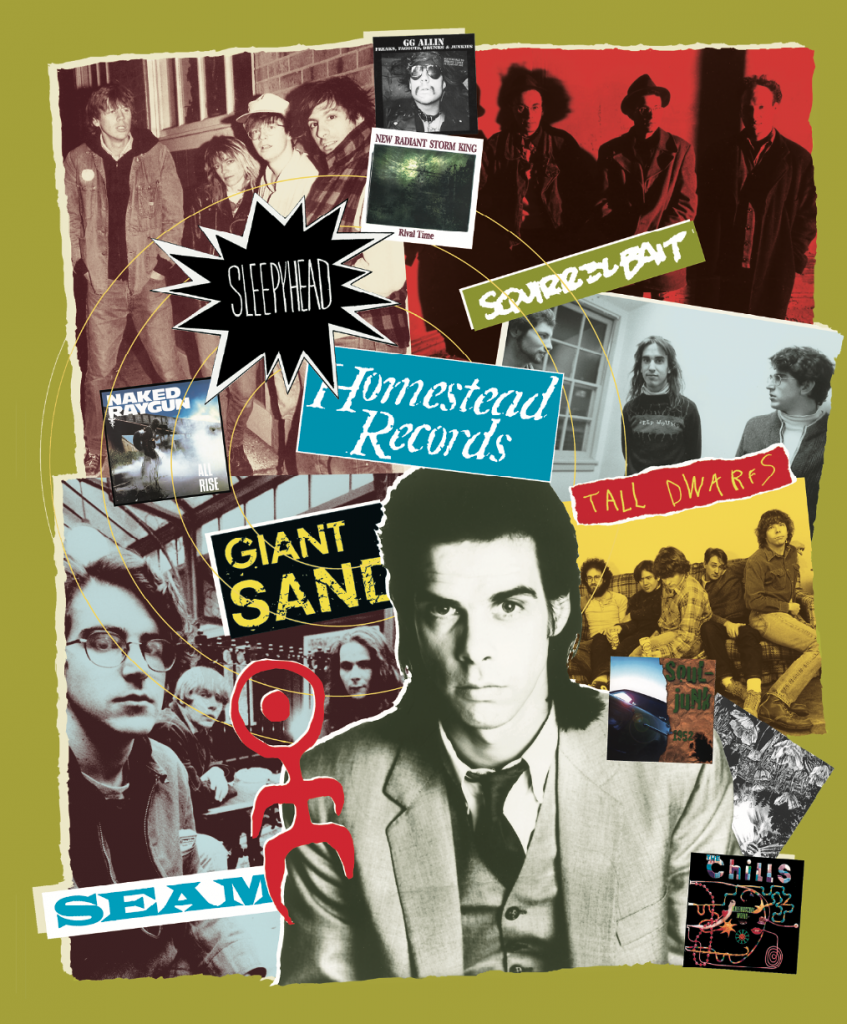

Homestead Records released albums by Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Sebadoh, Big Black and Giant Sand. The story of the label that pioneered—and some say plundered—indie rock. By Matthew Fritch

Sub Pop sold grunge and SST peddled punk, but Homestead Records gave you indie rock. From 1983 to 1996, the Long Island, N.Y., imprint left its logo all over the artifacts of alternative music: Dinosaur Jr’s first album. Sebadoh’s first three albums. Sonic Youth’s second album. From the provocateurs (GG Allin, the Frogs) to early-period Seattle scenemakers (Green River, Screaming Trees), from European exports (Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, Einstürzende Neubauten) to NYC free-jazz figureheads (David S. Ware, William Parker), Homestead’s discography documented it all.

Homestead and its parent company, music distributor Dutch East India Trading, was also a breeding ground for tastemaking figures of the underground. Among those who passed through the corporation’s ranks were the future principals of Matador Records, the founders of respected independent stores Other Music and Sound Exchange, an editor of Blender and Spin—even a member of Helmet.

Yet few are eager to canonize Homestead alongside upstanding indie stalwarts Dischord and Touch And Go. In fact, mere mention of the label’s name to some former artists and employees elicits memories of mismanagement, malfeasance and missed opportunity. History isn’t always pretty, and there are bitter feelings scattered along the trail Homestead blazed in the ’80s.

