The making of the Lilys’ The 3 Way

By Matthew Fritch

“The 3 Way is the result of my longstanding infatuation with the natural world as experienced through mathematics and technology and how a lot of science became science fiction starting with, of course, Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash. The ideas in The 3 Way were laid out in the diamond age, about working in carbon, basically assembling our new nature out of carbon. At the low information level, what would someone who could be anything be? They make themselves these horrible, musclebound monsters. It’s kind of cute. Those who seek to modify themselves the most have the most to learn, basically. I’m glad I got that off my chest.”

That’s Kurt Heasley, the six-foot-six staggering genius songwriter of Lilys, describing his band’s 1999 album The 3 Way before even being asked a question about it. Heasley tends to talk about five things at once, a character trait that extends to the circuitous, complex songs he’s written and recorded with a dizzying array of lineups. (At last count, approximately 50 musicians have been in Lilys since the group’s inception in 1992.) Although Heasley can scatterbomb an hours-long interview with rambling asides on the Illuminati and madcap laughs about the follies of modern living, it would be foolish to underestimate him. Just when the thread of conversation seems hopelessly lost, he snaps back into focus.

“Did you want me to tell you about the harpsichord?” Heasley asks. “Because we can talk about the harpsichord. I’m just painting the corners of the canvas.”

The 3 Way does, in fact, feature a harpsichord as one element in its impressive, photorealistic rendering of vintage 1960s mod rock and buttoned-up orchestral pop. Along with Lilys’ 1996 LP Better Can’t Make Your Life Better, it represented a stylistic turn from the band’s early, shoegaze-inspired sound. Heasley says that he grew up with a deep love for the Monkees and Peter, Paul And Mary, but his affection for 1960s pop really blossomed in the summer of 1995. He was living in a house in Denver with the members of the Apples In Stereo, a band obsessed with the Beatles and the Beach Boys and on the verge of unleashing a new wave of psychedelia via its Elephant 6 recording collective.

One afternoon, Heasley sat in the basement strumming the songs that would later appear on Better Can’t Make Your Life Better. Up to that point, Lilys songs mostly used a non-standard guitar tuning that characterized their gauzy-sounding early material. When Apples drummer Hilarie Sidney joined Heasley and began whipping out Heasley’s guitar chords in standard tuning, something strange happened.

“I was like, ‘What are you doing?’” recalls Heasley. “And she says, ‘Isn’t that how it goes?’ And I’m melting. I was in awe. I realized (my songs) sound like Pete Townshend. ‘This sounds like Dave Davies. Wow, I’m so close.’”

Following the critical success of Better Can’t Make Your Life Better, Lilys wound up on Sire Records. (“We were not signed,” protests Heasley. “We were induced.”) Lilys’ European label, Ché, had a licensing agreement with Warner Music Group, under the terms of which Lilys albums were released in the U.S. on a subsidiary label called Primary Recordings. When Ché folded, Warner (and, by extension, its subsidiary Sire) had the first right of refusal for the album remaining on the Lilys’ contract.

Nevertheless, moving to a major label was an opportunity for Heasley and the same core group of musicians that made Better: drummer Aaron Sperske, guitarist Torben Pastore and producer/arranger/keyboardist Michael Deming. The band seemingly had a champion in Seymour Stein, the record executive celebrated for having signed the Ramones, Talking Heads and the Pretenders in the original punk/new-wave era. More important, there was a recording budget—Sperske estimates it was $150,000—that was far more generous than anything Lilys had been afforded before. Sire suggested a few different producers (Heasley declined to identify them), but Heasley was clear in his desire to again work with Deming, whom he calls an “arranging composition powerhouse.”

