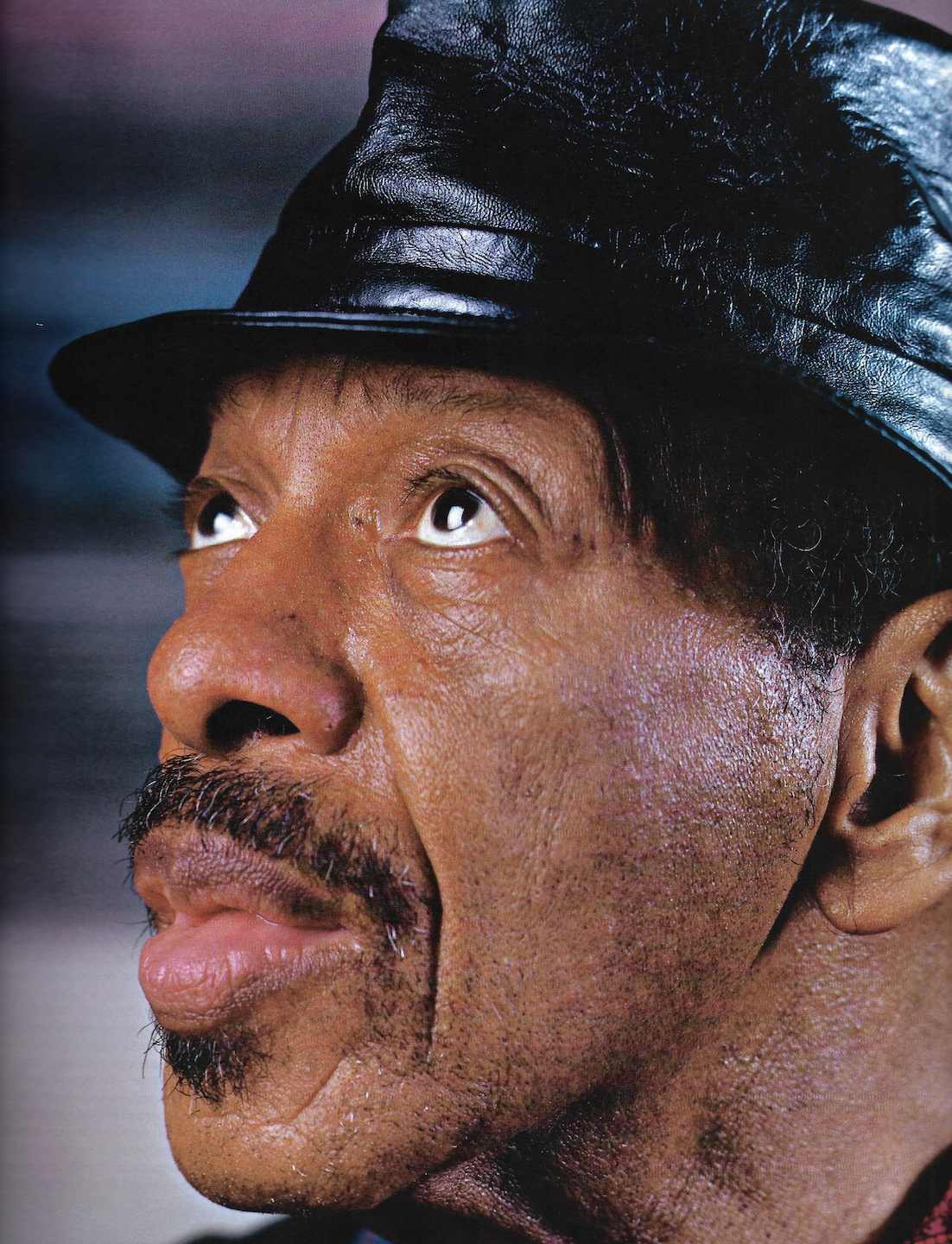

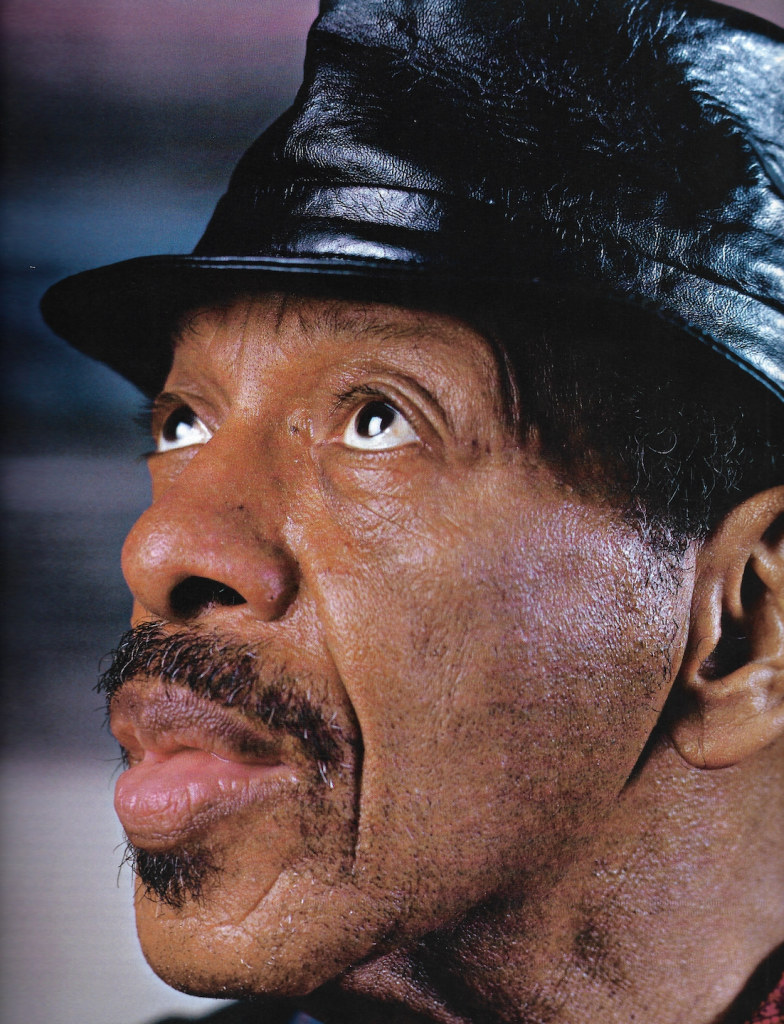

MAGNET’s Mitch Myers recounts the history of a free-jazz pioneer and his Prime Time lessons on sound grammar. Photo by Nicholas Burnham.

It’s 2006, and here he is, dressed impeccably in a tailor-made suit, holding court at J&R Music World in Lower Manhattan, signing copies of his latest CD for devoted fans. Earlier in the day, he taped a segment for Black Entertainment Television and made an appearance on local public radio station WNYC. There he is again, engaged in a face-to-face listening session with a New York Times reporter and, later, doing an interview with NPR’s Morning Edition.

No, we’re not talking about some veteran rock star or hip hop’s latest mogul/producer. We’re referring to Ornette Coleman, one of the most influential jazz artists to emerge in the last century. And he wants to connect with you—right now.

It’s hard to imagine that, at the age of 76, Coleman would desire so much exposure, but he does. To be sure, he already possesses one of the most distinctive instrumental voices in jazz. (Besides alto sax, Coleman plays violin and trumpet.) Still, with the unveiling of Sound Grammar, his first new album in more than a decade, and the repeated touring of Europe with his latest band, you just might call it a comeback.

“Ornette used to not want to talk to the press or anything like that,” says James Jordan, Coleman’s older cousin, producer and manager. “But now you can’t believe the photo shoots and interviews he’s had. We really have to limit it because it’s grueling to be on the road, talking all day and playing all night.”