Back in the mid-’60s, the other kids in Barry Tenenbaum’s Long Island neighborhood may have been earning extra cash by mowing lawns or delivering newspapers. Tenenbaum, an avid Beatles fan, began operating a music mail-order business from his bedroom at age 14. Lord Sitar Records—LSR, for short—was named in honor of George Harrison’s rumored alter ego, and Tenenbaum kickstarted the company by disguising his voice over the phone, pretending to be older and importing Beatles records from England to sell at a profit.

Tenenbaum’s business soon expanded beyond the Beatles catalog and mail order when he discovered he could buy albums from international companies such as EMI for less than domestic prices and then distribute them to local record stores. Not long after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School in 1980, Tenenbaum and LSR were forced to adapt: An amendment to the Copyright Act of 1976 barred companies such as LSR from importing music whose rights already belonged to U.S. labels. Having built up an extensive distribution network under the company name Dutch East India Trading, Tenenbaum began licensing records for release. The burgeoning punk and new-wave scenes in both the U.S. and U.K. created a new niche market for Dutch East, which also began putting out vinyl versions of bands’ finished tapes. By 1983, the vinyl-releasing arm of Tenenbaum’s company had turned into Homestead Records, with Dutch East domestic buyer Sam Berger falling into the role of the label’s first manager.

Berger was responsible for Homestead’s first clutch of releases, which include records by two-chord Boston punks the Dogmatics and Columbus, Ohio’s Great Plains, a band featuring future members of the Gibson Brothers and Thomas Jefferson Slave Apartments. Great Plains keyboardist Mark Wyatt remembers the mid-’80s—the predawn of alternative rock—as a challenging time for left-of-center bands.

“It was really hard to play out,” says Wyatt. “No Internet, no MySpace, nothing but me on the phone all the time. And I mean all the time. We were existing in an extremely marginalized scene, where there was virtually no mainstream press for what we were doing, no radio except for college radio and certainly no TV.”

Another of Homestead’s early releases came courtesy of Big Black, a noisy group of Chicago art brutes led by caustic zine columnist Steve Albini. Circumspect about signing with a label in the first place, Albini—who now fronts Shellac and has recorded albums by Nirvana, the Pixies, et al—opted to license Big Black’s albums to Homestead in order to retain ownership of the music. Based on his alleged experiences with Tenenbaum’s bookkeeping, it was a wise move.

“My favorite retarded trick is he would make the numeral and literal amounts of the check different, so our bank couldn’t cash it,” says Albini. “It was like dealing with a small child who’s trying to hide cookies under his pillow. I’m sure it did earn him a small aggregate profit, being so duplicitous about everything. But it seems like so much work to be that devious about small amounts of money.”

Albini dismisses the notion that human error was to blame. “You can’t have a mistake on every single statement without it being intentional,” he says. “It’s impossible. Just by chance, you’d get one of them right, you know?”

Berger left Homestead in the summer of 1984 and recommended as his replacement Gerard Cosloy, a University of Massachusetts-Amherst dropout, record-store clerk and publisher of bitingly funny underground-rock zine Conflict. Cosloy, an astute music fan with zero experience running a record label, accepted the job. He later learned that no fewer than four people had turned down the position before him.

“I was either label manager or president or who knows,” says Cosloy, Homestead’s sole employee for much of the period between 1984 and 1990. “I was doing pretty much everything you can imagine: signing bands, doing the radio and press stuff, packing promos—rather frantic stuff.”

Cosloy’s tenure would prove to be a classic period for Homestead. Thanks to connections forged through Conflict, Cosloy seemed to have an ear to the ground in every city, not only recruiting local upstarts Sonic Youth and Swans, but also reaching out to sign or license bands from Cleveland (My Dad Is Dead, Death Of Samantha), Seattle (Green River, Screaming Trees, Beat Happening), Louisville, Ky. (Squirrel Bait, whose members went on to form Slint and Gastr Del Sol) and even New Zealand (Chills, Tall Dwarfs, Verlaines). While Homestead quickly earned a trendsetting reputation, Cosloy was often overwhelmed at the business level.

