remember talking to Don, and he told me they were looking for a bass player. It was really about the last thing I expected. I did have a job; it wasn’t my dream job, but I was the assistant to the general manager. Speaking to Don, I was flattered and stoked. I was a fan of Superdrag and I loved Don’s drumming. I had filled in for a missing bass player in one of Don’s old bands years before Superdrag called the Barnyard Martyrs. As far as Don’s drumming goes, it’s hard to have a pulse and not be a fan.

Coffey: How in the fucking world do you walk into a bar and ask Sam Powers to quit his nine-to-five job with no shows booked at all? I didn’t plan it. I didn’t go there intending to do it, I promise. I watched the motherfucker play, heard him sing and thought, “Oh shit, this could work.” But he’s gonna be gone in a few, I better ask, like, now. “Sure, talk it over with your wife.” Who does that?

“Shit! I better call Larry.” Larry Webman, our booking agent, is the fuckin’ man! This has nothing to do with the recording of In The Valley, but I just wanted to take this opportunity—they don’t come ’round too often—to say thank you. The ring on my wife’s finger … you know, that type shit. All we had to do was show up. Shit was pro! Always. Larry has a roster, and I ain’t gonna say we were nobodies, but we were on the lower end of the totem pole for sure. He came to the shows, hung around, even helped me sling merch a time or two. Solid. Last man standing. I can back that!

Davis: We were fans of Who Hit John; they played a show with the Used once that was kind of a fiasco. Well, really, the fiasco happened after the show.

Powers: My wife knew all the guys, but I don’t think we’d ever really hung out except to say a quick hello. That’s probably because of the infamous the Used/Who Hit John show where we brought our friend Johnny Concrete, who was obsessed with Hunter S. Thompson. It probably wasn’t the best fit. On a side note, Johnny Concrete features prominently in one of Nashville’s earliest transportainment stories, which also involves the lead singer of Ugly Kid Joe.

Davis: Brandon had worked with Sam’s wife, Laura, at Turtle’s, and I went to preschool with Laura’s brother, Jack. I had only met Sammy P. once before, on the front porch of the Longbranch. But he showed up to Stealth and played the set better than me.

Powers: I don’t remember the exact dates, but in between talking to Don and the first rehearsal, they played a show at the Library in Knoxville with the Gravel Pit from Boston. I made the trip with my wife to see the show and I remember talking to the guys briefly afterward. When I said goodnight to Don, he flipped me off but did it in the most loving way with a big grin on his face. The next thing I knew, I had a cassette with a bunch of songs on it and started learning them. I wore that cassette out, and since I had a two-and-a-half hour drive from Nashville to Knoxville, I would sing along, like I would do anyways. So when we set up for the first rehearsal, I wanna say “Baby’s Waiting” was one of the first songs we played. It’s natural to sing harmonies, and I don’t think we talked about it, but I just sang and I remember John looking over at me with a big smile on his face and then looking at Don, who had his familiar grin but no free hands.

Davis: One jam session was all it took. He was obviously the right guy—he nailed everything. I can’t tell you how much of a shot in the arm it was when Sam joined. A real breath of fresh air. He’s one of the funniest people I’ve ever known, and hell, we all could’ve used the healing power of laughter at that point. His musicianship, his writing, his singing, his presence onstage, the hang time—all that speaks for itself. Dude’s a badass. Not too long after this, we took the new lineup out on the road and tested some of the new jams. The one tour with the Sheila Divine where we had both Sam and Brandon in the van stands out in my memory as being one of the best.

Cortez: I was shocked and sad upon hearing that Tom had left the band, but Sammy P. fit in like a glove.

Fisher: Sam joined the band in the fall of ’99, and it seems like we got out on the road right after that—doing a handful of one-offs and a full tour near the end of the year. He fit in perfectly from the get-go, both musically and personally. All of those shows were a lot of fun, and it was cool to start working some of the Valley material into the set.

