The Making Of …And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead’s Source Tags & Codes

By Kevin Stewart-Panko

“We toured with the Foo Fighters, and their road crew hated us,” says Jason Reece. “I mean, the band liked us, but their crew fucking hated us!”

If ever we were challenged to write a super-condensed history of …And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead, that might be it. Well, that could be it, but it definitely wouldn’t tell you anywhere near the whole story. Its artistic kitchen sink and devotion to heartfelt expression—delivered via a seemingly endless array of hooks—appeals to factions of both the underground and mainstream, but the band’s sound and antics also possess enough abrasive danger to scare the genteel away, if not piss them off entirely.

Why did the Foos’ crew despise these guys so much? Well, as anyone who’d witnessed the Austin band live from its inception in 1994 could tell you, the conclusion of its gigs was usually signified by a wholesale instrument trashing. Grohl and Co.’s handlers probably got sick of ducking drum shards and flying guitar necks, not to mention being on residual clean-up duty, having to reposition mics and monitors, let alone watching the violent nightly death of instruments, as Trail Of Dead used this extreme measure to signal that there would be no encore—and for dumbasses to stop yelling, “One more!”

“Exactly,” laughs Reece, who has comprised the band’s core since day one, along with fellow multi-instrumentalist Conrad Keely. “I have no clue, dude,” he continues, when asked for a ballpark figure on the destruction, “but it’s definitely a lot of money we probably could’ve saved. I mean, we invested in cheap instruments, but that doesn’t matter—they still cost money. We did that from the start, though; it was second nature to trash the motherfucker, and that was the way to end the show. It was fun, but after a while it became a little contrived, no matter how much money we had. Some people got it; other people were like, ‘Oh my god, what is this?! What does this mean?’”

“I’d rather not speculate,” says Keely, “but I will say that the money matters less to me than some of the beautiful guitars and drums we sacrificed in the name of the theater of spectacle.”