“We were psyched to be on this label that seemed to be the best one out there aside from SST,” says Mudhoney frontman Mark Arm. Arm was then a member of Green River, which had been tipped to Cosloy by zine colleague Bruce Pavitt, publisher of Seattle’s Sub Pop. “At first, Gerard would answer the phone when I called; then after a while, he just kind of stopped answering the phone. We could never get a straight answer on when the record was coming out.”

In fairness to Cosloy, Homestead was not only low on manpower, it was low on funding. Sonic Youth’s recording budget for Bad Moon Rising was reportedly a mere $800; Sebadoh was given $1,300 for III. Bands could expect a few posters to be made and some advertisements to be placed in zines; Cosloy estimates most marketing budgets to be in “the mid three figures.” In 1987, Craig Marks (future editor of CMJ, Spin and Blender) joined Cosloy in running Homestead. Marks signed Giant Sand, a cash-strapped band that was nearly at the point of hanging it up.

“Craig bought me an old Fender Deluxe reverb amp for $75 plus an ’81 Honda Civic to tour in for $2,000,” says Giant Sand leader Howe Gelb. “He put it all on his credit card.”

Still, it was Cosloy who steered Homestead through its most interesting times. Gross-out punk legend GG Allin (birth name: Jesus Christ Allin) was a bit past his prime when Cosloy signed him for two albums, 1987’s You Give Love A Bad Name and 1988’s Freaks, Faggots, Drunks & Junkies. Allin, who died of a heroin overdose in 1993, had gained infamy for, among other things, his habit of defecating onstage and throwing his feces at the audience. Around the time of Freaks, Allin agreed to appear on The Morton Downey Jr. Show for an episode dedicated to the topic of “shock rock.” Allin never made it to the WWOR-TV studios.

“He and his band were arrested that afternoon for laying waste to the Meadowlands Red Roof Inn, where the TV station had generously put them up for the evening,” says Cosloy. “Supposedly, they knocked over the lobby aquarium before they even checked in. On that night’s show, an outraged Morton Downey Jr. showed photographs of what appeared to be an unmade Red Roof Inn bed—to illustrate just what sort of animals he was dealing with. Secaucus police arrested GG the next day. He was hiding in the studio audience of WWOR’s (morning show) People Are Talking.”

Cosloy also caught flak for the Frogs, the Milwaukee brother act of Dennis and Jimmy Flemion, whose It’s Only Right And Natural album was issued by Homestead in 1989. Over-the-top songs that center on sexual stereotypes, such as “Homos” and “Been A Month Since I Had A Man,” touched a nerve with both conservatives and those who deemed the non-gay Frogs as homophobic.

“As an East Village resident who encountered all kinds of humans on a daily basis, I couldn’t imagine that anyone would confuse the Frogs’ queers-from-outer-space storytelling with real life,” says Cosloy. “But sure enough, some people told me they couldn’t write about—or play on the radio—that ‘fag’ record.”

Homestead’s oddball acts didn’t generate a lot of sales, but they did help to cement the label’s forward-thinking reputation. While Tenenbaum stuck to the bookkeeping and contractual aspects of the business, Cosloy and a cadre of Dutch East employees—Homestead shared office space with its distributor in various locations in Nassau County, Long Island—fostered a record-hound culture within the company. Dutch East’s employees included, at various points, Chris Lombardi and Patrick Amory (now Cosloy’s cohorts at Matador Records), Craig Koon and Jeff Gibson (of Austin’s Sound Exchange and NYC’s Other Music record stores, respectively), future Helmet guitarist Peter Mengede and many others who still work behind the scenes in the music industry.

“Barry was able to attract a great, versatile crew of low-salaried, insane young people,” says Cosloy. “Though Barry was initially jazzed at all the positive attention things like Sonic Youth or Big Black or Big Dipper brought to Dutch East, he also came to regard the bands as annoying enemies. Either they were bound to complain about low sales, demand more dough or leave because of dissatisfaction with both of the above.”