In late October 1997, Deming was concluding production work on the Pernice Brothers’ debut, Overcome By Happiness, at Studio .45 in Hartford, Conn.—so named because the building had been the site of a Colt firearms factory. Exactly one day after finishing the Pernice Brothers album, Deming began recording The 3 Way. (Remarkably, drummer Sperske was also a holdover from the Pernice Brothers sessions.) For Deming, who studied music theory and composition, business was booming in the late ’90s. Artists such as Belle & Sebastian and Elliott Smith had revived a niche of delicate chamber pop of the late ’60s; cravat-wearing groups like the Left Banke and the Zombies were suddenly in vogue again among a certain population of listeners. And with that renewed interest in string sections and arrangements, Deming’s talents were in high demand.

“If you don’t know how to write and conduct a string quartet, you shouldn’t be trying to mess with them,” says Heasley. “I didn’t want to stop the world for seven years and get those skills under my fingers. I had to trust someone who had, and Michael Deming had an absolute sense of adventure and tonality.”

The winter of 1997-98 saw Heasley (guitars), Sperske (drums) and Deming (keyboards and production) hunkered down in Hartford, making steady progress on The 3 Way. The ambition of creating an orchestral-pop album cut both ways: It was an admirable goal, but the structured, George Martin-esque approach was far different from the fast, loose and spontaneous process that Lilys were accustomed to.

“When we did Better, there was a lot of intuition involved, and it was more like splatter art,” says Sperske. “You would run out and do something sloppy and cool and not perfectionist. The ideas were going at a very fast clip, and that album was done beginning to end in three weeks.”

“I was looking forward to creating something that had the feel of this awesome session album,” says Heasley. “Like, ‘Featuring members of the Turtles!’ But we were basically this rolling art prank, more situationist and stuntmen than music industry careerists. How do you put these components together to make a working record?”

“Deming was great at thinking of some odd instrument that only two people in America could play, and fly one in,” says Sperske. “He was full of that kind of shit. It seemed like we had a lot of resources, so Deming became obsessed with hiring proper union players. It was no longer acceptable for me to play some percussion instrument half-assed if they could go get a real tabla player. Everything became so orchestral. There was this obsession with orchestral perfectionism. We went from being intrepid, DIY psychedelic troubadours to stuffy lab-coat technicians, as if it were EMI studios in the ’60s and everything had to be done just so.”

If the recordings were going to be tightly controlled and precise, Heasley’s songwriting tilted the other way. The 3 Way is a mercurial distillation of ideas, words and styles that form a kind of musical abstract expressionism. There is little adherence to verse/chorus/verse structure; two songs are seven minutes long and one is a short jazz excursion with a spoken-word vocal in Spanish. Melodies whip around cryptic lyrics that only Heasley could hope to explain. Not that it would do you any good: What to make of a song, “Leo Ryan (Our Pharoah’s Slave),” whose closest thing to a chorus is “I am Pharoah/You work, I eat” and seems to describe a dystopian reality involving a U.S. congressman assassinated in Jonestown in 1973?

“Kurt is one of the best stream-of-consciousness songwriters I’ve ever worked with,” says Deming. “He doesn’t write a song in a conventional sense, and it made it so interesting. His way of composing opened up so many possibilities.”

“Most of the songs on The 3 Way existed on cocktail napkins and journals and notebooks, something like 2,000 or 3,000 words that I had to select from as we were recording,” says Heasley. “It was culling thousands of words into hundreds of words into a chorus.”

Likewise, the panoply of musical influences seemed filtered through decades of recorded material. Heasley’s sing-song vocals naturally recall the pliable melodies of the Kinks, but bandmates cite various and conflicting sources of inspiration while Heasley was living in Hartford with his wife and baby daughter around this time.

“Kurt is very much a sponge of his environment, musically speaking,” says Sperske. “So all the music they listened to was this old Hartford AM radio station that played ’50s and ’60s hits, many of which were regional. I could tell that a lot of songs, like ‘Dimes Make Dollars,’ had been ripped from that oldies radio.”

“We were listening to James Brown and Philly soul in the studio,” says Pastore. “I was listening to the Fall a lot. I went to a Bo Diddley concert one night and called up Kurt from a phone booth afterward and told him we gotta do something like (the guitar riff from ‘Dimes Make Dollars’). And he did it. What we were not listening to and not thinking about was the Kinks.”