Preparing for yet another European tour, Coleman gently puts his band through their paces during a rehearsal at his Midtown Manhattan apartment. His home is decorated with fascinating artwork, including original paintings that have graced the covers of his albums and, on opposite walls, two huge photographs of Sitting Bull. The doorbell buzzes frequently as friends and fans come and go, but Coleman hardly seems to notice. He’s preoccupied with transposing his tunes into different keys and philosophizing about life and music, which are more or less the same thing as far as he’s concerned.

Born March 9, 1930, to a poor family in Fort Worth, Texas, Coleman was seven when his father died. Young Ornette had to help earn money so his family could get by, and the gentle, quiet child had a tough time growing up in segregated Fort Worth.

“My mother loved coffee,” he recalls. “She would tell me, ’Junior, go up to Leonard’s and get me a can of coffee.’ So I would go up there, and a little white kid would beat me up and throw the coffee on the ground. I’d come home crying, and my mother would tell me, ’Go back, do it again.’ Lord, I was going to get an ass kicking—either from her or him, I didn’t have any choice! I grew up with hardly any men in the house. I was supposed to be the man. So I kept doing that until I grew out of getting an ass kicking. But I learned a lot being in a mature situation, because of race and that kind of stuff.”

After a jazz band performed at his school, 12-year-old Coleman asked his mother for a saxophone. “She said, ’Yes. If you find a job and make some money,’” he says. “So I got my shoeshine box and started going out, and I’d give her all the money. About a year and a half later, she said, ’Look under the bed.’ There was a saxophone. I thought it was a toy, and I just played it. I’m self-taught. I didn’t know anything about it being real, so I just played without even thinking about it. I got so where I could get a band together and started helping my mother pay the bills. I had lots of inspiration because there were guys older than me who were playing rhythm and blues in nightclubs.”

Still in his early teens, Coleman convinced his mom to allow him to go out at night and perform at honky-tonks—with his sister Truvenza as chaperone—to earn much-needed cash. Like many of his peers, he started out playing danceable jazz and honking R&B, only to fall under the spell of the revolutionary sounds of bebop.

“I was getting a little older when the style of bebop came out,” says Coleman. “Then, I taught myself how to write music, because I really wanted to be a part of that scene. I used to like a tenor player by the name of Gene Ammons; I thought he was God.”

After graduating high school, Coleman was offered scholarships from black colleges, but he declined. Still eager to escape Fort Worth, he took a gig playing tenor sax with Silas Green’s traveling minstrel show in 1949. Coleman’s sound was already drifting outside of the tonal mainstream, and with his long hair and vegetarian diet, he didn’t fit in with the rest of the troupe. Touring the Deep South, he found his surroundings even more hostile than they’d been in Fort Worth. The police in Natchez, Miss., accosted him, and after a show in Baton Rouge, he was badly beaten by a group of blacks, mainly because of his beatnik appearance. Adding insult to injury, they destroyed his saxophone.

Coleman convalesced in New Orleans, living with a family of musicians before returning home. The music of altoist Charlie Parker consumed him. Coleman could play just like Bird, and this was no small accomplishment. But just as he’d outgrown the structures of traditional jazz and R&B, Coleman began stretching the boundaries of his beloved bebop and forged a freer, more unconventional style of jazz. His sense of melody, harmony and time became increasingly offbeat, and musicians accused him of playing out of tune.

Speaking with Coleman today, you can see that he remains a vulnerable and gentle person. It’s not hard to imagine people taking advantage of this sensitivity, but beneath his tender nature is a focused determination that’s allowed him to pursue his musical ideals.

Coleman explains his transformation this way: “I was playing rhythm and blues. When I heard Charlie Parker, I said, ’Wait a minute, that’s got to go!’ Then, all of a sudden, I outgrew that! Because it all became kind of stylistic, and I’m convinced that style will never dominate ideas.”