In 1986, Sonic Youth left the label to sign with SST. Shortly thereafter, Dinosaur Jr also defected to Homestead’s West Coast rival. Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore recalls some bad vibes during a business meeting with Homestead management: “Bob Bert, our drummer at the time, said we have an important meeting with Barry, and that we should tape it. It wasn’t like we were trying to sneak the tape in and record the meeting. We were going over some brass tacks with Barry, who’s a totally old-school business dude … Talking to this guy was like talking to the parents in the Peanuts cartoon. It was all ‘wah-wah-wah.’ I could see the look in his eye when he saw the red light on the Walkman. He was completely freaked out by it. He made us turn it off, and the mood in the room just turned nefarious.”

Says Cosloy, “For a very long time, I had coped with some of Dutch East’s ethical lapses and poor treatment of employees, believing naively that as long as I was doing a good job, I’d be helping the bands more than hurting them. It got to the point where I no longer believed that.”

In January 1990, Cosloy and Marks tendered their resignations. “Barry didn’t ask us why, nor did he try to talk us out of it,” says Cosloy. “I suspect he was relieved; certainly it saved him the trouble of firing us. I gave him two weeks’ notice. He told me to clean out my office two days later.”

With Nirvana’s Nevermind opening the floodgates for alt-rock to pour into the mainstream, 1991 was the year punk broke—everywhere but at Homestead. According to Ken Katkin, a former college-radio DJ at Princeton who took charge of the label in 1990, Homestead just couldn’t compete.

“We never had anywhere near the kind of resources available for promotion that the other labels did,” says Katkin. “Sub Pop was borrowing a lot of money and promoting their stuff heavily. They were actually on the verge of bankruptcy when their ship came in with Nirvana. With Homestead, that was never an option; we always did things as low-budget as possible. So we weren’t poised to market to the mainstream.”

Even if Homestead never cashed in on grunge, Katkin’s era produced respectable records by college-radio favorites Seam, Love Child and the Dentists, as well as seven-inches by Tsunami and Bratmobile. Katkin also proudly notes that he helped convince Sebadoh to go electric, and he urged the band to release the seminal “Gimme Indie Rock” as a single. But one of Katkin’s reasons for aiming low with his roster, commercially speaking, had little to do with the alt-rock atmosphere: He was simply wary of Tenenbaum’s business practices.

“Because I already knew the operation was something of a criminal enterprise and was not going to really pay any artists no matter what they sold, that influenced my A&R decisions,” says Katkin. “I started to see my mission as trying to put out records that had a lot of artistic merit and weren’t likely to be huge sellers. I didn’t want to be in a situation where a band sold 50,000 copies and then got ripped off.”

Sales figures of Homestead releases around this time more typically ranged from a few hundred to a few thousand. According to Katkin, Tenenbaum cut no royalty checks to artists during his two years at the label and often neglected to provide bands with biannual accounting statements. MAGNET spoke to more than a dozen former Homestead artists for this article. Some are still seeking financial compensation; some make no claims against Homestead or Tenenbaum. Others, such as My Dad Is Dead’s Mark Edwards, say they naively signed a contract and will probably never know for sure if they’re owed money. But a 1992 attempt to piggyback the grunge boom is indicative of Homestead’s shrewdness.

“When the whole Seattle thing exploded, Homestead released the Green River record on CD with big stickers saying ‘Members Of Pearl Jam And Mudhoney,’” says Arm. “They paid us some money up front, maybe $1,000 or something, but we never got a royalty statement after that. I remember Steve (Turner, guitarist) would call them up laughing and say, ‘You guys are pigs. Pay us money.’”

Time and again, Katkin found himself in the uncomfortable position of being unable to address artists’ inquiries about royalties and other financial matters. He left Homestead in ’92 under unpleasant conditions.

“The last time I saw Barry was in court,” says Katkin. “I sued him, because he gypped me out of my last paycheck. I took him to small-claims court in Nassau County, and he showed up and actually tried to argue that he didn’t have to pay me my last paycheck.”

Katkin, who went on to attend law school and now teaches at Northern Kentucky University, won the case.

“We came in at the decline,” says Peyton Pinkerton, singer/guitarist for New Radiant Storm King. “I was such a huge Homestead fan. We couldn’t think of anything cooler. We turned down a couple major-label deals to sign with them.”