Davis: The time we spent finishing the record with NR at Stealth Studio was so much fun. He stayed with us. We had a real good time—too much of a good time.

Raskulinecz: We had so much fun—maybe too much fun. We spent maybe seven to 10 days finishing those songs. We worked non-stop, getting home as the sun was coming up every morning. Thanks for letting me sleep on your couch, Wendy (John’s wife). It really is a blur. All I know is we left there with a few of my all-time favorite Superdrag songs that we ever did together. You can feel the energy we had in those tracks to this day. The music, the hang, the tones, the vibe—and it was really a lot of fun to be doing this in Knoxville where it all started years earlier.

Powers: Once we started recording, it was really so much fun. For me, the tracking at Stealth felt very much like an audition, but once I passed that test, I really wasn’t worried about anything. The feel was so good, the vibe was great, everyone was really loose and having a really good time. I was just getting to know these guys, but they had so much history with Nick. I got to hear a lot of really funny stories. It was all very hopeful and positive. When I listen to the record, I hear that excitement every single time.

Fisher: I guess one thing about Valley that stands out for me personally is it was the first record we made after I got my Jazzmaster. I got it sometime during the Head Trip tours, and it immediately became my primary guitar. I got lucky—I went into a Knoxville guitar shop, and it had just come in on trade. It was still behind the counter, getting prepped to go out on to the floor. I played it and immediately asked them to hold it while I went home to grab a couple of guitars to trade for it. The paint had been stripped off before I got it, and the original knobs had been replaced with “witch hats.” I’ve left it exactly like I bought it. So as a consequence, Valley has a lot of Jazzmasters on it.

Davis: I was psyched to have Sam’s bass and background vocals on the record the rest of the way. I think “Lighting The Way” was the only one done at Stealth with me playing bass, and that was only because we liked the sound of the scratch bass. We also recorded “Keep It Close To Me,” “Goin’ Out,” “Ambulance Driver,” “True Believer” and the title track there.

Fisher: John played “Lighting The Way” with a Les Paul through a “cigarette-pack” amp. I always thought that was super-cool-sounding. I played my Yamaha SA-2000 on it—the first guitar I ever bought. I put it on layaway and made payments for maybe six months. Fun fact: The Yamaha would’ve been the guitar I played on the recording session that became Stereo 360 Sound, except that I broke a string and grabbed John’s Strat and used it instead.

Davis: The way it switches back and forth between the two studios in the finished master never bugged me; Nick mixed all of it to half-inch tape in the B room at Woodland. One night while we were there mixing, we went and saw Guided By Voices play at 328 Performance Hall. I couldn’t hear shit when we came back, but they were amazing.

Raskulinecz: Arena Rock gave us money to mix the record. Greg is cool as fuck. He gets it, and he was excited. We immediately went back to Woodland and mixed. It might’ve been four or five days. I think the two sessions fit together just fine. Listening back now, unless I really think about it, I don’t know which songs were done at what studio. They blended together well considering half the record was done in a big pro studio and the other half was done in a totally random space with no studio treatments whatsoever. The low end is the giveaway. We mastered the record, it came out, the band toured, the cycle continued.

Ottmann: I think the way the album starts with the chugging guitar on “Keep It Close to Me” is the leading edge to what turns out to be a vitriolic purge of every emotion the band and I felt following their Elektra experience. John’s guttural start, “I want rock ’n’ roll, but I don’t wanna deal with the hassle.” Having been on this ride, that line just digs deep. What follows is a cathartic release of emotions following the crushing exercise of trying to make it in the music business. As I listened to the album, I remember thinking that I’d never recover from walking away from the band. I was so bummed. John’s lyrics now had real purpose. They were unbridled and could dig deep into their roots and make music they wanted. Nick was a rock producer with pedigree now; he’d go on to win a Grammy with the Foo Fighters, but he was already deep with Dave Grohl and making amazing rock records. Brandon Fisher’s My Bloody Valentine-style wash guitar could fully take hold. These songs were fully realized. I was on the one hand smitten with the band, and on the other hand bitter with jealousy. How could they make such a powerful album without me? I would be left behind.