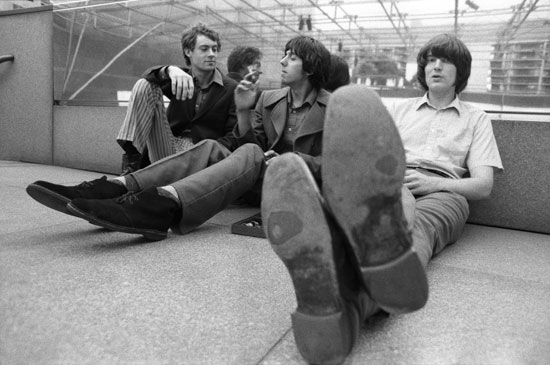

A few months into Lilys’ recording of their anachronistic pantomime of a British Invasion band, they actually got big in Britain. Thanks to a Roman Coppola-directed Levi’s jeans ad that aired in the U.K. and featured Better Can’t Make Your Life Better track “A Nanny In Manhattan,” the group suddenly had a top-20 hit in England. Lilys flew over to perform on Top Of The Pops in February 1998, with Heasley sporting a Beatle bob and mugging for the camera like the fifth Monkee. What seemed like another golden opportunity for exposure, however, quickly soured as the television appearance only seemed to slow the momentum on The 3 Way and intensify the shortcomings of the band’s publishing and recording arrangements.

“‘A Nanny In Manhattan’ was great for the people who owned the sound recordings and the publishing, but it didn’t do us a lick of good,” says Heasley. “It paid a half month’s rent to go over and do Top Of The Pops. When it feels like the world is awash in money … I don’t think Top Of The Pops was a healthy decision for us.”

The 3 Way became further delayed when it was decided that in the wake of the Levi’s ad, Better Can’t Make Your Life Better should be remixed and reissued with orchestration taking the place of the synthesizer sounds on the original recording. Deming was enthused about replacing the synths—which he considered placeholders—with a string section; Sperske and Pastore thought the remixes were overwrought and pointless. The band was also sidetracked into making a six-song EP titled Services (For The Soon To Be Departed), which had the effect of convincing Sire that Heasley was a hyper-creative fountain of songs. Such a prolific songwriter, they reasoned, hardly needed to be checked on or monitored as The 3 Way progressed. In reality, however, Heasley and Sire seldom understood each other. The two were at bitter—or worse, indifferent—odds.

“I understood what everyone from Steve Albini to Ian MacKaye to Dave Grohl had warned about: Be careful what you sign,” says Heasley. “Make sure if your understanding of how you work is not reflected in the contract, don’t sign it. Between 1997 and 1998, for 10 months I did everything I could to bring as much of our needs to the table to create a 12-month plan that included recording and live performance and living needs and trying to anticipate … it didn’t work very well.”

Of course, Lilys were bedeviled by a common plague among indie bands considering themselves artists first and entertainers a distant second: the lack of professional management and representation.

“I desperately campaigned for us to have a manager for years,” says Pastore. “It was a terrible waste of Kurt’s talent to manage us. He was terrible at it. He has the wrong psyche for it. Ninety percent of the problems he had was because he was not cut out for it.”

Not even a manager could have sorted out the complex cultural forces that made Lilys outsider artists on their own record label. When discussing the prevailing mood of the music industry at the time, each of the three full-time members of Lilys independently mentions Aphex Twin. For Heasley, the surging popularity of techno music was inspiration—he later made an electronic/krautrock album, Zero Population Growth, under the Lilys name. For the other band members, it was an ominous sign of the times—specifically, the disturbing image of Richard James’ bearded face superimposed on a bikini-clad body in Aphex Twin’s “Come To Daddy” video.

“We realized the market had moved onto electronica during the time we were making this record,” says Pastore. “Seymour Stein no longer had any power in Warner Bros., so it would be best to take whatever they owed us as a writeoff, and use that to support the Aphex Twin video. That was the explanation two different people at the label gave me.”