In the spring of ’93, Pinkerton says it wasn’t unusual to see A&R men from Warner Bros. or Sire hanging around dive clubs, searching for the next hotly tipped indie band. But for the idealistic members of NRSK (then students at Hampshire College in Northampton, Mass.), indie cred trumped major-label advances. While the buzzed-about NRSK was poised to be Homestead’s hallmark band, Pinkerton’s opinion of the label—and Tenenbaum—quickly turned sour.

“During a Christmas break when I was home from college, I needed some work, so Camille (Sciara, Dutch East employee) hired me to help in the warehouse. She had to argue to get Barry to give me minimum wage. It was a giant warehouse, and things would get damaged every once in a while—cassettes with cracked cases or whatever. Camille said, ‘Take whatever you want from the broken section.’ I remember leaving at the end of the first day and walking up to Barry’s office to thank him for the job. Barry saw a cassette in my pocket and demanded that I empty all my pockets and accused me of stealing. Fortunately, Camille came in and rescued me. But Barry took a dollar out of my paycheck for every broken cassette I had.”

“That doesn’t surprise me at all,” says Katkin of Pinkerton’s story. “But there was a warehouse manager who did steal a lot, so that wasn’t total paranoia. He had a key, so he’d come in when the place was closed and take out cars full of stuff. After he was fired, Barry would check [the warehouse workers] on the way in and take their coats so they couldn’t stuff things in their pockets.”

In fall 1992, Steven Joerg—formerly employed at Bar/None Records—took over as Homestead’s manager. While he continued the label’s hipster-rock trajectory (Soul-Junk, Sleepyhead, Antietam), Joerg adopted a radically different vision for the label after signing avant-garde jazz saxophonist David S. Ware’s quartet in 1995.

“I became rapidly aware of a whole other underground when I began working with jazz artists,” says Joerg. “So many modern musical masters were not being recorded and represented in the music marketplace. I was deeply inspired to change that.”

“[Joerg] had a vision of Homestead coming back as a label with some integrity that wasn’t just indie rock,” says Pinkerton. “He was trying to bring it into the ’90s. I feel incredibly sad for Steve Joerg. He did the best job he could with one arm tied behind his back.”

Joerg left Homestead at the end of ’96 to start his own jazz-oriented label, AUM Fidelity, which evenly splits profits with its artists. Homestead stopped releasing records (the discography ends with a whimper: Ivo Perelman’s Cama Da Terra), but Dutch East continued to operate as a distributor, selling merchandise to stores until 2002 and last updating its Web site in 2003.

The story should end here. But unfinished business affairs—claims of unpaid royalties, disputes over ownership of master tapes—have carried the Homestead saga a decade past its expiration date. Also worthy of discussion is the intrigue of Tenenbaum himself, a shadowy figure whom few artists even set eyes on.

“He was always into secrecy and being low-key,” says Katkin. “The idea of being as anonymous as possible has been with him a long time. If you walked into a 7-Eleven on Long Island, a lot of other people would look like him. He didn’t interact with the people who worked there, and he would never have gone to a club to see a band. He didn’t like to socialize with anyone, as far as I can tell.”

“He looked like nobody,” says Pinkerton. “He looked like Larry David, kind of. Nebbish, slightly balding, glasses. He looked like a Barry. Bad white sneakers and T-shirt tucked into jeans.”

In recent years, Tenenbaum has been a difficult man to locate. He isn’t impossible to find—the recent reissue of Dinosaur Jr’s debut indicates a deal has been struck to purchase ownership of that album—but his reputation for evasiveness has made him into a weirdly mythic figure.

“The only way that you would possibly get in contact with him is to try and release one of the albums that he had a perpetuity contract on,” says Alan Mann, who oversaw Dutch East’s licensing of Peel Sessions in the early ’90s. “Then he’ll come out of hiding and try and sue you, like he did with the label (Drag City) that tried to reissue the Bastro LPs. He’s in hiding, and I doubt he would talk to you even if you tracked him down.”

“I’ve sent certified letters to him,” says Pinkerton, who last requested accounting statements from Tenenbaum in 2000. “Apparently, he’s got some Chinese wall around him and cannot be contacted.”