Coleman’s ideas came to fruition in Los Angeles during the 1950s. Although the West Coast jazz scene was better known for the smooth, swinging sounds of Chet Baker and Gerry Mulligan, there was an undercurrent of adventurous players like Charles Mingus and Chico Hamilton. Still, almost single-handedly, Coleman launched free melodic improvisation in L.A. and, eventually, the world.

Following his recovery in New Orleans, Coleman returned to Fort Worth in 1950 but found it very difficult to fit in. Eventually, he joined bluesman Pee Wee Crayton’s band, which took him to L.A. There, he ended up in the down-and-out Morris Hotel on Fifth Avenue, where the neighborhood’s glory days had passed and the street was something of a skid row. As before, he was regarded as a freak and derided by his fellow jazzmen. Broke and living on care packages from his mother, he even lacked the funds to keep his saxophone in good repair. But Coleman kept striving to develop his own sound, and he never sold out.

“That’s one thing that I escaped,” he maintains. “I didn’t ever use what I was doing to survive. I always wanted to get better in the direction that I was going, and I’m still that same way right to this very day.”

Coleman’s luck gradually began to turn in L.A. He was still having trouble finding opportunities to perform; for a time, he worked as an elevator operator at Bullock’s department store. When things were slow, he’d stop the elevator and take a few minutes to read books on music theory and harmony. Around this time, he began encountering musicians who would help him take his ideas to the next level.

Eddie Blackwell, a drummer from New Orleans who stayed at the Morris Hotel, wasn’t put off by Coleman’s approach to improvisation. Coleman would eventually move into a house with Blackwell in Watts, a predominantly black South Los Angeles neighborhood. He developed a social network and, in 1954, married 18-year-old poet/musician Jayne Cortez, who gave birth to their only child, Denardo, two years later. (Coleman and Cortez divorced in 1964.) He was also rehearsing with friends from Texas, L.A. and New Orleans. When Blackwell went back to Louisiana in 1956, drummer Billy Higgins was already set to take his place. Higgins was a cohort of Don Cherry, a bop-inspired trumpeter from Watts who became an integral part of Coleman’s group. Not much later, a young bassist named Charlie Haden completed the inner circle.

In 1958, Coleman and Cherry auditioned for Lester Koenig, who owned L.A.-based independent label Contemporary Records. Playing in cracked unison, Coleman and Cherry sounded like expressive musical savants, and their instrumental voices wandered all around the music’s tonal center, subverting the concepts of rhythm, melody and pitch. Intrigued by their off-kilter approach, Koenig gave Coleman a recording contract. Coleman titled his debut Something Else!!!!, and that’s exactly what it was. His early compositions still had plenty of formal jazz structure, but they stretched the constraints of bebop.

On 1959’s Tomorrow Is The Question!, Coleman and Cherry extended their harmonic patterns even further, but the album featured a bop-conformist rhythm section made up of session musicians. Meanwhile, Coleman’s own quartet—featuring Cherry, Haden and Higgins—had coalesced into a dynamic and innovative force.

Some critics dismissed Coleman and Cherry as aesthetic primitives unable to play in conventional modes. This impression was exacerbated by the fact that Cherry played a small Pakistani pocket trumpet and Coleman was using an inexpensive white plastic alto saxophone. The two wielded their quaint instruments in all seriousness, but according to skeptics, they were just unschooled eccentrics messing around with toys.

“When I hear people say that Ornette is a primitive musician, it’s totally insane,” says Jordan. “We were in the same high school band and reading some very sophisticated music. There was a really good music teacher, and we competed in concert playing. We grew up in segregated Fort Worth, so everybody our age was at the one high school; it was that competitive. You had to be able to sight read, count and be up to speed.”

After the two LPs on Contemporary, Coleman signed to Atlantic Records and recorded 1959’s epic The Shape Of Jazz To Come. Coleman and Cherry continued their freeform razzle-dazzle, and the rhythm section of Haden and Higgins was finally showcased on record. Haden’s bass playing was no less than volcanic. With Higgins’ rippling percussion, the group blazed through up-tempo numbers and lavished empathically over Coleman’s idiosyncratic ballads.