Sperske says that Stein was embroiled in a power struggle with Sylvia Rhone, then head of another Warner property, Elektra Records. (Around this time, Rhone was excoriated in song by Elektra castoffs Spoon, whose “The Agony Of Lafitte” mentions her by name.) The Sire label was resurrected by Stein to suit his rock ’n’ roll tastes.

“Sylvia only wanted hip hop on Elektra,” says Sperske. “Our rock band was not in vogue in that era, so Seymour started Sire.”

Despite his curiosity toward electronica, Heasley reveled in the Lilys’ counter-revolutionary stand against modern digital recording, lo-fi bedroom indie rock and whatever else was fashionable to consume at the time.

“What would be the ultimate robot revolt in the late ’90s?” he asks. “It would be to not do electronic music or this heavy, detuned, distortion sound. We’re going to do the exact opposite and point out this other reality thread.”

And this is where the harpsichord comes in. It turns out that Deming had, in high school, participated in and won an instrumental competition in New York City using a 1930s Neupert harpsichord made in Bamberg, Germany. During the recording of The 3 Way, Deming secured that same harpsichord from his high school and used it on several tracks. The harpsichord was so difficult to keep in tune, he kept the tuning pegs inserted and stopped every couple of measures to re-calibrate the instrument. If there is a metaphor for the out-of-time, traditionalist nature of The 3 Way, it is the 1930s Neupert harpsichord.

Deming describes the late ’90s as “the zenith of analog recording.” Manufacturers such as M3 had perfected the chemistry of making tapes that minimized hiss and distortion; at the same time, digital technology had progressed beyond cheesy-sounding, ’80s-era techniques to allow for optimal integration with recording to two-inch analog tape. This confluence was a boon to audiophiles like Deming, who was not going to waste an opportunity to create the best-sounding recording that time and money would allow.

“The beauty and the curse of The 3 Way is that it’s perfectly done,” says Pastore, now a hearing scientist trained in architectural acoustics. “Deming was very clear about what he wanted and stuck to it. It’s not like he tricked anybody. There was a little power struggle between him and Kurt, but they were also having a lot of fun. It was a meticulously done record—perfectly recorded in an analog sense.”

Neither Deming nor Heasley recall a particularly contentious relationship over the direction of the album. Heasley did imagine that The 3 Way would be a weirder affair—something more akin to the Walker Brothers’ dark, spartan Nite Flights—though he seems equally enthralled with Deming’s orchestral arrangements. But the pursuit of perfection—along with a host of other factors that included cabin fever, separation from loved ones, record-label strife and indulging in controlled substances—took a toll as the recording, though interrupted by the trip to England and other pursuits, stretched on for nearly a year.

“I was attempting to direct far out of my league, and by the time we had begun tracking guitar and drums, there were a lot of people concerned for their financial and physical well-being,” says Heasley. “Even though contractually we had reached a point where we had come up with a safety plan and an exit strategy, just being involved with an organization like Warner Bros. was enough to unnerve everybody so that the layer of confident abandon wasn’t there. Everything needed to be right. And if everything needs to be right, it’s really difficult.”

“A lot of parts were tracked hundreds of times before Deming was satisfied that they were perfectly played,” says Pastore. “I was in the room when we were tracking the guitar outro for ‘Socs Hip’—I watched Kurt play that for three hours straight.”

Sperske, in particular, felt the strain of living and working in the studio for months, all while being apart from his wife. She eventually flew east to be in the studio and help Sperske cope through the rest of the recording.

“It got to the point where I really wanted to kill (Deming),” says Sperske. “I was plotting his death at night. I was losing my mind.”

“I don’t recall that it was excessive,” says Deming of the work in the studio. “My style is to get it in time and in tune. I might’ve gotten a lot of takes to edit the good stuff together, but I never thought letting it out sloppy would be a good representation of those guys’ talents. I’m a little surprised that after 20 years … It comes with Aaron. That’s all I can say. He did a really great job on that album.”