Finding Tenenbaum, it turns out, is only part of the puzzle. Finding the assets of Dutch East—its accounting records, legal contracts and a warehouse full of merchandise—completes the picture.

On a tip from Katkin, MAGNET looked up eBay seller “lunapark010,” the I.D. used by former Dutch East sales manager Jack Sheehy. An eBay “power seller” with more than 6,000 transactions, Sheehy also maintains his own eBay store that auctions CDs, vinyl, T-shirts and other music-related merchandise. By scanning the list of items for sale—albums by Homestead acts Brainiac, Big Dipper, Daniel Johnston and Dinosaur (a first pressing, before the “Jr” was added)—along with such information as a post-office box in Kingston, N.Y., and a non-functioning contact e-mail address (jack@dutch-east.com), it’s reasonable to surmise that the contents of the Dutch East warehouse are currently for sale on eBay.

MAGNET’s e-mails to Sheehy via eBay went unanswered. But his auction page yielded one more clue: a curious link to a site that sells merchandise from the Iron Chef TV series. A previous Google search of “Barry Tenenbaum” had turned up a 2002 License magazine article mentioning someone of that name securing the rights to U.S. distribution of Iron Chef cookware, T-shirts, aprons and coffee mugs for a company called ET Ventures Ltd.

“ET is Barry’s father, who used to work [at Dutch East],” says Katkin when asked about the company name. “His first name was [Edgar], but he preferred to be called ET.”

The connection between Tenenbaum and Sheehy seems clear, and an e-mail to the Iron Chef merchandise site, requesting an interview with Tenenbaum, was promptly answered. Broaching the topic of royalties, MAGNET inquired whether Tenenbaum owes money to Homestead acts.

“Lots of royalties were paid, but it’s unlikely that more than one or two releases after HMS125 (Giant Sand’s 1988 album The Love Songs) or so ever earned back their advances,” he writes.

When asked about the current status of Dutch East, Tenenbaum’s reply is cryptic.

“Basically, when music became free on the Internet and (with) so many labels selling direct to our accounts all over the world, it became a very difficult environment starting in the late 1990s. Then all of our big accounts started going bankrupt and Dutch East lost everything. It’s not dormant, just gone. Homestead is technically in a very complicated legal situation and will remain so for a long time.”

“What he’s calling ‘complicated’ is just simply that he’s a criminal,” says Katkin. “He had a warehouse full of records on consignment, and … one day took off with all that stuff. That’s what’s complicated. He can’t be found because he didn’t declare bankruptcy. He simply stole all the stuff he had in the warehouse and absconded out of paying royalties to the bands and made himself disappear.”

Further e-mails to Tenenbaum—concerning his whereabouts and the details of his eBay endeavor with Sheehy—went unanswered. He did, however, take exception to Albini’s assertion that accounting statements were purposefully wrong.

“He is a liar,” writes Tenenbaum of Albini. “As to statements having math errors, (it is) simply not possible. All the statements were generated by a computer program off a database of transactions. Last I checked, none of our computers made consistent math errors. Ever.”

Call it a case of Tenenbaum’s royalties. According to Evan Cohen, head of business affairs at Manifesto Records and an entertainment lawyer who litigated for the Kingsmen in order to win them rights to “Louie, Louie” in 1998, it will be difficult to determine whether bands such as New Radiant Storm King, My Dad Is Dead, Green River and others have a valid claim against Tenenbaum. One glaring problem is the absence of a paper trail—or SoundScan figures, which didn’t begin tracking sales until 1991—that would determine just how many records these bands sold.

“There will be no forensic accounting with regard to record sales in the ’80s,” says Cohen. “It just isn’t going to happen. Plus, there are statute of limitations problems: New York might have a four-year or six-year statute. If [Tenenbaum] didn’t pay you in 1990 and he should have, you had until 1996 to sue him. And that was 10 years ago.”

Cohen offers his services to bring legal action against Tenenbaum—either to reclaim master tapes of out-of-print recordings or collect royalties—provided enough aggrieved artists get together to make the case worthwhile.