Momentum was building when Coleman received praise from authorities such as Modern Jazz Quartet leader John Lewis and conductor/arranger Gunther Schuller. When Lewis awarded Coleman and Cherry a three-week scholarship to the Lenox School of Jazz’s annual summer program in western Massachusetts, a firestorm of controversy ensued. That debate was nothing, however, compared to the fuss that was raised when Coleman’s quartet headed east to perform at the Five Spot Café for their New York debut on Nov. 17, 1959.

The Five Spot was a low-rent space with a high-end reputation located in Greenwich Village at the corner of Cooper Square and St. Mark’s Place. Pianist Cecil Taylor played at the Five Spot, as did Charles Mingus; Thelonious Monk’s group with John Coltrane enjoyed a six-month residency at the club in 1957. Coleman had to scrape together the funds for his band to travel from California to New York, but his two-week engagement garnered so much attention that the gig expanded to a two-and-a-half-month run.

“I got a call from this writer named Martin Williams who said he could get me a job at the Five Spot that was paying about $15 a night,” says Coleman. “I stayed there for months, but everybody thought that I was out of my mind. They said, ’You can’t play—there’s no way you can play like that.’ Oh man, it was terrible because nobody encouraged me. I guess they thought I was just being exploited, but I was really getting more and more into it.”

The controversy filtered down to the jazz journals, and everybody was weighing in on Coleman’s band. Even Leonard Bernstein, then employed as the New York Philharmonic’s music director, sat in with the group. Miles Davis, the reigning king of cool, derisively said, “Hell, just listen to how he writes and how he plays. If you are talking psychologically, the man is all screwed up inside.” Drummer Max Roach reportedly castigated Coleman, while trumpeter Roy Eldridge exclaimed, “I listened to him all kinds of ways. I listened to him high and I listened to him cold sober. I even played with him. I think he’s jiving, baby.” Coleman may have been emotionally bruised by the angry reactions to his music, but he stayed busy, entering into one of the most prolific and creative phases of his career.

While old-school jazz aficionados were split on Coleman’s validity, young white bohemians were drawn to his music, and his shows at the Five Spot sold out almost every night. The band chose to stay in New York, and when Higgins had his cabaret card revoked, denying him the right to perform in Manhattan nightclubs, Eddie Blackwell returned to the fold. Using Higgins or Blackwell (and sometimes both), Coleman made eight excellent records for Atlantic, including 1959’s Change Of The Century and 1960’s This Is Our Music.

Despite his contributions to modern and free jazz, Coleman is still partial to the classic composers of his generation. “I started composing music and I haven’t stopped trying, because this is the opportunity for people to be interested in what you do,” he says. “That’s not as plentiful in jazz as it used to be. When you hear Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Miles Davis or Elmo Hope—lots of people who were into writing instrumental music on the level they are—you don’t hear that very much anymore. I don’t know why, but there’s nothing in the way of it.”

After being dropped by Atlantic due to poor sales, Coleman struck back by renting New York City’s historic theater-district venue Town Hall and promoting his own concert in 1962. Coleman paid all the musicians himself and even put up the posters around town publicizing the event. His seminal quartet had dissolved by this time, and the evening at Town Hall showcased a string quartet, an R&B group and Coleman’s new trio with bassist David Izenzon and drummer Charles Moffett.

The string ensemble performed Coleman’s first foray into the classical realm (a composition titled “Dedication To Poets And Writers”), but the concert punctuated another, more dramatic shift. Coleman broke even financially at Town Hall that night, but he was tired of working for little money and playing inhospitable jazz clubs. He set out to redefine himself as a concert artist and tripled his performance fees. As a result, Coleman barely worked for years, since few promoters in America were willing to match his newly inflated price.