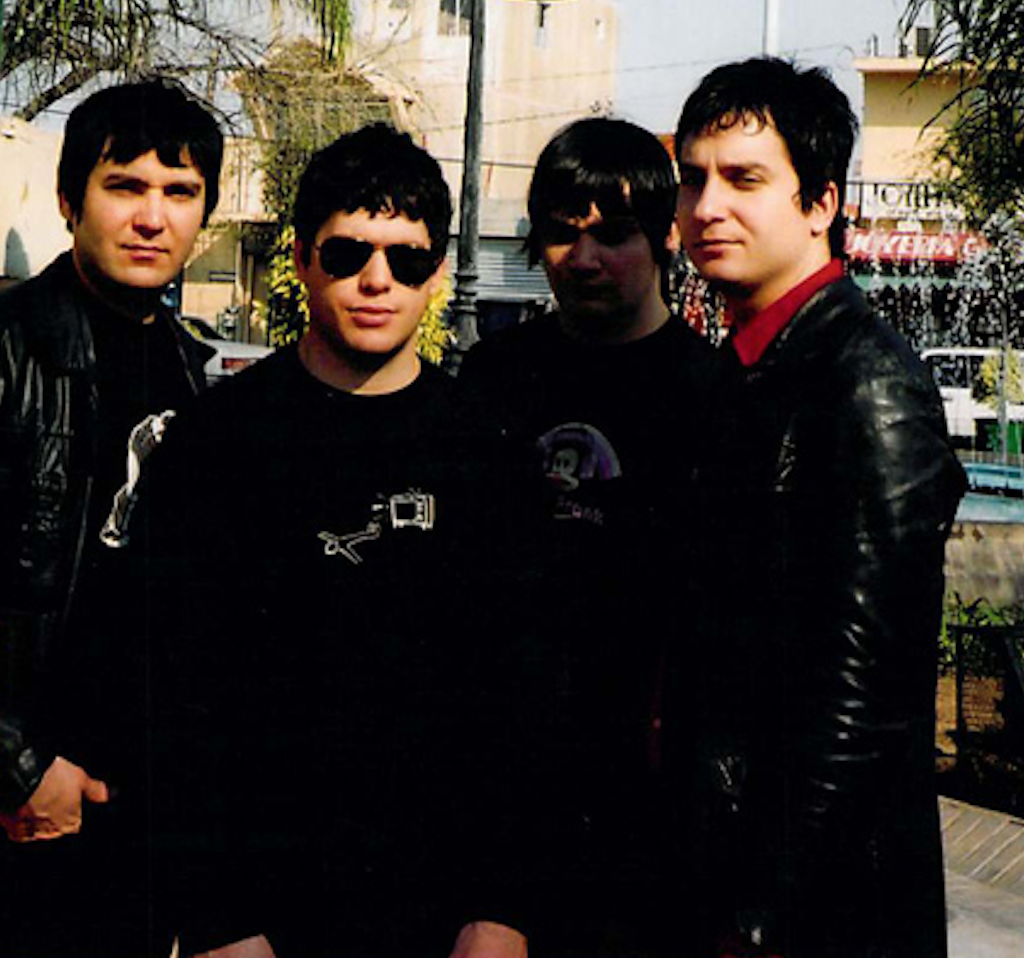

Ah, money. Cash. Greenbacks. Benjamins. The root of all evil. That which we wish would grow on fucking trees. The only thing we both love and hate more than our significant others. The period leading up to the 2002 release of Trail Of Dead’s third album, Source Tags & Codes (considered by fans and critics to be one of post-hardcore/prog-punk/alt-math/indie rock’s definitive and enduring works) was a period of musical and lifestyle transition for Keely, Reece and former members Neil Busch (bass, vocals) and Kevin Allen (guitar).

The band was buoyed by the business and infrastructure being built around it, not to mention an uptick in its bottom line. Having gained traction in Europe in the early 2000s, the group found itself experiencing a different series of highways, byways and service-station delicacies before returning to Austin and finding the veil lifted on its local and industry obscurity. Gone were the days of sneaking into studios during off-hours, as the band did in order to record its first two albums, 1998’s self-titled debut and 1999’s Madonna. A&R types with expense accounts started poking around, and major-label offers were entertained and weighed before Trail Of Dead eventually signed Interscope’s dotted line.

“I think we were really excited about being in a band,” says Reece. “And the fact that we’d started to tour around Europe and suddenly had Interscope willing to give us a budget to record. There was a little bit of that major-label pressure—the corporate ogre we’d always despised—but at the same time, we were very aware of what we wanted. We had songs and an idea of the direction, so the mood was very full of wonder, upbeat and positive.”

“It was an optimistic time to be living in Austin, a great music community,” says Keely from his present-day home in Cambodia. “Our goal was to break the ‘curse.’ People used to say bands from Austin got stuck there, that they never went anywhere, just ended up playing local clubs and never going international, let alone national. We wanted to make sure that didn’t happen. We were never in any doldrums after Madonna. We were extremely active because we had started to tour Europe and everything was looking up. If anything, I was looking forward to some time at home writing. After we signed to Interscope, I took a job at a record store. It was the first job I did that wasn’t for the money—as was clear to my bosses because I usually didn’t bother picking up my paychecks—but to do something: mainly, listen to new music. It was an experimental record store called 33 Degrees, so the selection was eclectic, and it was where I heard a lot of weird new stuff for the first time—stuff way outside the rock genre.”

“We were just rolling off of one album into the next,” says Reece. “We were dealing with the constant European touring for Madonna and coming back and working day jobs, so I think we were all about just getting the new thing going. And the label wasn’t telling us what to do, so we were generally motivated.”

Trail Of Dead was spreading its wings. Not content to remain static, Source Tags & Codes was the synthesis of the caustic fire that powered its early albums with the discovery of a broader world of sound. Additionally, Source Tags was the band’s conscious attempt at shining a little literary light onto the alternative nation’s insular worldview, creating an album that flowed with intent, purpose and in a definite direction. You can hear it from the start, as opener “It Was There That I Saw You” injects melancholy melody into a sonic flare of raging post-hardcore before the fury takes more pensive and spacious turns with “Another Morning Stoner,” “Baudelaire” and the tumultuous ebb and flow of “Homage.” Separating those tracks are ambient soundscapes, effects and cabaret noises. As the irascibility simmers on “How Near, How Far,” the string arrangements start their gradual ascent, first as connective tissue during the song’s jangly middle-eight before playing a more pronounced role in the crescendo of “Monsoon” and alongside the sparse piano sequences of “Heart In The Hand Of The Matter.”

“A lot of it was written in Austin, hanging out and doing it how we would normally do—getting together three or four times a week and just playing for hours,” says Reece. “In the end, we were thinking about it as an album that you’d put on and listen to all at once. To make it a journey—not just a collection of songs—was our goal. The other thing was to make the lyrics as meaningful to us as possible. We were into some very literary figures and aspiring to be little beat poets, which might sound cheesy, but we were into Bukowski, Henry Miller, William Burroughs and sci-fi. We were into books and trying to be deeper lyrically and paint pictures and tell stories like Patti Smith, Beck, Springsteen, John Doe and Exene Cervenka would.”

“We were getting into a point where the stress of touring together made it difficult to meet and write as a group,” says Keely, with different memories. “We tended to fade into our own lives when we got home. So, I did most of my writing by myself at my house. Then, we got together and hashed out arrangements. Jason and I were still great at working together, but sometimes the effort of pleasing a group of four made it difficult for us to reestablish that ease of writing that inspired our earlier material. So, in many ways, the material on Source Tags was a lot more laboriously written, and in some ways even more contrived, though not for the sake of any audience so much as for the sake of making it work as a four-piece band operating under a philosophy of solidarity.”