“The thing is, none of us are rich,” says Pinkerton. “Anyone who made a lot of money already got their record back or somehow forced it. Everyone is still scared. It’s hard to get these Homestead bands together because of contract disparities, and some people are just plain scared of this guy.”

Albini, who wouldn’t take part in such a lawsuit because Big Black licensed rather than signed to Homestead, is nevertheless annoyed at the sale of Big Black’s music on eBay. “I would love it to stop,” says Albini. “It would cost me too much to stop [Tenenbaum] because I would have to go through a court battle with him. It would be sort of satisfying to see him driven into bankruptcy and then madness and possibly suicide, but I don’t want to participate in it. His sins against my band were a long time ago.”

Not all Homestead alumni feel cheated, however. For Death Of Samantha frontman John Petkovic (currently of Cobra Verde), these issues—Petkovic retrieved his recordings from Homestead more than a decade ago—are moot.

“Trying to put this all together is almost like auditing the irrational,” he says. “Indie rock was never built to make money. This label put out a shitload of records. Some of them were good; a lot of them sucked. At least the records came out. I never even asked for a royalty statement. If you’re angry about Barry Tenenbaum cheating you out of a couple thousand dollars, then you ain’t never gonna have fun in life. If all those bands added up all the money they spent buying bags of potato chips out of vending machines over the years, they’ve spent more than they would’ve gotten in royalties.”

“Perhaps many misunderstandings occurred because I left all label activities—including musical, marketing and dealing with bands—to a middleman (who was) often quite young,” writes Tenenbaum. “It was easier to deflect all blame to the guy not there: me.”

An examination of recording contracts and accounting statements could prove that Tenenbaum is correct, and that many bands never recouped their expenses. If this is the case, there’s nothing unethical about the eBay operation—except, perhaps, that sales aren’t being reported to the bands.

“If [Tenenbaum] doesn’t owe any royalties, then [what’s wrong with] the fact that people didn’t get an accounting that has a bunch of zeros on it?” asks Cohen. “That’s not a really great case.”

Decades-long arguments, missing money, finger-pointing, the harsh realities of the music business—it’s all part of the indie rock Homestead gave you. Pinkerton, who’s recently toured as a member of the Pernice Brothers and Silver Jews, describes a “knowing look” of disgruntlement that’s still exchanged between former Homestead artists whenever their paths cross.

“I’ve had my ups and downs in the music business and I try not to be a grudge holder, but I would have to say Barry Tenenbaum is the one person I would say is unconscionably evil,” says Pinkerton. “Actually, that’s giving him too much power. He’s the one person I’d disparage in an interview without a caveat or disclaimer.”

Only time—and, most likely, a lawsuit or two—will decide the outcome of decade-old grievances. What remains untarnished is Homestead’s legacy of adventurous albums and old-school, DIY camaraderie.

“When I think about Homestead, I think about what a cool community of bands we had,” says Great Plains’ Wyatt. “I put lots of them up at my house when they toured through Ohio in the ’80s and got to be friends with most of them. Dinosaur weren’t even fighting with each other at that early point … Homestead keeps coming off like a label that’s inept at best and corrupt at worst. That wasn’t my experience. To me, they were a label that championed mostly unpopular stuff. They ought to get their due for that now.”

4 replies on “Homestead Records: Frontier Days”

[…] struggle getting paid and all sorts of shenanagans went on which is well detailed in this excellent Homestead history over here if you want to read […]

[…] Albini, Magnet, 2006. On notorious indie imprint (and one of Sonic Youth’s first labels) Homestead Records, run by […]

[…] Homestead title; the label’s manager, Steven Joerg, soon left to form AUM Fidelity. This superb Magnet article tells the label’s whole story, good, bad and ugly.) I remember very little […]

Wind-up Records label which is Evanescence label is a sub of Dutch East India Trading which dates back to LSR and Homestead. The band which I named Evanescence in 1983 after being discovered my Joe Elliott of Def Leppard and an unknown Kurt Cobain I was writings for at the age of 15. Evanescence, Kurt Cobain and Nirvana not only have the title to a song in common (Lithium), but me. I am the real Amy Lee and the lead singer uses my name as her stage name.