After an extended hiatus, Coleman finally took his trio to Europe. Still making the transition from jazz clubs to the concert hall, he booked a big show in London. Unfortunately, the British Ministry of Labour labeled him a “jazz musician” and refused to let him perform unless an equal number of British artists were allowed to play in the U.S. Coleman circumvented this political quagmire by composing another piece of classical music to be performed by a woodwind quintet. Coleman was again compelled to finance the show on his own, and the new composition, “Forms And Sounds,” was performed in 1965 as part of the Fairfield Hall concert in the London suburb of Croydon.

“Music is something that is 24/7 in Ornette’s life,” says Jordan. “He’s always discovering something, and learning to him is something that goes on and on. You learn something, and that leads you to something else. There’s no stopping and saying, ’Oh, I got it.’ Learning is endless. The more you know, the more you know you don’t know.”

Aside from “Sound Grammar” being the name of both Coleman’s record label and latest album, the term has a third meaning. It refers to the idiosyncratic philosophy that Coleman used to call his “harmolodic” theory. While he claims to have started working on harmolodics as far back as the 1950s, Coleman formally introduced the concept in 1972 on the orchestral Skies Of America. The album remains unwieldy and musically uneven, but you can hear Coleman improvising fearlessly alongside the London Symphony Orchestra. The piece has endured, and he’s still performing the controversial composition 34 years after its debut. The idea of harmolodics, however, has been the source of great debate and confusion.

“Harmolodics,” Coleman once said, “is where all ideas—all relationships and harmony—are equal in unison.” The notion of harmony, melody and rhythm all existing independently (and experienced simultaneously) is the unshackling of traditional music structure—which frees the players to complete their musical thoughts and conversations regardless of song form. It also encourages the musicians to listen to each other and play “in the moment” at all times.

Those who claim to understand harmolodics are, for the most part, musicians who’ve played with Coleman. Cherry defended it, and guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer adapted to it. Coleman doesn’t use the word harmolodic as much as he used to, and perhaps changing the conceptual term to “sound grammar” is just another part of his latest push for commercial acceptance. In any language, Coleman’s sonic philosophy requires a great commitment from his followers.

In 1973, just a year after Coleman recorded Skies Of America, he sought a very different musical experience: playing with the Master Musicians of Joujouka in Morocco. Expatriate writers William Burroughs and Paul Bowles had previously witnessed the spectacle of the Joujoukan musicians, and the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones made a pilgrimage to Morocco to record the Master Musicians in 1968. Coleman was brought to North Africa by journalist/musician Robert Palmer, and the ecstatic marathons of Moroccan music making were unlike anything he had experienced.

Occasionally mirroring Coleman’s harmolodic ideas, the Joujoukan masters moved with unspoken unity across tempos, rhythms and melodies. The music also had the power to heal and soothe, which Coleman witnessed firsthand. The tribe had its mystical side, and a few tricks were played for the benefit of the visiting Americans, but the impression the sacred music made on Coleman was far more significant. Brief portions of the encounter can be heard on 1973’s Dancing In Your Head, although most of the Morocco recordings have remained unreleased.

“We were in Joujouka, and I saw a woman,” says Coleman. “I don’t know if she was drunk or whatever, but she was out of her mind. They just stood right in front of her and played. Before she knew it, her face changed—her spirit, everything changed—just from that sound. I said, ’Oh, my goodness! You can do that!’ But to see it in a human condition, it blew my mind. She got so calm, and it looked like none of that had ever happened. Well, music’s got that in it, and it’s nothing but sound.”

Not long after playing with the Master Musicians of Joujouka, Coleman decided to go electric. He was stimulated by the sounds of the electric guitar when jamming with James Ulmer and set out to organize a band of young, plugged-in players. His 1975 harmolodic group, Prime Time, featured electric guitarists Bern Nix and Charles Ellerbee, bassist Rudy McDaniel and drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. Soon, Denardo Coleman—Ornette’s son, who made his recording debut with his father in 1966 at the age of 10—joined as the band’s second drummer.