Capturing the songs on tape was another labyrinthine process due in large part to the monetary freedoms afforded the band. “It was the first time we had a budget and could afford to be a little frivolous, even though I don’t think we were frivolous,” says Reece. A total of six studios were used across the country, from Brooklyn Bridge in Austin to Prairie Sun in Cotati, Calif., where the lion’s share of the album was laid down, and three different studios in “the creative black hole” (as described by Keely) of Nashville before editing and mastering sessions began at Masterdisk in New York City.

“We were going to record at Electric Audio, but Steve Albini was booked up and told us to go to Prairie Sun, actually,” says Reece. “We started in Austin, then we went up to Cotati, which is 50 miles north of San Francisco in the middle of nowhere. We were recording at this place that was like a chicken ranch. We were there for a whole month, and a lot of writing was done there. We were really picky about what we were doing, too. We didn’t want it to be an average third album, but it was a little bit like The Shining. It was easy to lose your mind up there. (Producer) Mike McCarthy was sort of like our mentor and dad at the time, but he started regressing just like we were. There was definitely a little bit of that ‘losing it’ feeling. It wasn’t like we were doing drugs or anything; it was that we were so self-contained and so in our own head space that we were driving each other crazy. There was absolutely nothing to do there unless you wanted to go into town and hang out with a bunch of Hells Angels and hippie burnouts.

“We went to Nashville to mix and finish up. That boiled down to Mike having grown up recording in Nashville; he got his education recording country music. He really fucking hated it, but he kept a good relationship with a lot of the people he worked with. He would be like, ‘I fucking hate this place, but the equipment they have is amazing!’ He got us into Oceanway, which is a very cool studio in an old church and a completely luxurious place where huge country stars record. That’s where we recorded a lot of the string arrangements and orchestral parts.

“The funny thing was we were upstairs and the Cash Money dudes and Juvenile, the rapper who did ‘Back That Azz Up,’ were downstairs. We would all hang out in this one common area. There was this strange meshing of worlds of these New Orleans rappers and us Austin rock dudes, and they were like, ‘Do you want to do a collaboration?’ We were like, ‘Ah … um … erm, no. Sorry!’ and later just laughing at the idea of what that might possibly sound like. But we smoked a bunch of weed with them, hung out and checked out each other’s music. They were like, ‘What the hell is this? What are you guys on?’ They had never heard anything like it.”

Upon its release, Source Tags & Codes was an instant hit. Pitchfork bestowed a rare 10/10 upon it (“At first, we were like, ‘What is this Pitchfork?’” says Reece, “but I remember Radiohead and Wilco getting 10s as well, so we were like, ‘Does this mean we’re OK?’”) as longtime fans cottoned onto the band, blowing open the doors. As well, those previously unaware of the Trail Of Dead cult found themselves drawn in by the excellent songs, moody rollercoaster, bald emotion and Interscope’s promotional budget. Things exploded as the band hit the Billboard charts to the tune of 65,000 copies sold in the U.S. in less than six months, before hitting the road for nigh on three years.

“I’d say we toured it a year longer than we should have,” says Keely ruefully. “But at the time it was easier to stay on tour than it was to face the thought of returning to the studio to write another record. That goes to show how people can change over the years, because these days I feel almost the exact opposite.”

On the topic of change, with MAGNET doing these intensive look-backs at particular eras and albums, we’d be remiss if we didn’t ask if there was anything the band would change about Source Tags or do differently during that phase of Trail Of Dead’s existence. (The band’s lineup is now completed by Autry Fulbright II and Jamie Miller, who are now working on the follow up to 2012’s Lost Songs.) Especially with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight and the consideration that songwriters are always their own worst critics.

“Not really—it’s our history, something we went through,” says Reece. “There are always things you wish you did looking back, being older and more mature, but you have to go through all the scrapes, learning lessons and getting burned to evolve. So, there’s not much to do other than realize that’s what happened and that’s what it is. We were out touring a couple months ago, doing Source Tags in its entirety, and the music still flows, and that’s remarkable to me, whereas we did Madonna for a Japanese tour and it seemed disjointed. Source Tags’ sequence made sense from start to finish, and it still sounded relevant. I don’t know if that’s me kidding myself, because you always want things to be timeless, but it seemed like the material still seemed inspired, and that’s a beauty and a curse.”

“I would have started work on the next album sooner,” says Keely, gravitating to what might have been. “I would have tried to be a better person—a better leader, follower, listener and friend. I would have taken better care of myself and my bandmates on tour, turned down more free dinners, put some money away for rainy days. But there is no advantage to this sort of thinking. We make our mistakes and learn from them, and with any luck we move on.”