Along with the work-related issues that surfaced in the studio, rifts began to form among the band members. Sperske says Heasley let the attention and accolades from the press go to his head; days when Heasley’s voice felt the slightest bit weary were spent relaxing in Russian baths instead of the studio, further delaying the album’s completion. Long-simmering suspicions about finances began to spoil relationships.

“Kurt figured out a way to cut everyone off and be the only contracted member and keep the lion’s share of the money,” says Sperske. “I never saw a penny from my work with the Lilys.”

“There was always this thing of, ‘I wonder if Kurt got a bunch of money,’” says Heasley. “Look at the microphone. Look at the studio time. If you want to know where the money is, you’re standing in the middle of it. I respect your reptilian curiosity that I have a goat that I’m gonna go feast on when I’m not eating my rice and beans, but no, I was trying to make a million dollars out of not a million dollars.”

By the time The 3 Way trickled out to the public on April 20, 1999, this particular lineup of Lilys had broken up.

“It was more like a falling apart,” says Sperske, who moved back to California and eventually joined the psychedelic country-rock band Beachwood Sparks. A short West Coast tour featured a version of Lilys essentially playing with Beachwood Sparks as backing band, a stylistic clash that illustrated the divide between Heasley and Sperske. The end of the relationship between Lilys and Sire was messy and complicated. Heasley talks about the separation in terms of escaping through a trap door and severing ties with a large, malicious corporation. Sperske is more pointed in his assessment.

“Kurt called Sire and argued with them and got on their bad side,” says Sperske. “To the point where they were basically like, ‘Fuck you. If you’re going to have this ego trip, then we’re not going to do shit.’ It got to the point where they threatened to shelve the record and not even put it out. They printed up 5,000 CDs of The 3 Way, didn’t bother having it released anywhere else in the world and put those 5,000 copies in their WEA distribution warehouse but didn’t do any radio promotion or posters.”

“The label wanted to make that record disappear,” says Pastore.

“We got a form,” says Heasley. “‘Your contract has been fulfilled.’”

“I don’t think Kurt ever got enough support from any of the labels he was on while I was working with him,” says Deming. “If he would have been given more support, there’s no telling what we could have done.”

Deming still has the tapes from The 3 Way. The label never asked for them. Lilys have continued to make albums (most recently 2006’s Everything Wrong Is Imaginary) and occasionally perform—Heasley lives in Los Angeles with his family and assembled a lineup to play shows in California and New York City earlier this year —but the group never returned to the elegant sound or scope of The 3 Way.

“It’s a beautiful record,” says Pastore. “It was kind of sad. We got a lot of attention from musicians who went on to create bands of their own like of Montreal, the Shins, Apples In Stereo. Somehow we got left out of history completely.”

Quentin Stoltzfus, a close friend of Heasley’s whose star was rising with the band Mazarin just as Lilys were crashing in 1999, has a heavy dose of respect for The 3 Way.

“It is compositionally ambitious, and the sprawling and complex arrangements make it difficult to digest fully,” says Stoltzfus, who now records under the name Light Heat. “The level of detail is purely insane, and keep in mind this was before digital editing became prominent. In many ways, it’s both technically and artistically far superior to anything else that Kurt ever achieved; it’s also an enigmatic totem of the not fully realized potential of one of the great musical minds of our generation.”

Each member of the late-’90s Lilys lineup also laments, in his own way, the wasted potential of that particular group of musicians.

“We were all songwriters,” says Pastore. “This was not a band where one guy is a genius and is teaching everybody else the chords. Everybody on their own was writing 30 songs a year. There were a lot of things we could have done.”

“When I look back at the level of brilliance of everyone’s performance,” says Heasley, “we were making things work energetically. We were rarer elements, and we were a little unstable.”

Recognizing the irony of the album now being inspected and hailed as a classic, he laughs.

Says Heasley, “We’re long-game ninjas.”