Fisher: I love the vibe on the title track. One of my favorite parts of the record is when the chorus kicks in: “Can you hear the sound?” with the stacked vocal harmonies.

Glover: I remember telling people that I believed I’d just released one of the greatest rock ’n’ roll records ever. Two decades later, I still firmly stand by that statement. “True Believer” is my favorite. I think it could be John’s best vocal performance on any Superdrag song. It should probably be played when they lay me in the ground.

Fisher: By mid-2000, I’d made the decision to stop touring. It was never about the music, which I was proud to be involved in, or the other guys, who were and still are some of my closest friends. I just wasn’t able to spend a substantial part of the year away from home anymore. So I was no longer in Superdrag. It was the right decision for me, but I do wish I’d gotten to play more shows with John, Don and Sam, and I kinda regret missing the Japanese tour. Even though I departed from the band shortly after its completion, In The Valley Of Dying Stars is very special to me. I was always stoked with the record we made—I love the way it sounds, and many of my favorite Superdrag songs are on it. Many thanks to everyone who was involved with it and to everyone who has cared about the music through the years.

Pappas: In The Valley Of Dying Stars turned out to be my favorite Superdrag album, and I don’t even play on it. I became a fan and started to go to Superdrag shows. I kept working on my band Flesh Vehicle. Now it’s Tom Pappas Collection.

Cortez: The production and sound on Valley just blew me away. The songs need no adjectives. OK, perhaps one: brilliant. I worked that record like it was my own and went to the shows whenever I could, Elektra be damned. Everyone involved with Superdrag should be proud as fuck of those records. Head Trip and Valley haven’t gone away, nor have they diminished over time. Quite the opposite. I go on a lot of music forums and see the band and both those records being praised by new and old fans alike. I’m so honored to have been involved in my small way.

Ottmann: If I were stranded on an island and had one song to pick, it very well might be “Bright Pavilions.” That song, to me, wraps my whole Superdrag experience into one three-minute package: the drugs, the excitement of winning and the halcyon rush of success in music. I still listen to this record. It’s my favorite.

Coffey: I hope folks still get a kick out of it. Thanks for giving a fuck—we had a great time making it. I believed it was a good collection of songs, and I still do. The Superdrag company line was, “We’re gonna shove it up their ass!” Truth is, I was terrified. That’s an understatement. If the drums on In The Valley of Dying Stars sound like I’m playing as if my life depended on it, it’s because it did.

Raskulinecz: The song “In The Valley Of Dying Stars” says it all: “Can you hear the sound?’’ I can—and always could. Valley will always have a special place in my heart. Those are some of the best songs John and the band ever wrote. Twenty years later, a lot of Superdrag fans say it’s their favorite album. That means so much to me. And we did it together. I consider it to be the first real record I produced. I told John recently that I hope the last record I make is with him. It could be called Return To The Valley Of Dying Stars. Knowing John, he’s probably already written it.

Davis: In The Valley Of Dying Stars is my favorite Superdrag record. It kind of has to be. No disrespect to Jerry Finn. Never. Nothing but the deepest respect. But song for song, this is the best album we ever put together. I wouldn’t change anything about it. That was the problem back then, I guess. I couldn’t change a word of it. I knew what it had to be. Some of the lyrics came from nightmares. I borrowed the Oswald imagery in “Gimme Animosity” because I felt like my brains had been blown out by grief. The record never would’ve happened without the others, Don especially. He had enough energy and gumption for both of us. Those guys carried me through some things. They’re the brothers I never had. I love every one of ’em, and I always will. I was honored to ride with every single person involved with this album. It couldn’t be stopped.