Inspired by tapes of the Joujouka encounter, Prime Time created a discordant stew of electric jazz fusion. Dancing In Your Head and Body Meta both signaled the change, and again, Coleman’s alto sax came slicing through. Prime Time thrived for more than a decade, touring and releasing albums. The late ’80s saw Coleman collaborating with guitarists such as Pat Metheny and Jerry Garcia. This was followed by another period of relative silence; in 1995, Coleman formed the Harmolodic label, re-releasing Body Meta and Soapsuds, Soapsuds (a beautiful duet LP with Haden). After 20 years of harmolodic funk, his electric band was still changing, and Coleman introduced a new Prime Time album, Tone Dialing.

In 1996, Coleman celebrated a return to acoustic music with twin discs Sound Museum Hidden Manand Sound Museum Three Women. The Sound Museum albums have the same tunes and are played by the same musicians. The repetition of the material was intended to display the democratic freedom that can be achieved when interpreting music using Coleman’s harmolodic—make that “sound grammar”—approach. By the turn of the millennium, Coleman was presenting a three-headed live show. In a single night, he’d take the stage with his Global Expression project (a drone-oriented group with Indian musicians), then perform a piece called “Freedom Symbol” with a 20-piece chamber ensemble, then end with a set from his trio with Haden and Higgins.

So there he is, sitting in his apartment, patiently explaining his life, his work and his eccentric theories. On Sound Grammar, Coleman’s crying alto is immediately identifiable and perhaps even stronger than it was 40 years ago. The album is a live recording, and it displays his quartet in a particularly democratic mode. Bass players Greg Cohen and Tony Falanga work in dramatic counterpoint, while Denardo operates almost vertically on the drums. For a recent concert at Carnegie Hall, a third bassist, Al MacDowell (once a member of Prime Time), joined the group. Personnel changes are inevitable, but for Coleman, it’s always about the music.

“If there weren’t any musical keys, you’d have pure sound grammar,” he says. “If there wasn’t any definite resolution of the idea, you’d have pure sound grammar. If there wasn’t any time representing speed for resolution, not only would you be able to play more ideas without filling up bars, but they would eliminate you needing bars.”

As confusing as this may be, there’s little doubt as to Coleman’s cultural significance. He still commands big money when appearing in concert, and whenever he’s slated to perform, he composes new material for the show. Through it all, Coleman has been searching, moving forward, refining his sound, expanding his theories and reorganizing his syntax. He’s so immersed in the process that when he talks about music, he assumes the listener is right there with him.

“I’ve learned that changes lead you to how it goes, but it doesn’t lead to the idea,” he says. “So I’ve been working on the idea. To me, the purest idea in music is modulation, without disturbing the key. In other words, most music is translated, but the melody cannot be translated, only the sounds. That hasn’t happened yet. But it’s coming. Oh yeah, I’m right on it. I’m definite on it.”

There’s a humanist element to Coleman: empathy in his music and his existential philosophy. He’s listening and looking for a personal connection, and the confluence he yearns for is revealed every time he plays. No matter where he is in the world, Coleman is seeking to bond with other people. Through his music, he is striving to attain a state of grace.

“Right now, at this very moment, I’m struggling to work my spirit and my brain and my intelligence,” says Coleman. “I’m struggling with it in relationship to sound. What it does for me now is what it did for me 30 years ago. It will come when it comes. I could get going there and I know the notes—you could stab me and I would still know what the notes are—they’re just imprinted.”

No longer the jazz firebrand, Coleman is now an enigmatic elder statesman. Most of his early disciples have passed away, including Don Cherry, Eddie Blackwell, Billy Higgins and, in September, saxophonist Dewey Redman. Just as our interview is concluding, Charlie Haden and his wife stop by for a visit. The bassist is in town with his own band, playing at a Manhattan club for the week. It’s the second time in two days that Haden has come to talk with Coleman.

You can only wonder what they discussed.

Haden passed away in 2014, Coleman a year later.